See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

From Farm House to Governors Mansion

David Vance was one of the settlers who chose the North Carolina side of the mountains. A veteran of the Continental Army and the Battle of King's Mountain, Vance came to the Reems Creek area of Buncombe County between 1785 and 1790 to work as a teacher, lawyer, and land surveyor. He purchased a farm from William Dever in 1795 that is now maintained as the birthplace of Zebulon Baird Vance, David Vance's grandson and the Civil War governor of North Carolina. The house on the property was built of logs, but it was larger and more elaborate than the typical settler's cabin, for David Vance was more prosperous than the average settler; he was a slaveholder who became first clerk of court for Buncombe County, colonel in the county militia, and representative in the General Assembly. The remote location of Colonel Vance's farm ensure that his family would continue to rely on traditional handicrafts to produce items for daily use in the home and on the farm. Once common in eastern and Piedmont North Carolina, these skills survived in the more recently settled mountains because the difficulty of access kept machine-made products at a distance until relatively late in the twentieth century.

Hope Plantation of Bertie County is a particularly striking example of North Carolina's expanding plantation society. Hope was the home of David Stone (1770-1818), U.S. senator and governor of North Carolina. He was the son of Zedekiah Stone, a Cashie River merchant and planter who had migrated from Massachusetts in 1766. A promising young man with good looks, impressive talents, and valuable connections, David Stone graduated from Princeton with highest honors and read law under his fellow Princetonian William Richardson Davie of Halifax. Before Stone turned twenty, Bertie County freemen had sent him to the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1789. They followed this honor with continuous terms in the North Carolina House of Commons until 1794, when he won election to the bench as a superior court judge. Thereafter, Stone was never absent from public office until he left the U.S. Senate in 1814. Successively he was U.S. congressman, U.S. senator, judge again, governor of the state, member of the legislature, and once more U.S. senator. In spite of this long record of public confidence, Stone resigned from the Senate under fire, when his opposition to the War of 1812 stirred the anger of his North Carolina constituents. When he was only forty-eight, in 1818, Stone died at Rest Dale, his plantation in Wake County.

The self-assurance that stimulated architecture in New Bern and elsewhere and supported the activities of diverse planters like David Stone, Benjamin Williams, James Latta, and Richard Bennehan rested on a growing commercial economy. National independence brought these men closer to the currents of international trade and gave them a personal status that rested on a complex interplay between agricultural production, the demand for staple crops, and world economic conditions.

But what did liberty mean for the independent farmer who tilled the earth with his own hands, lived in a log cabin, and usually avoided stores and merchants as much as possible? According to Thomas Jefferson, these yeomen farmers and their families were the ideal citizens of a republic. "Those who labor in the earth," Jefferson wrote, "are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue and not wealth or aesthetic expression was the supreme test of a republic.

Religion in the Republic

Methodist pioneer Francis Ashbury noted in his journal that the town of New Bern contained a "famous house, said to be designated for the Masonic and theatrical gentlemen," and then noted dryly, "it might make a most excellent church." Aptly called the "Prophet of the Long Road" Ashbury spent almost forty-five years, averaging 6,000 miles a year, traveling and preaching. In 1783 he wrote that "hitherto the Lord has helped me through continual fatigue and rough roads; little rest for man or horse, but souls are perishing -- time is flying -- and eternity comes every hour." Armed with faith that gave them the necessary confidence to distance themselves from the gentlemen of New Bern, Ashbury and his colleagues launched a religious movement that came to dominate North Carolina's popular culture in the century to come.

The crusade was known as the Great Revival. It embraced a variety of churches, individuals, and groups, but the most important denominations involved were the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians. The movement's hallmark was evangelicalism, or an emphasis on personal conversion as the test of Christian salvation. Without an overwhelming personal experience of rebirth, evangelicals held that no amount of good deeds or pious thoughts could justify a person in the sight of God. To the humble individual, the evangelical churches offered a reassurance and a source of personal esteem that did not depend on riches, status, or education. To the collective body of believers, the churches offered a vision of the virtuous republic that did not depend on classical erudition, European nationality, or invidious class distinction.

By 1819 religion had gained great prestige among the gentry according to the grandson of a North Carolina signer of the Declaration of Independence. In a sermon of that year preached to the well-heeled founders of the North Carolina Bible Society, the Reverend William Hooper recalled the days "when religion with downcast eye and timid step never ventured to approach the mansions of the opulent and elite, and only found casual entertainment among the cottages of the poor and ignorant." Hooper rejoiced with his audience that the churches "had grown respectable in the eyes of men" and had won the allegiance of "the men occupying the station and possessing the political influence of those who are now the patrons and pillars of our Bible Society." As North Carolina's commitment to evangelical religion deepened, the churches' style and doctrine became fixed features of the people's common culture. Beginning as a spiritual challenge to the established order, the churches in time became a part of it and gave their blessing to North Carolina's stable, agrarian, republican way of life.

First State University Founded

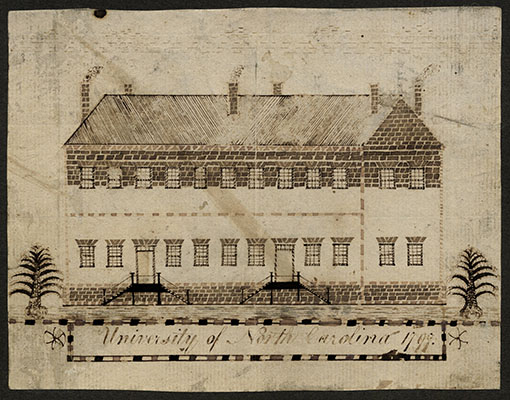

The most conspicuous collaborative project of the planters and the evangelicals was the University of North Carolina. Led by General William Richardson Davie, prominent secular politicians believed that a university to train each rising generation of the elite in the principles of science, reason, and virtue would be an incomparable asset for the future of North Carolina. Prominent Presbyterian clergy, inspired by the Reverend Samuel E. McCorkle, hoped that a religiously oriented school would train future ministers in Greek, Latin, and moral philosophy, while preparing other godly youths for honorable service in diverse fields. Both groups urged the legislature to act, and the University of North Carolina was the result.

Chartered in 1789, the college opened in 1795 as the first state university in America. McCorkle devised the first curriculum; it stressed moral education and the classical languages of Latin and New Testament Greek. A little later, the trustees substituted a different course of study proposed by Davie. The new curriculum was more practical, stressing modern languages and mathematics. A student could, if his parents chose, avoid the "dead" languages altogether and earn an English diploma that was based on the study of science and mathematics and their practical applications. In Davie's view, there was more virtue to be found in skills useful for the new country than in the ambiguous speculations of philosophers, theologians, and dead poets. Under the Reverend Joseph Caldwell, the university's first president, a compromise was struck that provided for more secular versions of the traditional classical subjects.