See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Roanoke and Jamestown

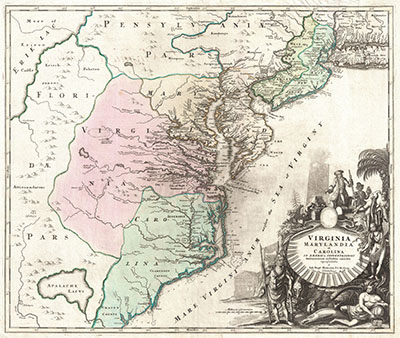

After the failure of English settlement efforts at Roanoke, Native American people in North Carolina remained undisturbed for decades. When European intrusions finally did recur, they came not from the sea, but overland from the Virginia colony to the north. Indeed, the territory we now know as North Carolina was for years included in the tremendous Virginia Company land grant of 1606. In that year, to raise sufficient funds to finance another attempt at English colonization in the New World, King James I chartered the Virginia Company of London, a joint-stock company of merchants who hoped to make fortunes in mining and trade with Native American people. Thus, the first permanent European settlements, in the far northeastern corner of North Carolina, were more an extension of the Virginia Company's colony at Jamestown, Virginia, than they were concerted efforts toward planting a new colony.

As early as 1608 Captain John Smith sent two explorers from Jamestown into what would become North Carolina. Instructed to search for survivors of the Roanoke settlement, the two woodsmen probed about the Chowan River region and then returned.

Colonists Move South

Still other poor colonists chose to migrate southward into the Albemarle region. By 1655, in the area east of the Chowan River and south of the Great Dismal Swamp, North Carolina had its first permanent English settlers.

In 1663 Charles II, recently "restored" to the English throne, formally granted by charter the Province of Carolina—from present-day Florida north to the Albemarle Sound region, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Pacific—to eight favored courtiers. These men were known as the Lords Proprietors, and the region given to them was named Carolina (or Carolana) in honor of Charles I.

By 1663 the immigrant population of the tobacco-growing Albemarle region had passed 500. Scores of Virginians moved southward annually. Some years later, William Byrd, wealthy Virginia planter and surveyor of the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia, disparagingly described the migrant settlers to the Albemarle region. They were, he said, Quakers and Anabaptists, particularly "a swarm of Scots Quakers," who "inveigled many over [to the region] by this tempting Account of the Country: that it was a place free from those 3 great Scourges of Mankind, Priests, Lawyers, and Physicians."

Among the immigrants was Joseph Scott, who in 1684 acquired property in a Quaker community near the Perquimans River. Scott's farm passed through several generations until Abraham Sanders, a Quaker, purchased the farm then known as Vineyard in 1727. Sanders had migrated from Virginia around 1715 and soon married Judith Pricklove, the granddaughter of Quaker leader Samuel Pricklove, one the Albemarle's earliest inhabitants. On this tract acquired from Scott, Sanders around 1730 built the dwelling now known as the Newbold-White House, one of the oldest standing buildings in North Carolina.

Struggles in the Albemarle

In the early years of the Albemarle settlement, however, the raising of crops and livestock, and indeed everyday life itself, could prove difficult and precarious. Violent storms, hurricanes, and droughts destroyed crops and livestock alike, as documented by Peter Carteret, who served as governor from 1670 to 1672. He reported that in 1667 a hurricane "destroyed both corne & tob: blew downe the roof of the great hogg howse." In 1668 first drought and then torrential rains ruined crops. Another hurricane struck in 1669 and, according to Carteret, "destroyed what tob was out... & spoiled most of the corne this yeare." The following year, a twenty-four-hour hurricane blew down trees, houses, and the "hogg howse." Conditions were so bad that Carteret proclaimed there was bound "to bee a famine amongst us." In 1709, William Gordon, an Anglican missionary, described the poor living conditions of most Carolinians, who were "destitute of good water, most of that being brackish and muddy; they feed generally upon salt pork, and sometimes upon beef, and their bread of Indian corn which they are forced for want of mills to beat; and in this they are so careless and uncleanly that there is but little difference between the corn in the horse's manger and the bread on their tables." He further noticed that perhaps the colony was "capable of better things, were it not overrun with sloth and poverty."

Thus many of the colonists who fled south from Virginia in search of a better and more prosperous life discovered only a harsh and hostile existence in Carolina. And among the migrants, it would be the ever-increasing numbers of enslaved Africans and their descendants who would suffer the greatest hardships. In 1712, the number of enslaved Black people in the whole colony totaled only 800. But in their Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina in 1669, the Lords Proprietors made slavery an established and protected institution by emphatically declaring in Article 110: "Every Freeman of Carolina, shall have absolute Power and Authority over his Negro Slaves, of what Opinion or Religion sover." Some Black people, though, fled to the Albemarle to escape from bondage in Virginia. "It is certain," wrote William Byrd, that "many Slaves Shelter themselves in this Obscure part of the World, nor will any of their righteous Neighbors discover them." Despite the difficult circumstances that early Carolina immigrants—white and Black—found awaiting them, the colony grew as new arrivals continued to spread throughout its borders and towns began to appear on the landscape.