19 Sept. 1778–23 Jan. 1844

William Gaston, lawyer, legislator, congressman, and jurist, was born in New Bern. His father, Alexander Gaston of Huguenot ancestry, was a native of Ireland, trained in medicine, and served as a surgeon in the British navy before settling in Craven County prior to May 1764. His Roman Catholic mother, Margaret Sharpe, went to New Bern from England nine years later. In May 1775, she married Dr. Gaston, who became an ardent patriot with the advent of the American Revolution. He was killed by a party of Tories in August 1781, leaving a widow and two children, William and Jane. Thereafter, the pious and intelligent Mrs. Gaston proceeded to mold her son's character and to instill in him a lasting devotion to the Roman Catholic church. This upbringing in time made Gaston worthy to be called "the greatest lay Catholic in America."

Gaston's formal education began in 1791. After a five-month visit in Philadelphia, he arrived in the autumn of that year in Georgetown on the Potomac River to enroll as the first student at Georgetown College, a recently founded Roman Catholic institution of higher learning. III-health, however, compelled him to leave in the spring of 1793. Back in his native town, Gaston regained his strength and spent the next year as a student at New Bern Academy, where he gave the valedictory in July 1794. After another sojourn in Philadelphia, he was admitted in November to the junior class of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, from which he was graduated at age eighteen at the head of his class. Gaston then returned to New Bern to study law under François-Xavier Martin, an eminent attorney. He developed such legal competence that he was admitted to the bar in September 1798. He immediately took over part of the law practice of his brother-in-law, John Louis Taylor, who had been selected a superior court judge. Although Gaston excelled in land cases, he also emerged as a superlative criminal lawyer. A number of students prepared for the bar under his direction.

Politics soon attracted Gaston's attention, and he proved to be an energetic Federalist leader. In 1800 he was elected to the state senate, where he served on several committees and was chairman of three others. He was sent to the House of Commons in 1807, 1808, and 1809. In 1808 he was chosen both speaker of the house and a presidential elector. He ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810, but again won a seat in the state senate in 1812. The next year he went to Washington as a member of the House in the Thirteenth Congress. He gained experience on several relatively minor committees before working on the important Ways and Means Committee; he was reelected to the Fourteenth Congress. As a congressman Gaston gained a national reputation for the eloquence of his speeches, especially those supporting the Bank of the United States and opposing the Loan Bill, by which President James Madison was to be entrusted with $25 million for the conquest of Canada. He denounced generally the War of 1812 as "forbidden by our interests, and abhorrent from our honour." His speech in reply to Henry Clay's "defense of the previous question" was a particularly noteworthy piece of parliamentary oratory. In January 1815 he presented a petition asking for authority for Georgetown College to award academic degrees. A congressional charter for the school resulted. In 1817, he voluntarily retired from Congress and resumed the practice of law. Daniel Webster, one of many national figures known by Gaston, described him as the greatest man of the War Congress.

Craven County sent Gaston to the state senate in 1818 and 1819. At both sessions he served as chairman of the Judiciary Committee; he was also chairman of the joint legislative committee that in 1818 framed the act creating the North Carolina Supreme Court. Although Gaston never reentered national politics after leaving Congress, President John Quincy Adams considered naming him secretary of war in 1826 because of his faithful support of the administration. In a circular prepared by Gaston for the Committee of Correspondence and Vigilance of New Bern, he announced that the president's wisdom and honesty entitled him to a second term. In his keynote address to the anti-Jackson convention in Raleigh in December 1827, he once more urged that Adams be reelected. Gaston was returned to the House of Commons in 1827 to fill the vacancy for New Bern occasioned by John Stanly's resignation. The next year he was elected to the lower house for a full term and was returned to that body in 1829 and 1831. Besides serving on the judiciary committee during these years, Gaston was chairman of the finance committee, a position that coincided with his interest in banking. In 1828, he was appointed president of the Bank of New Bern and while in the house was able to cooperate with conservative financial groups in an effort to maintain sound banking policies for North Carolina.

He also took a lively interest in internal improvements for the state. In 1827, he was elected the first president of the Agricultural Society of Craven County. The same year he was a delegate to a convention in Washington, N.C., for the purpose of deciding on ways to improve navigation at Ocracoke Inlet; he then tried to help put the measures agreed upon into effect. In July 1833 he attended an internal improvements convention in Raleigh, serving as chairman of the committee to prepare an address to the state and to lay the convention's proceedings before the state legislature. The address, which was his own handiwork, stressed the need for colleges, railroads, hospitals, and asylums for the handicapped. As a member of the House of Commons, Gaston had the satisfaction of introducing the bill to charter the North Carolina Central Railroad.

Gaston's career as a public servant entered a new phase in November 1833, when the General Assembly elected him to the North Carolina Supreme Court. Although Article 32 of the state constitution denied the right to hold state office to anyone who did not believe in "the Truth of the Protestant Religion," Gaston and the politicos concluded that a Roman Catholic was not disbarred by the provision. More than thirty years earlier, former governor Samuel Johnston had given him a written opinion expressing approbation when Gaston first became a member of the state legislature. His most famous decision on the bench came in 1834 with the case of State v. Negro Will. Gaston ruled that an enslaved person had the right to defend himself against an unlawful attempt of an enslaver, or an agent of an enslaver, to kill him. In the significant case of State v. William Manuel in 1838, he held that a manumitted enslaved person was a citizen of the state and thus entitled to the guarantees of the constitution. This opinion was cited as "sound law" in 1857 by Benjamin R. Curtis of the United States Supreme Court in his dissent in the Dred Scott case. The better for the justices to render decisions, Gaston purchased a library for the state supreme court while on a trip to New York City in 1835. When Chief Justice John Marshall died that year, there was speculation that Gaston would succeed him on the United States Supreme Court, a possibility championed by various state newspapers.

Elected by Craven County as its representative to the Constitutional Convention of 1835, Gaston spoke out in favor of continued suffrage for free Blacks, federal representation as the basis for representation in the House of Commons, and biennial meetings of the state legislature. However, it was to the fight against Article 32 of the state constitution that he gave most of his considerable oratorical skills, delivering a two-day address against religious tests for public office. In the end, the attempt to expunge all religious qualifications from the constitution failed, but the word "Christian" was substituted for "Protestant." Gaston served on the committee appointed at the convention to draft the proposed amendments to be submitted to the voters of North Carolina.

A deeply religious man, Gaston was also an active Roman Catholic. When Bishop John England visited New Bern from Charleston, S.C., in May 1821, he celebrated in the parlor of the Gaston house his first recorded mass in North Carolina. The bishop designated Gaston one of five Catholics to conduct services every Sunday in the improvised chapel; at the same time a treasury, to which Gaston contributed $700, was established to receive funds for a church building. Appointed a church warden in February 1824, on another visit by England, Gaston suggested a few amendments to the constitution for the Catholic church in North Carolina which the bishop published in New Bern. Plans for a wooden church were finally presented at a meeting in Gaston's law office in October 1839, and he pledged an additional $500 towards the amount needed to construct the edifice. A contract was drawn up between Gaston and the builder the next year. Work on the church was completed in 1841, thus making St. Paul's Church the oldest Roman Catholic church in North Carolina.

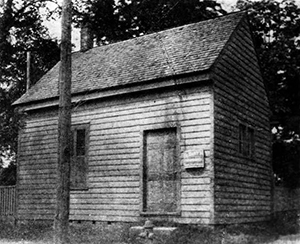

Gaston, who owned slaves and a plantation in Craven County, purchased a townhouse in New Bern in April 1818. Built about 1767 by James Coor, this fine Georgian structure is one of the few relatively untouched pre-Revolutionary frame buildings in North Carolina. It is particularly distinguished by its Chinese Chippendale balustrades on the double porches. The Gaston house, placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, has been restored by the Judge Gaston House Restoration Association. Gaston's restored law office stands one block from his house in New Bern.

During the sessions of the supreme court in Raleigh, Gaston stayed at the home of Mrs. James F. Taylor. At his office nearby, in 1835 he wrote the words for "The Old North State," the music for which he apparently adopted from a melody sung by a group of Swiss bellringers who had visited the capital. A bronze tablet at the site of the office commemorates the writing of what has been since 1927 the official state song of North Carolina. It was played in public for the first time at the Whig state convention in Raleigh in October 1840. Gaston, himself now a Whig, took no direct part in the presidential campaign of that year, but to the Whigs in control of the state legislature he became the leading choice for the U.S. Senate. He declined the offer as he likewise turned down the next year the post of attorney general in the cabinet of President William Henry Harrison. His name had often been presented by newspaper editors to the country as a vice-presidential prospect.

The honors bestowed upon Gaston in his lifetime reflect the esteem in which he was held throughout the United States. In 1817 the American Philosophical Society elected him a member, and two years later the American Antiquarian Society made him counselor for his state. In 1819 the University of Pennsylvania conferred on him the honorary degree of doctor of laws, a degree similarly awarded him later by Harvard College and Columbia College. He was a member of the American Academy of Languages and Belles Lettres and an officer of the Cliosophic Society and of the Literary Society of the College of New Jersey. In 1835, the Philodemics Society of Georgetown College made him an honorary member, as did the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Yale College. Over the next few years he was elected to honorary membership by the literary societies of the University of Alabama, Rutgers College, the University of Georgia, St. Mary's College of Baltimore, Caldwell Institute, and Davidson College. He also belonged to the Erodelphian Society of Miami University, the Franklin Society of Randolph-Macon College, the Philo Society of Jefferson College in Cannonsburg, Pa., and the Euzelian Society of Wake Forest College. Gaston served as a director of the state institution for the instruction of the deaf and dumb, a trustee of the Griffin Free School in New Bern, and a trustee of The University of North Carolina from 1802 until his death.

With his recognized speaking ability, Gaston was invariably called upon to deliver commencement addresses by colleges and universities far and wide. One of his most outstanding orations he gave in June 1832 at The University of North Carolina, where he entreated his audience to uphold the Constitution and to preserve the Union. He condemned the institution of slavery and insisted upon its abolition, although at the time of his death he owned over 200 enslaved people. He stated his antinullification position so emphatically that his address went through five printings, one of which carried a preface written by his friend Chief Justice John Marshall. In 1830, 1834, and 1835, the College of New Jersey asked Gaston to give the commencement address, as did Wake Forest College and The University of North Carolina in 1834. Many times he was requested to send copies of his different speeches to editors collecting oratory masterpieces for publication.

Gaston made out his will in December 1843, citing among his legatees his surviving daughters, grandchildren, and St. Paul's Church. The next month he suddenly became ill while hearing a case in Raleigh and died in his office several hours later. His last words were said to have been: "We must believe there is a God—All wise and All mighty." He was buried temporarily in Raleigh; his remains were later moved for interment in Cedar Grove Cemetery, New Bern. There Gaston was laid to rest near his parents in a grave marked by a fine marble tombstone.

Gaston was married three times: on 4 Sept. 1803, to Susan Hay; on 6 Oct. 1805, to Hannah McClure; and on 3 Sept. 1816, to Eliza Ann Worthington. By his second wife, he had one son and two daughters and by his third, two daughters.

Several portraits of Gaston exist. Early in his public career he was asked for a portrait to be hung in the National Gallery in Washington. Portraits are also owned by his descendants and by the Philanthropic Society of The University of North Carolina, which possesses a fine oil on canvas. A portrait of Gaston was given to the state supreme court in 1893; another has hung in his law office in New Bern since 1954. A marble bust of Gaston is located in the Philanthropic Society Hall in Chapel Hill. One of the most interesting likenesses of Gaston is a small watercolor on ivory executed by James Peale in 1796. Gaston stood six feet tall, with blue eyes and dark hair. As he grew old, he became somewhat stout, his complexion got florid, and his hair turned gray. His face, according to a friend, continued to express "the benignity of soul which animated his life."

A treasure trove of material is located in the William Gaston Papers in the Southern Historical Collection at The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. This valuable collection consists of much of Gaston's personal, business, and political correspondence over the years from 1791 to 1844. The William Gaston Papers in the North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, contain a much smaller number of items. Gaston County and Gastonia are both named in honor of this remarkable man.