See also: State v. John Mann.

State v. Negro Will, a 1834 North Carolina Supreme Court decision standing for the general proposition that if an enslaved person in self-defense, under circumstances strongly calculated to excite passions of terror and resentment, kills an enslaver, the homicide is not murder but manslaughter. Justice William Gaston wrote the opinion for a unanimous court.

On January 22, 1834, a black man named Will - referred to as Negro Will, enslaved by James S. Battle of Edgecombe County, had a dispute with Battle's enslaved foreman, Allen, regarding the possession of a hoe. As a result of the dispute, Will broke the hoe and then went to a nearby cotton mill to work. On learning of Will's conduct, Battle's white overseer, Baxter, seized his loaded gun, mounted his horse, and ordered Allen to follow with a cowhide whip. Accosted by Baxter, Will attempted to run away, when Baxter shot him in the back. The wounded fugitive continued to flee but was intercepted by Baxter. In the ensuing struggle, Will delivered knife wounds to Baxter's thigh, chest, and arm of which Gaston deemed the loss of blood from the arm wound to be fatal. The Edgecombe County Superior Court found Will guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced him to die.

After investigating the situation, Battle was convinced that Will had acted in self-defense under extreme provocation. Determined to see that Will received justice, the enslaver engaged two leading members of the bar, Bartholomew F. Moore and George Washington Mordecai, to represent him; to Moore, Battle paid the extraordinary fee of $1,000. Moore and Mordecai took Will's appeal to the state supreme court, where they were opposed by Attorney General J. R. Daniel.

In his brief and oral argument before the supreme court, Moore demanded that the law display a humane attitude toward Will. He maintained that Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin's 1829 decision in State v. John Mann, in which Ruffin had written that "the power of the master must be absolute in order to render the submission of the slave perfect," was abhorrent and at variance with prior case law. Although it disagreed with Moore on this point, the court unanimously reversed Will's conviction.

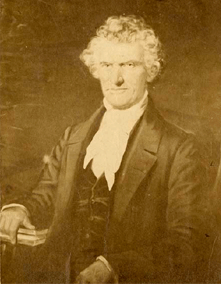

Writing for himself, Ruffin, and Justice Joseph J. Daniel, Justice Gaston reasoned that, had the homicide been committed by free man upon free man, it could have been no more than manslaughter; if between master and apprentice, the deed could have been attributed to "a brief fury" that did not leave the mind capable of the sort of calm, rational thought required for murder. In forceful language, he continued: "If the passions of the slave be excited into unlawful violence by the inhumanity of a master . . . is it a conclusion of law that such passion must spring from diabolical malice?"

Gaston's opinion was lauded by moderate antislavery forces throughout the country; passages were quoted in prominent newspapers and law journals. In silent tribute, abolitionist commentators ignored the decision, presumably because it had scant potential for propaganda. Beginning in the 1890s, historians praised Will's "humanity;" the case supposedly did much to abate the harshness of prior law, such as Ruffin's opinion in Mann.