9 Apr. 1774–2 Aug. 1833

John Stanly, Federalist congressman and legislator, was born in New Bern. His father, John Wright Stanly, was the most famous shipowner in North Carolina during the American Revolution; his mother was Ann Cogdell, the daughter of Richard Cogdell of New Bern. His father and mother died in 1789, and this double calamity interrupted his studies with private tutors, studies that were never regularly resumed. The six orphaned children of John and Ann Stanly were left in greatly reduced circumstances, and John became a clerk for his father's partner, Thomas Turner.

In 1795, at age twenty-one, he began a brief career as a merchant in New Bern. That year he married Elizabeth Franks, who inherited from her father large estates in Jones County. Association with prominent New Bern lawyers, particularly Benjamin Woods and Thomas Badger, and an appointment as a district court clerk and master of equity, led him to study law without regular instruction; in 1799, "after a mysterious disappearance of a few days from the town," he returned with a license to practice. Endowed with both mental and personal gifts, Stanly soon attained prominence in his profession and became perhaps the most accomplished orator in the state. In the courtroom his quick perception, retentive memory, keen wit, and bitter invective made him a formidable antagonist. He was equally at home in private conversation.

Stanly devoted the best of his energies and much of his life to politics. William Gaston, one of his closest friends, later testified that "public interests seemed to afford to his ardent mind that peculiar excitement in which he delighted, and to give it that full employment without which it was ill at ease." Entering public life in 1798 as an "uncompromising Federalist," Stanly succeeded Edward Graham as New Bern's representative in the North Carolina House of Commons and was reelected the following year. In 1800, despite the general enthusiasm for Thomas Jefferson, the Federalists elected four congressmen, including Stanly—then but twenty-six—who defeated the ailing incumbent Richard Dobbs Spaight in the New Bern district. On 5 Sept. 1802 Stanly mortally wounded Spaight in a duel growing out of their continuing political quarrel and forced by Spaight. The widow's kinsmen threatened criminal proceedings against Stanly, but on his petition, Governor Benjamin Williams pardoned him.

A candidate in 1803 for reelection to the House of Representatives, Stanly was defeated by William Blackledge as the Republicans made a clean sweep of the congressional races. In 1808, however, the Federalists capitalized on popular discontent against Jefferson's embargo and captured three House seats, with Stanly winning over Blackledge. In the Eleventh Congress he was an outspoken opponent of the Madison administration and the so-called War men who were advocating the strongest retaliatory measures against Great Britain for violations of American neutral rights. North Carolina Federalists took great pride in Stanly, pointing out that northern papers praised him and printed his speeches while generally ignoring his Republican colleagues. Despite this praise he was not a candidate for reelection in 1810, and Blackledge was again returned to Congress, defeating William Gaston. Stanly remained an unreconstructed Federalist of the Washington-Marshall stamp to the end of his life. As he declared proudly in the House of Commons in 1824, when the Federalist party in the South was just a memory: "For myself, I thank God, I can say I am still a Federalist. I never have, and I never will put on the turban and turn turk, for any share of the plunder."

North Carolina Federalists were critical of "Mr. Madison's War," as they termed the War of 1812, but unlike their dissatisfied party brethren in New England, they considered disunion a greater curse than the evils of Republican rule. As Stanly wrote Gaston when word of the Hartford Convention reached New Bern, "The severance of the Union is an evil of such magnitude, that I cannot apprehend any man of standing & influence will meet the responsibility of recommending such a resort—weighty as are the evils & curses of Madison's administration, those of disunion would be so much more awful, that I will not yet believe that the patriots of New England contemplate any such resort." Yet despite their loyalty to the Union, the North Carolina Federalists shared some of the odium that fell on the New England Federalists in their twilight years as a consequence of the Hartford Convention. No talented Federalist in the state could aspire to either the governorship or the U.S. Senate, and few were elected to the House of Representatives. Unquestioned devotion to Jeffersonian principles was the sine qua non of political advancement.

Although Stanly's Federalism thus barred him from the highest political offices, he remained a power in state affairs. New Bern sent him to the House of Commons in 1798–99, 1812–15, 1817–19, and 1823–27, and in 1821 he was one of the Craven County members of the house. Possessing "an eye like Mars, to threaten and command," he "held a rod pickled in . . . Sarcasm" over the western members. After Republican proscription of Federalists had eased, he was elected speaker in 1825 and 1826 and won high praise for his performance. On 4 Dec. 1825 David F. Caldwell, a member from Salisbury, wrote Willie P. Mangum: "Mr. Stanly whom I fear you are not partial to presides over us with impartiality, dignity & ability. He certainly gives a dignity to the deliberations of the commons, & preserves a degree of decorum which I have never witnessed."

On 16 Jan. 1827 Stanly suffered a paralytic stroke while speaking in the committee of the whole. He remained in critical condition for weeks, and friends feared for his sanity. His health improved somewhat in the summer of 1827, and he gave limited support to Andrew Jackson in the election of 1828. In 1824 he had endorsed the People's ticket while stating a preference for John C. Calhoun or John Quincy Adams. Stephen F. Miller, during a visit to New Bern from Georgia in 1829, found his "noble features" distorted by his affliction. "He tried to converse in his former commanding way, but failed." His friends, as a complimentary gesture, placed his name before the General Assembly in 1828 as a candidate for governor; Stanly received twenty-one votes on the first ballot, but his name was withdrawn on the second ballot.

During his long illness debts accumulated, reportedly because his sons were improvident. Creditors pressed claims, and only Gaston's intervention saved the Stanly mansion from sale. Mrs. Stanly had to advertise for boarders. The end finally came on 2 Aug. 1833 (not 1834 as usually stated), when he was fifty-nine. He was buried in the Episcopal cemetery in New Bern. "He was indeed a great man," Gaston wrote later, "distinguished pre-eminently for acuteness of intellect, rapidity of conception, a bold and splendid eloquence. How unfortunate it has been for his family that he lived so much for others and so little for himself." Stanly County, formed in 1841 from Montgomery, was named in his honor.

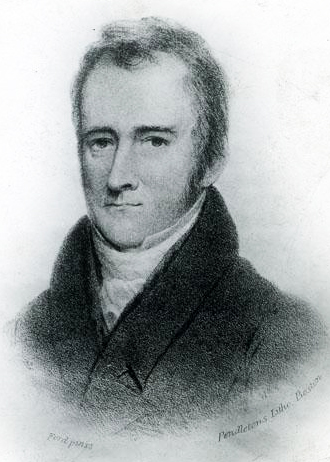

John and Elizabeth Stanly had fourteen children, five of whom died young. There were eight living sons: John (idiotic from birth), Alfred, Frank, Edward, Alexander Hamilton, Fabius Maximus, Marcus Cicero, and James Green. Elizabeth Mary, the only daughter to reach adulthood, married Captain Walker Keith Armistead, a West Point graduate, against her father's wishes. A son, Lewis Addison Armistead, born to the couple in New Bern on 18 Feb. 1817, fell at Gettysburg on 3 July 1863 while leading the remnants of Pickett's division into the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge. A portrait of Stanly—an oil on canvas (28 by 23) by an unidentified artist—was owned by John Gilliam Wood of Hayes, Edenton.