See also: Salem Tavern; Travelers' Rooms.

Inns and taverns played an important role in the economic and geographic development of colonial North Carolina. These establishments-also known as "ordinaries" in eighteenth-century America because they often catered to the full spectrum of social classes-were frequently one of the first businesses to appear in newly designated county seats, offering food and lodging to travelers and visitors to court. Consequently, inns and taverns provided a variety of goods and services, from meals and liquor to overnight accommodations. While colonial law required innkeepers to provide suitable lodgings at a reasonable price, exactly what constituted "suitable" was always in question. Travelers staying the night might find themselves sharing a bed with two or three others, if they were lucky enough to get a bed at all. Not surprisingly, many female travelers avoided sleeping or eating at public inns in favor of private homes.

Various wines, beers, hard ciders, and exotic punches were standard offerings on the drink menus of early North Carolina taverns and public houses. Many well-known eighteenth-century establishments regularly served liquor-based toddies to weary patrons in need of relaxation after a long day of difficult travel. The drinks' potency and warmth, and the addition of nutmeg or other spices, made toddies particularly welcome in colder months. They were also widely considered elixirs with great medicinal value, effective against symptoms of viruses, nervous conditions, and other ailments.

Tavern keepers adhered to strictly enforced laws requiring them to post their rates for meals, beverages (especially liquor and spirits), and some services. With a built-in local customer base, tavern keepers frequently branched out into auxiliary economic endeavors to provide other services for their customers and make a larger profit. Taverns that doubled as ferry (and later, stage) stops and inns that housed general merchandise stores were popular combinations.

Perhaps North Carolina's most famous colonial tavern is Salem Tavern, located in the heart of Old Salem. Its structure, which is currently a museum located next to a full-service restaurant, dates to 1784, when it was reconstructed after an earlier wooden tavern burned to the ground. Person's Ordinary, in the present-day town of Littleton, was originally licensed to Thomas Person in 1764 and again to William Person Little in 1820. The small frame building served for several generations as a way-station to travelers on the "high" or "stage-coach" road between Hillsborough and the town of Halifax. Stories of duels surround the early history of the ordinary. One, related by Rebecca Leach Dozier in her history of Littleton and credited to an enslaved person identified as "Mammy Lissa," describes a Revolution-era duel between a Whig named Drugger and a Tory named Drumghould, wherein Drugger eventually kills his opponent over a political insult.

Pop Castle was a legendary inn and recreation center in colonial Granville County at a site now in Vance County, one mile west of Kittrell. It was reputedly first occupied by an unidentified nobleman, a political refugee from Europe, and later owned by one Captain (Nathaniel?) Pope, a pirate who was said to have buried gold nearby. Known for a time as Popecastle Inn, it was soon altered to Pop Castle by local usage after an adjoining cockfighting pit and tavern began to attract people. A racetrack was laid out during the Revolution. The main building of the inn was finally taken down after the Civil War. The site was marked by a large lone oak tree for many years, but myths of Pop Castle survived into the twentieth century.

Hunter's Tavern in Wake County was established by Isaac Hunter in 1769 on land probably deeded to him by his father, Theophilus Hunter. When the North Carolina legislature convened at Hillsborough during the summer of 1788 to consider ratification of the U.S. Constitution, it also decided the site of the permanent capital of the state. Several places were proposed, including "Mr. Isaac Hunter's in Wake County," which was nominated by James Iredell. On 2 Aug. 1788 it was chosen, and thus the capital of North Carolina was to be erected within ten miles of Hunter's Tavern. Commissioners selected by the General Assembly to select a specific site met at Hunter's Tavern on 20 Mar. 1792. Hunter apparently hoped to sell land for the capital, but the commissioners adjourned to the residence of Joel Lane, from whom they eventually purchased land. Hunter sold the tavern property in 1801 to William Camp, husband of his daughter Elizabeth. The property passed through the hands of several owners, including the late J. Crawford Biggs. The North Raleigh Hilton is currently located on the site of Isaac Hunter's tavern.

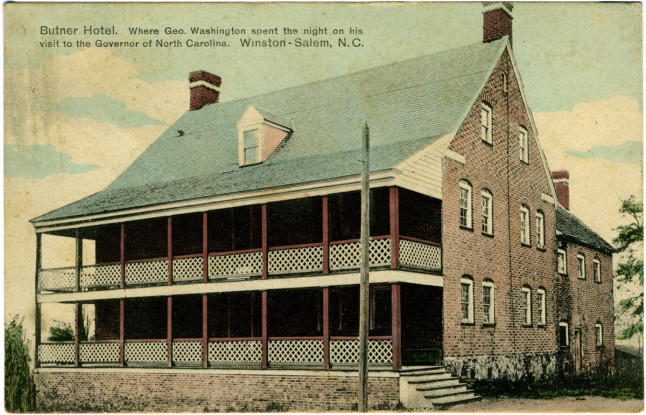

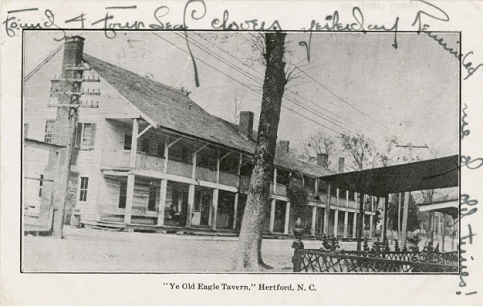

Eagle Tavern was a hostelry that welcomed visitors to Hertford, the seat of Perquimans County, from colonial times to the beginning of the twentieth century. From a modest beginning in 1762 in the home of Charles Jordan, the tavern ultimately became a sprawling multistory frame structure of 25 rooms that covered six lots at the corner of Church and Grubb Streets. George Washington purportedly stayed at the Eagle while he was engaged in the survey of the nearby Great Dismal Swamp. Among other famous eighteenth-century guests was William Hooper, one of North Carolina's three signers of the Declaration of Independence. The old rambling building was razed in 1915.

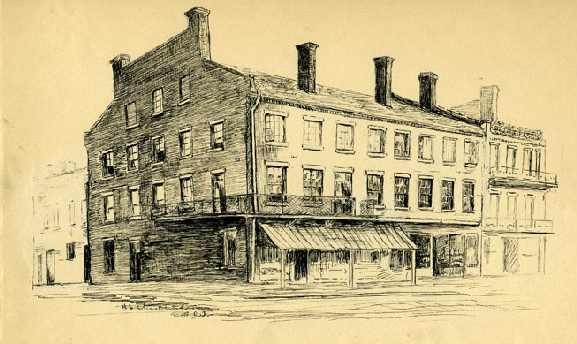

Casso's Inn was the largest and most popular hostelry in the early years of Raleigh. The inn (sometimes called a tavern) was best known for a traditional association with Andrew Johnson, seventeenth president of the United States. Built between 1790 and 1795 by Peter Casso, who had come to Raleigh from Beaufort County, the inn stood on the northeast corner of Fayetteville Street (Lot 162 in the plan of the city) diagonally across from the statehouse. Its only competitor was the Indian Queen, which it quickly surpassed in patronage and size. Despite the popularity and apparent success of his inn, Peter Casso proved to be an inefficient businessman. By 1799 he had established a pattern of indebtedness from which he would never recover.

Local tradition maintains that Andrew Johnson's mother, Mary "Polly" McDonough, worked at Casso's Inn as a weaver before she married Jacob Johnson, and that Andrew was born in one of the kitchens then serving as the Johnsons' home. Extensive research neither upholds the truth of the story nor proves it false beyond a doubt. In the absence of conclusive evidence to the contrary, the tradition will continue to claim a place in the history of Casso's Inn.