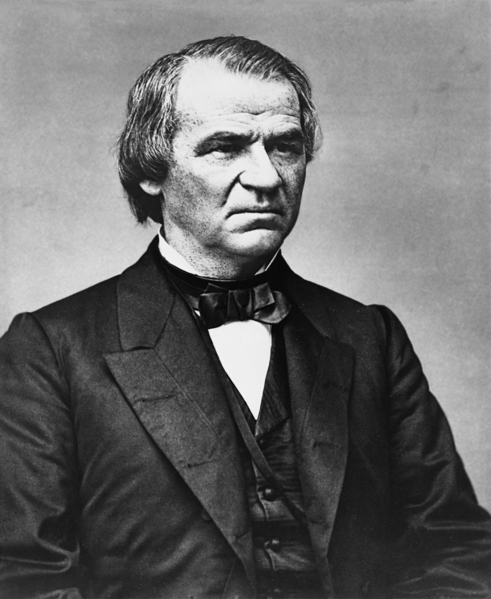

December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875

See also: Johnson, Andrew, from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography.

Let peace and prosperity be restored to the land. May God bless this people: may God save the Constitution.

- Andrew Johnson in the U.S. Senate

March 22, 1875

[Please note: The complexity of the Reconstruction period precludes even the barest sketch of the issues surrounding Andrew Johnson's Presidency. Readers with an interest in this period are advised to consult some of the sources listed in the bibliography at the end of this profile.]

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1808, and like the previous North Carolina-born presidents, Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk, he was elected to office from Tennessee. Although a native of the South, Johnson was a firm supporter of the Union. During the desperate days of the Civil War, he served as the military governor of Tennessee and finally as vice-president under the second term of Abraham Lincoln. After Lincoln's assassination, the heavy task of restoring a nation after the ravages of a civil war fell to the tailor from North Carolina.

Andrew Johnson began his life in a small wooden house, which is still preserved in Raleigh at the Mordecai Historic Park

. His parents, Jacob and Mary Johnson, maintained the home by working for Casso's Inn, a popular inn and stable. The Johnson home stood on the property of the inn. Both of Andrew's parents worked there--Mary as a weaver, Jacob as the hostler, while Jacob also acted as janitor for the State Capitol. Andrew was the younger of two sons born into the Johnson family. Jacob Johnson rescued two or three friends (recollections were unclear) from drowning in 1812, but the effort cost him his health, and he died within a year, leaving Mary to raise Andrew and his brother William. In an effort to provide a trade for her sons, Mary Johnson apprenticed her sons to a tailor in Raleigh when Andrew was fourteen.

Andrew Johnson never attended school. He began his informal education while serving as an apprentice. Frequent customers would read to Johnson from books of oratory while he worked, and occasionally gave him books. Johnson taught himself to read. Two years after beginning his apprenticeship, Johnson and his friends threw rocks at a tradesman's house out of mischief. When the occupant of the house threatened to call the police, Johnson left town and abandoned his apprentice work at the tailor shop of John J. Selby. Johnson fled to Carthage, North Carolina sixty miles from Raleigh. He found a market for his tailoring skills in Carthage but moved to Laurens, South Carolina to distance himself further from the trouble in Raleigh. After a year in Laurens, Johnson returned to Raleigh and sought to complete his apprenticeship under John Selby. Selby, however, no longer owned the tailor shop and had no need of an apprentice. With no available employment in Raleigh, Johnson led his mother, brother, and stepfather to Tennessee in 1826.

Andrew settled the family in Greeneville, Tennessee, and established a tailor's shop by nailing a sign over the door stating simply, "A. Johnson, Tailor." Soon Johnson met Eliza McCardle, and the two were eventually wed on May 17, 1827. Mrs. Johnson was better educated than her husband and used her education to improve his reading and writing skills. She also taught the future president arithmetic. She continued the established practice of reading to Johnson while he worked.

Business improved for Johnson, and his shop soon became a gathering place for political discussion. Johnson honed his debating skills further by joining a debate club at a small college four miles from his home, walking to the debates once a week. With encouragement from his wife and speaking experience gathered both in his shop and at his debate club, Johnson entered politics.

Andrew Johnson's political career advanced rapidly. He was elected as an alderman of Greeneville, Tennessee, in 1828, and two years later he became mayor of the town. In 1835 Johnson won election to the Tennessee House of Representatives. He was defeated for re-election in 1837 but won a subsequent campaign in 1839. After completing this second term, Johnson ran for a seat in the Tennessee Senate and won. Johnson continually supported the rights of free laborers. While in the state senate he sought to repeal a law providing greater representation to slaveholders, but his motion was defeated. Johnson was also unsuccessful in his effort to create a new state from the Appalachian regions of North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Tennessee to be named Frankland.

At the conclusion of his senatorial term in 1843, Johnson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and won four following elections to retain his seat until 1853. While in the U.S. House, Johnson supported President Polk and his handling of the Texas and Oregon settlements and the Mexican War. Although hailing from a Southern state, Johnson was often a staunch supporter of the Constitution over State's Rights, a position which conflicted with many Southern legislators. Turning his sights back to state politics, Johnson won the 1853 Tennessee gubernatorial election and re-election in 1855. Johnson's star continued to rise, and his term as governor of Tennessee provided such benefits to the state as a public school system and a state library. On the eve of the Civil War in 1857, Johnson was elected to the U.S. Senate.

The final act leading to the Civil War occurred during Johnson's service in the Senate. Johnson was a Southerner and supporte

d the Fugitive Slave Law and defended slavery. He also supported Abraham Lincoln's chief opponent in the 1860 presidential election, Stephen Douglas. However, he also spoke sternly against both secessionists and abolitionists as dangerous to the existence of the Union and the Constitution. By the 1860 presidential election, several Southern states had already formed a confederacy. Abraham Lincoln won the November election winning forty percent of the votes cast, and in the following April South Carolina batteries bombarded Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor beginning the Civil War. Andrew Johnson warned that the dissolution of the Union would produce many minor countries ruled by various forms of government. In spite of Johnson's strong support of the Constitution and the Union, Tennessee seceded from the United States. Johnson rejected the Confederacy and was the only Southern senator to remain in the U.S. Senate after secession. Johnson's support of the Union won acclaim in the North and infamy in the South. Eastern Tennessee possessed strong pro-Union factions, but pro-Confederacy forces from the central and western parts of the state secured the state for the South. When war erupted Tennessee was an early battlefield. Union victories in the state placed large parts of the state in federal control, and occupied areas were administered by appointed military governors.

In 1862 President Lincoln appointed Andrew Johnson as military governor of Tennessee. Johnson ruled with a firm hand silencing sources of anti-Union sentiment. Johnson held the military governorship of Tennessee until 1864. Preparing for the presidential election, foreseeing an imminent end to the war, and preparing for a re-unification of the nation, President Lincoln urged the Republican Party's leadership to drop his previous vice-president, Hannibal Hamlin, an ardent abolitionist from Maine, in favor of Johnson, a Southerner and a Democrat. President Lincoln defeated General George McClellan in the 1864 election, and Johnson became vice-president of the United States of America.

Johnson took the oath of office in March 1865. The following month President Lincoln went to Ford's Theater in Washington for an e

vening of entertainment and was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Booth was part of a larger conspiracy to assassinate key members of the government. Andrew Johnson was a target of the conspiring assassins, but the assassin charged with killing the vice-president lost heart and did not attempt the assassination. Johnson became president on April 15, 1865.

The debate about Johnson's role in Reconstruction is highly charged, and much ink has been spilled attempting to disentangle the truth from the rhetorical flourishes that have grown up around the debate. A cursory examination of Johnson's actions in the post war period is likely to be both contentious and simplistic. What can be made clear is that early on in his administration, Johnson found himself at loggerheads with both the Congress and members of his cabinet. Whatever his own sympathies and motivations may have been, there were many in the government who opposed many of his actions, and several legislative measures were passed in spite of a Presidential veto.

Within his own administration, too, Johnson encountered resistance. Johnson attempted to dismiss Edwin Stanton, Lincoln's Secretary of War (and one of Johnson's fiercest critics), in 1868, but Stanton claimed that Johnson acted in violation of the Tenure of Office Act enacted the previous year. This act stated the president may not dismiss certain publicly elected officers without the consent of the Senate. Johnson vetoed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, but Congress voted the act into law over the president's veto. Stanton barricaded himself in his office, and Congress voted to impeach Johnson. Eleven charges were brought against President Johnson primarily dealing with violations of the Tenure of Office Act. Only three of these charges were voted upon, and these failed by one vote each of reaching the two-thirds majority required for impeachment. Upon Johnson's acquittal, Edwin Stanton left his barricaded office and resigned.

Johnson's presidency, though a turbulent one, began the reunification for a country suffering from four years of civil war. Under Johnson's administration the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery and the 14th Amendment providing for equal protection by law of all citizens were added to the Constitution. Johnson's presidency saw the addition of Nebraska to the United States and the purchase of the Alaska territory. Andrew Johnson completed the remainder of Abraham Lincoln's term of office but failed to receive his party's nomination in 1869.

Johnson returned to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he remained active in politics. He returned to public office in 1875 winning election to the U.S. Senate, but later that same year Andrew Johnson suffered a stroke and soon died. The seventeenth president of the United States was laid to rest on his land in Greeneville, Tennessee. Johnson requested that his body be wrapped in an American flag and laid on a copy of the Constitution. This request summarizes the man well. Born of humble origins in North Carolina's capital city, Johnson always supported the rights of the working class. He maintained a strong love of the Constitution and the federal Union it embodied. He willingly supported the Union cause, rejecting the actions of his home state.

Andrew Johnson's life and career show him to have been a man of great courage and integrity. He remained constant to his beliefs regardless of the personal cost to himself. Johnson's courage, dedication, and service to the nation in a difficult time of national transition reflect positively on Andrew Johnson and reflect well on his origins in the Old North State.

The preceding information was compiled from various sources (including the information pamphlet published by the Office of Archives and History for the Andrew Johnson birthplace at Mordecai Historic Park) by the Information Services Branch of the State Library.