29 Dec. 1808–31 July 1875

See also: Johnson, Andrew, from SLNC Government and Heritage Library

Andrew Johnson, seventeenth president, was born in Raleigh, the son of Jacob Johnson and Mary McDonough, yeomen. His first decades remain obscure. James Russell Lowell wondered that "a great unknown" could father such an offspring; others speculated that he was "the living spit" of a Haywood. A Raleigh lady recalled that "my old Grandfather . . . sent his Coachman to whip him & his cousins . . . back to their cabin because they had a fancy to run naked on the road." That this tailor's apprentice decamped is of record. In his romantic past lie peregrinations in South Carolina and Tennessee before he settled at Greeneville, Tenn., in 1826. Johnson found the new environment congenial; within a decade he had married, prospered, and entered politics. His wife, Eliza McCardle (daughter of John and Sarah Phillips McCardle of Greeneville), bore five children, the last in 1852. Johnson the tailor was also a petty capitalist, exchanging goods and services; moreover, he acquired town property and made small loans. In a material sense, he exorcised "the grim and haggard monster" of poverty; in his mind, never.

Allegedly, when the mechanic-politician became alderman and mayor, "the tailor shop crowd" challenged the local aristocracy; yet Johnson was no pariah when elected representative to the state legislature in 1835. Hesitant amid uncertain party affiliations, he was before his service closed (house, 1835–37; senate, 1839–43) a staunch Jeffersonian—regular in voting, the foe of internal improvements, one of the obstructionist "Immortal Thirteen." He displayed radical democracy and sectionalism, advocating a "white basis" for congressional representation and sponsoring a "State of Franklin" to be created from East Tennessee and neighboring areas.

But overwhelming ambition could not rest; and Johnson, eyeing Congress, purportedly gerrymandered the First Tennessee District. For five terms (1843–53) he remained invincible, in great measure because of his political acumen. Possessing a genius for sensing the popular whim, this feared stump speaker stood forth as a doughty plebeian, champion of the common man, while casting opponents as nabobs, mouthpieces for the vested interests. In Congress he exhibited many lifelong characteristics. A loyal Democrat, he was not invariably a party man; sectionalist, but not necessarily southern ; states' righter, but defender of the Union and the Constitution. Embracing such party shibboleths as low tariff, expansionism, and war with Mexico, he feuded with the leadership, notably with President James Knox Polk. Clashing with Jefferson Davis, he arraigned "an illegitimate, swaggering, bastard, scrub aristocracy." The tribune of the plebs labored for a homestead measure and popular election of the president and senators. The apostle of retrenchment opposed the Smithsonian Institution.

Virtually unknown nationally outside the House, Johnson was too well known in Tennessee, where Democrats wearied of his sinecure and Whigs "Henry-mandered" his district. He was on Golgotha. "My political garments have been divided and upon my vesture do they intend to cast lots"—a gloomy forecast for a decade which saw him in statehouse and Senate. Elected governor in 1853 and again in 1855, he vanquished such orators as the Whig Gustavus A. Henry and the "apostate" Meredith P. Gentry; in each close race he lost East Tennessee and won via the rural Middle Tennessee counties. The "radical" Johnson surfaced in a first inaugural which likened democracy unto a political ladder akin to Jacob's and envisioned "Democracy progressive" and the "Church Militant" converging towards theocracy.

Except for progress in public education, his governorship was undistinguished. Campaigns against internal improvements and the Bank of Tennessee failed; the assembly rejected his democratic constitutional "andyjohnsonisms." Not only had he assumed office inadequately prepared; not only did Governor Johnson, like President Johnson, lack effective liaison with the legislature; but the office was inherently weak, possessing neither patronage nor veto power. Yet, to the discomfiture of his opponents, he remained "the king of the Democracy." By 1856, the king dreamed of the vice-presidency or even the White House; but presently, Capitol Hill would suffice.

Chosen senator on the first ballot, Johnson returned to discord. When he had departed Washington in 1853, the sectional dilemma appeared solved; four years later, compromise had been aborted. The Tennessean did not immediately enter the vitriolic debate over slavery, considering it "in perfect harmony" with democracy and himself enslaving several people as "household" servants and workers. Instead, he concentrated on the homestead, presenting in May 1858 a rambling and discursive manifesto. By 1860 the measure, now espoused by Republicans and tolerated by proslavery men, passed only to be vetoed by James Buchanan. Meanwhile Johnson plunged into presidential politics, standing as a dark horse at Charleston; disappointed, and looking to 1864, he gave the Breckinridge ticket lukewarm support.

Swept up in the great denouement, the senator emerged as a national figure acclaimed by Unionists everywhere. In a ringing speech on 18–19 Dec. 1860, he denied the constitutionality of secession and urged defense of Southern rights within the Union; subsequently he denounced treason and conspiracy. In Tennessee, ironically, the "traitor" found himself divorced from democracy and consorting with Whiggery; his state seceded, the "martyr" stumped Kentucky and Ohio. He became an influential member of the Radical-dominated Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Johnson's unstinting patriotism brought appointment to the Tennessee governorship in February 1862. To an unprecedented Eng/Chang mission implicit in the Siamese "brigadier general and military governor" charged with restoring loyalty and civil government, he carried both assets and liabilities. It was an Augean task: refractory aristocrats and evasive "hermaphrodites," secesh parsons and pouting women, Graybacks and guerrillas, contentious generals and subalterns, matters great and small. Loyalty and restoration must await military supremacy. Called imaginatively "his finest hour," the governorship was more nearly a study in perseverance. And yet it enhanced his political fortunes. His steadfast courage, his brutum fulmen—"treason must be made odious and traitors impoverished" —his "radical" espousal of abolition, his "availability" as War Democrat; these, with Lincoln's confidence and Republican approbation, propelled him into the vice-presidency. Assassination completed a progression.

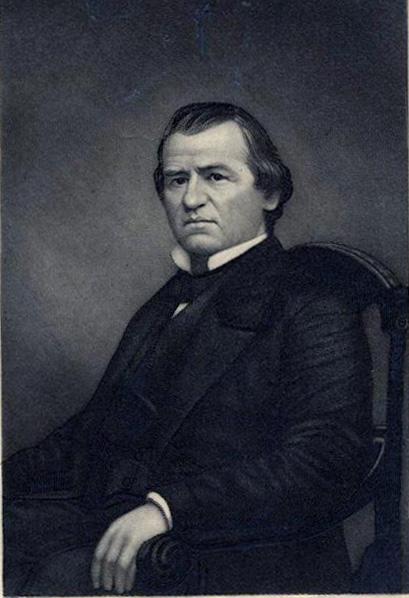

What of the tailor become hierarch? For one past "the meridian of life," the president radiated vigor and purpose. Of medium height and sturdy frame, dark eyes and graying hair, he wore an expression that prompted a sobriquet "the Grim Presence." The frock coat and accoutrements, an estate that reached $110,000 in 1870, and a continuing self-education—though his speeches ne'er rang in runic rhyme—testified to his climb up Jacob's ladder. Fundamentally Johnson remained unchanged: a loner with few intimates, a champion of the underdog and an enemy of privilege, a shrewd, calculating politician, a man with a persecution complex, and a moralist whose mind contained "one compartment for right and one for wrong" but no middle chamber between. This Algerian figure now faced his sternest test.

Reconstruction theories ranged from "forgive and forget" to Carthaginian peace; to those of the latter persuasion, Johnson seemed an avenging angel. "By the gods, there will be no trouble now in running this government," proclaimed Benjamin Wade. In reality this Catonian image widely credited North and South was a distortion. Despite proscription of "high" and "propertied" Confederates, his program, initiated between Congresses, was surprisingly lenient. Why the volte-face? Perhaps it reflected a stocktaking. Johnson discriminated between leaders and followers; intended that the South remain a white man's country; saw planter bloc replaced by Northern plutocracy; and, fatally stricken with the presidential virus, possibly contemplated a common man's democracy. Undoubtedly he had moderate counsel from the Sewards and the Blairs, and from Southerners.

Still, Reconstruction was not tunnel but labyrinth. Not all Northerners would forgive and forget; Congress, jealous of executive power, would reassert prerogative. Whether moderate, radical, or conservative, legislators generally believed they should preside over Reconstruction. And those Southerners—ex-Confederates in government, an apparently unreconstructed press, freedmen relegated to de facto slavery—were they loyal?

Another chapter in a historic tug-of-war had begun. Despite congressional exclusion of Southern representatives and creation of a Joint Committee on Reconstruction, the president remained optimistic. Early in 1866 he vetoed Freedmen's Bureau and Civil Rights bills; and, scenting victory, publicly identified Thaddeus Stevens and others as disunionists. Now sentiment swung against him, and in the ensuing year Congress passed over his veto such measures as the Fourteenth Amendment, the Tenure of Office Act, and the Military Reconstruction Act. His innovative midwestern "Swing around the Circle" during the congressional elections of 1866 was a disaster. Factors perhaps in toto irrepressible—among them his Tyler-like situation, his inflexibility and lack of congressional liaison, Southern mistakes, and Radical determination—defeated presidential Reconstruction.

Yet the drama had not ended; for Johnson, resisting the mandate by means open and sub rosa, added to the plot. Ouster had been bruited as early as 1866; and after his removal of Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton challenged the Tenure of Office Act, enemies—"Tray, Blanch, Sweetheart, little dogs and all," in Johnsonian parlance—procured in January 1868 impeachment for "high crimes and misdemeanors." The grand assize came in the spring, the Grim Presence comporting himself with dignity in absentia. In crucial roll calls which saw seven "recusant" Republicans side with the Democrats, conviction failed 35–19, one short of the necessary two-thirds. Interpretations of this crisis vary widely. Contemporaries often saw either Radical plot or just retribution. A legalistic approach stresses attack not only upon the man but also upon the presidency; a political persuasion contends that Johnson held a concept of office established only this century—thus, impeachment was a justifiable weapon against encroachment. These are converging polarities, each invoking checks and balances. Yen for power, high crimes, unindictable but impeachable—semantics and hypotheses redolent of Watergate—remind us that the historian is a creature of his or her times.

Scarcely Brownlow's "dead dog of the White House," Johnson was a lame duck not only for his term but also for another as well. Rejected by the democracy, his star descendant, he became per census "Ex Pres Retired"; yet, "Retired" to stage his own encore, this time for vindication. Again there was the strain of antimonopoly: let the public debt be repudiated! Again there was the Johnson mantra—no longer so binding. Losing Senate and House bids in 1869 and 1872, he was elected senator in January 1875. For one bittersweet month, a special session in March, he returned, the only former president to do so, and delivered a philippic against the incumbent Ulysses Grant. It was his envoi. Having survived facial tumor and cholera epidemic, he died of a stroke in Carter County, Tenn., and was interred in Greeneville.

In all likelihood the Johnson stereotype will persist: racist demagogue, vindictive and inflexible, power his compelling goal; man of the people, patriot and statesman "slandered and vilified by the press and the biased historians"—admixture of truth and falsehood. Ironically the realities, like the images, seem contradictory. Highly successful in many ways, Johnson always felt the sting of "huckletooth": of poverty, exclusion, obloquy, even of hatred. He suffered from a basic insecurity; hence his perennial war against "the interests," whether unskilled labor, slavocracy, or emerging financial-industrial combination. In this populist and freesoiler, radical and conservative commingle; in his career, one senses the clash of old and new. Was not the erstwhile tailor spokesman for a little America of limited government and equal opportunity, an America "of the people"? In the "implacable and unforgiving" Johnson, one detects a strong sense of lenience, a receptiveness to flattery, a vulnerability to the feminine sex. In his simplistic view of life but also in his complexities, the compleat Andrew Johnson symbolizes the nineteenth century.