17 June 1742–14 Oct. 1790

William Hooper, one of North Carolina's three signers of the Declaration of Independence, foremost Patriot leader, writer, orator, attorney, and legislator, was the oldest of five children of the Scots divine, the Reverend William Hooper (1704–14 Apr. 1767), second rector of Trinity Episcopal Church, Boston, Mass., and Mary Dennie Hooper (b. ca. 1720), daughter of Boston merchant John Dennie. He was the grandson of Robert and Mary Jaffray Hooper of the Parish of Ednam, near Kelso, Scotland. It should be noted that William Hooper's blackened sandstone slab in Hillsborough, N.C.'s Old Town Cemetery carries the New Style or Gregorian calendar birthdate, 28 June 1742, eleven days later than the Old Style or Julian calendar date, 17 June 1742, used in the published accounts of Hooper. The slab is thought to have been placed between 1812 and 1818 by the Signer's only daughter and surviving child, Elizabeth (Mrs. Henry Hyrn Watters), who evidently preferred the New Style date. An unusually delicate, nervous child, William was at first painstakingly taught at home by his father, himself a classicist and orator of some note, educated at the University of Edinburgh. At age eight, the boy was sent to the Boston Public Latin School where he worked so hard under headmaster John Lovell, a celebrated disciplinarian and staunch Loyalist, that at fifteen he entered the sophomore class of Harvard College on 7 Oct. 1757. He was graduated A.B. in 1760 with marked distinction in oratory, surpassing, it is said, even his father in that field.

Although the Reverend Mr. Hooper had hoped that his oldest son and namesake would enter the ministry, William's own inclination led him to law; and in 1761 his father allowed him to study under the brilliant James Otis, famed for his knowledge of common, civil, and admiralty law. Various Hooper biographers have stated that Otis's fiery stands for colonial rights indoctrinated the young Hooper.

In 1763 Harvard College conferred an M.A. on Hooper, and in 1764 he settled temporarily in Wilmington, N.C., to begin the practice of law. Hooper, who was handsome, well-bred and well-educated, with courtly manners and a pleasing personality, was warmly accepted by the planters and lawyers of the lower Cape Fear. By June 1766 he was unanimously elected recorder of the borough.

From the beginning, however, Hooper's health had been precarious in the low-lying Wilmington area. He was seriously considering leaving New Hanover County when his father died without warning one Sunday, "falling down suddenly in his garden." William's education was to be his chief inheritance, although his father's will also left to him "all my Books and Manuscripts," a legacy that he treasured. He apparently made a firm decision to continue his legal career so well begun in North Carolina and, on 16 Aug. 1767, married at King's Chapel in Boston Anne Clark, of New Hanover, the daughter of Barbara Murray and Thomas Clark, Sr., late high sheriff of New Hanover County. Anne was the sister of Thomas Clark, Jr., who became a colonel and brigadier general in the Continental Army. It was the fortunate affluence of the Clark family that enabled the William Hoopers to survive the difficult years of the American Revolution.

Hooper's legal work took him in every direction of the province; he traveled on horseback 150 miles and more to backcountry courts in all seasons and weather. In 1769 he was appointed deputy attorney general of the Salisbury District and inevitably ran afoul of the Regulators, incurring their lasting enmity. A 1768 incident in Anson County was followed by another at the Hillsborough riots of September 1770, when Hooper reportedly was dragged through the streets by the Regulators.

His formal entry into political life came on 25 Jan. 1773, when he sat for the first time in the Provincial Assembly as representative for the Scots settlement of Campbellton (later Fayetteville). The Assembly, meeting at New Bern, lasted only forty-two days, but Hooper became acquainted with such recognized provincial leaders as Samuel Johnston, Allen Jones, and John Harvey. In the same year, Hooper made the first purchase of land for his future home on Masonboro Sound eight miles below Wilmington—108 acres of Caleb Grainger's old Masonborough Plantation. In 1774 he bought 30 adjoining acres on which he built his house, Finian. The Hoopers offered lavish hospitality at Finian to guests from far and wide, and the sound provided pleasant surroundings for their three young children: William (b. 1768), Elizabeth ("Betsy") (b. 1770), and Thomas (b. ca. 1772).

In 1773 a new courts bill agitated the province, and Hooper threw all of his energy and talent into a campaign to defeat it, arguing that the bill meant further encroachment by the Crown on colonial rights. His influential "Hampden" essays, now lost, were written about this time to explain to the citizenry at large the critical issues involved and why the bill should be defeated. The upshot of the conflict was that most provincial courts were closed and that Hooper was disbarred from practicing law for a year.

In December 1773 he was returned to the Provincial Assembly as representative for New Hanover County together with John Ashe, leader of the Whig party. On 8 December the Assembly took the important step of appointing a standing Committee of Correspondence and Inquiry and selected nine of the most significant leaders in the province to serve on it. Hooper's was the fourth name listed, and it was on this committee of communication that he made signal contributions throughout the Revolutionary years. His prophetic observation in a letter of 26 Apr. 1774 to his friend James Iredell is often quoted as a landmark of colonial foresight at this early period. He wrote, "They [the colonies] are striding fast to independence, and ere long will build an empire upon the ruins of Great Britain; will adopt its Constitution, purged of its impurities, and from an experience of its defects, will guard against those evils which have wasted its vigor."

In June 1774 the port of Boston was closed, and Hooper took the lead in mustering aid and support for his native city. At a notable general meeting of lower Cape Fear citizens in Wilmington on 21 July, he was elected chairman and presided over the selection of a committee to issue the historic call for the First Provincial Congress. A significant resolve approved by the New Bern meeting stated, "We consider the cause of the Town of Boston as the common cause of British America, and as suffering in defense of the Rights of the Colonies in general." Two shiploads of provisions and £2,000 in currency were sent for the relief of the Massachusetts port town. Already the thirty-two-year-old Hooper's diverse talents for persuasive oratory and fluent writing plus his ardent, personal commitment to the colonial cause and his trained knowledge of civil and admiralty law had combined to make him a most useful and effective leader in any assembly in which he sat.

When the First Provincial Congress—the first such convention ever to meet without royal assent—duly convened in New Bern on 25–28 Aug. 1774, Hooper was named the first of three delegates to represent North Carolina at the First Continental Congress which met on 20 September at Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia. The other two envoys were Richard Caswell and Joseph Hewes. Although Hooper was one of the youngest of the fifty delegates in Philadelphia, he was immediately named to a committee "to state the rights of the colonies" and to another to report on legal statutes affecting trade and commerce in the colonies. "[Richard Henry] Lee, Patrick Henry, and Hooper are the orators of the Congress," wrote John Adams. Back in Wilmington, Hooper was named to the Wilmington Committee of Safety, formed on 23 Nov. 1774. He could not, however, be present until 30 December.

There now began the steady, physically exhausting cross-country travel by horseback between Philadelphia and North Carolina that Hooper continued until the spring of 1777. Nearly all of his work in both places followed the same routine: long days of committee sessions and staggering amounts of correspondence, reports, and addresses to be written at night. At Philadelphia there was the added burden of purchasing supplies at warehouses and wharves and dispatching them to Committees of Safety and militia at home. Moreover, yellow fever in Philadelphia and malaria in Wilmington were constant hazards.

Before the close of 1776, Hooper had attended three Continental Congresses, four Provincial Congresses (he did not attend the fifth in Halifax in November 1776 because of the pressure of work in Philadelphia), and four Provincial Assemblies besides meetings of the Wilmington Committee of Safety. Almost invariably he was made chairman or member of any committee with important resolutions or addresses to compose, and some of the most significant statements of the Revolution crystallizing public opinion came either wholly or partially from his pen.

At the lengthy Third Provincial Congress (20 Aug.–10 Sept. 1775), which met for safety's sake far inland at Hillsborough, Hooper was made chairman of a committee to prepare a Test Oath for the 184 delegates. Since the Battle of Lexington on 19 April, tension and alarm had been rampant. Hooper was appointed to a committee to prepare an explanatory address to the people of North Carolina and named chairman of another to prepare an address to the "inhabitants of the British Empire." Hooper alone composed the important British Empire address declaring the views of the Congress on the existing state of affairs. Besides other assignments, he was also one of a committee of 45 delegates to devise a temporary government for the province.

About 1 Feb. 1776 Hooper quietly absented himself from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia to go to his widowed mother's aid in Cambridge, Mass. According to Joseph Hewes, Mrs. Hooper had only "lately got out of Boston," and her Patriot son was greatly alarmed for her safety. Still absent from Philadelphia a month later, Hooper may have seized this opportunity to escort his mother to Milton, N.C., where she is said to have spent her later years. Her death date is unknown.

The Fourth Provincial Congress convened at Halifax on 4 Apr. 1776, and Hooper and John Penn (who had replaced Caswell) appeared on 15 April, three days after the passage of the Halifax Resolves. Hooper was immediately made chairman of a committee to supply the province with ammunition and "warlike stores," and he and Penn were added to a committee to produce a civil constitution and to another on secrecy, war, and intelligence. Both men were placed on committees to consider business necessary to be brought before the Congress and to form a temporary government, as well as on a committee of inquiry. Hooper, Hewes, and Penn were all reappointed delegates to the Third Continental Congress which convened on 10 May 1776.

In Philadelphia Hooper served on Hewes's marine committee; with Benjamin Franklin on the highly important committee of secret intelligence which had broad powers to hire secret agents abroad, make agreements, and even to conceal information from the Congress itself; and on John Adams' Board of War committee. Although Hooper was absent when independence was actually voted and declared on 4 July 1776, he, like most of the other delegates, affixed his name to the amended Declaration on 2 August.

For the rest of the year Hooper was concerned with committees for the regulation of the post office, the treasury, secret correspondence, admiralty courts, laws of capture, and the like. On 22 December he was appointed chairman of a committee with Hewes and Thomas Burke to devise a Great Seal for the new state of North Carolina.

Early in 1777, Hooper and numerous other delegates were stricken with yellow fever. On 4 February he secured permission to return to Wilmington to attend the General Assembly on 8 April, and on 29 April he formally resigned his seat in the U.S. Congress. "The situation of my own private affairs . . . did not leave me a moment in suspense whether I should decline the honour intended me," he wrote to Robert Morris. He was succeeded by Cornelius Harnett and never again appeared on the national scene.

Hooper resumed his residence at Finian and his law practice in the newly opened courts, again riding the circuits with his friend Iredell as he had done before the Revolution. He attended the General Assembly of 1777, 1778, 1779, 1780, and 1781 as member for the borough of Wilmington, serving on numerous committees. When it appeared that Finian would not be safe from British men-of-war in Masonboro Sound (a house owned by Hooper three miles below Wilmington was burned and Finian was shelled), Hooper moved his family into the town. He himself, at times seriously ill with malaria and his right arm badly swollen, became a fugitive from the British, going from friend's house to friend's house in the Windsor-Edenton area.

On 29 Jan. 1781 Major James H. Craig's men took Wilmington, although the town was not evacuated until November. Then, an ailing Mrs. Hooper and two of her children were forced to flee by wagon to Hillsborough where her brother, General Clark, found shelter for them. Finally, on 10 Apr. 1782, the reunited Hoopers purchased General Francis Nash's former home on West Tryon Street (still standing and in 1972 named a National Historic Landmark). Hooper's preserved Memorandum Book, 1780–1783 provides valuable records of this period.

With his permanent removal to the backcountry, Hooper was now entirely out of the mainstream of current events, both state and national. His election to the 1782 General Assembly as member for Wilmington was declared invalid, and in 1783 he suffered the first political loss of his career at the hands of Hillsborough tavern keeper Thomas Farmer, who defeated him for a seat in the General Assembly. One absorbing new interest developed, however. Some years before, in 1778, Hooper had been named first on a committee of nine prominent men to begin an academy, "Science Hall," in the vicinity of Hillsborough. The school had made a brave start on Colonel Thomas Hart's Hartford Plantation, but it had been swept aside by Revolutionary activity. Now, Hooper pushed a new academy bill through the 1784 Assembly, to which he was elected, and almost single-handedly began a second venture, a new "Hillsborough Academy," which prospered for a few years. Unfortunately, the November 1786 Assembly at Fayetteville, the last that he attended, tabled a bill to raise funds for the school and thereby ensured its demise.

Hooper's law practice was still a considerable one owing to steady litigation concerning Loyalists' estates, confiscated lands, treason, and all the legal backwash of the Revolution. Like Iredell and other conservative men, Hooper lamented unreasonable severity and vengefulness against Loyalists and absentees and urged moderation in their treatment. In consequence, he found himself at painful odds with some of his old friends and acquaintances. On 22 Sept. 1786 he was appointed to a federal court to settle a Massachusetts–New York territorial dispute, but the matter was resolved locally and the court never met.

A bitter blow fell when Hooper was not elected a delegate to the 1788 Constitutional Convention, which met in Hillsborough's old St. Matthew's Church (then renovated as the new academy), literally within sight and sound of his own house. He never recovered from this second important rejection. The Iredell correspondence indicates that from 1787 onward there had been a perceptible decline in Hooper's health and that, like his fellow townsman, Thomas Burke, he had chosen to drown his increasing disillusionment in rum. He died at age forty-eight, the evening before his daughter Elizabeth's marriage to Colonel Henry Hyrn Watters of the Cape Fear.

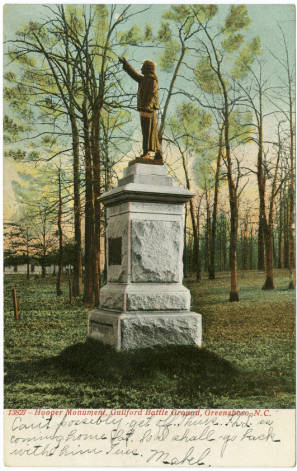

Hooper was buried in a corner of his garden, and the brick-walled plot was later incorporated into the adjoining Old Town Cemetery. On 25 Apr. 1894, the grave was opened at dawn before various family representatives, and a very few discernible relics—part of a button and a nail or two—were placed in an envelope and removed, together with the covering sandstone slab, to the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Greensboro. There an imposing 19-foot-high monument, surmounted by a statue of Hooper in colonial dress and in orator's pose, honors the patriotic services of William Hooper and his friend and colleague, John Penn. The sandstone slab, with six additional words deeply incised, "Signer of the Declaration of Independence," was later returned to the original Hillsborough grave site.

Hooper's portrait was painted in 1873 by the prominent Philadelphia artist, James Reid Lambdin (1807–89), who was commissioned by the Committee on the Restoration of Independence Hall. Lambdin's portrait copied the head of William Hooper in John Trumbull's (1756–1843) study for his famous painting, The Signing of the Declaration of Independence. It remains uncertain, however, whether Trumbull actually painted Hooper from life. In February 1790 Trumbull traveled to Charleston, S.C., to collect likenesses of the Signers, but it seems unlikely that Hooper's swiftly deteriorating condition at that date would have permitted even short sittings for a sketch.