6 May 1740–14 Sept. 1788

John Penn, revolutionary statesman and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was born near Port Royal in Caroline County, Va., the only son of Moses and Catherine Taylor Penn. Moses Penn did not place a high priority on formal education, so his son received only a few years of instruction at a local school. When John was eighteen, his father died, leaving him a comfortable estate. Thereafter, Edmund Pendleton, young Penn's kinsman and neighbor, offered him the use of his library. Penn studied law under Pendleton's guidance and at age twenty-one was admitted to the bar in Caroline County, where he practiced law for the next twelve years.

Penn married Susannah Lyme of Granville County, N.C., on 28 July 1763. No doubt family ties influenced the Penns' move to North Carolina in 1774. John Penn purchased a farm in the northern part of Granville County near present Stovall. The following year he was elected to the Third Provincial Congress, which met at Hillsborough on 20 Aug. 1775. An active member of the Congress, Penn was elected to succeed Richard Caswell as delegate to the Continental Congress; Caswell had resigned to become the treasurer for the Southern District of North Carolina. The original congressional delegation (William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, and Richard Caswell) were all easterners who had supported Governor William Tryon against the Regulators. Penn's election was clearly an attempt to appease backcountry leaders like Penn's neighbor and political supporter, Thomas Person. Although Penn frequently disagreed with Hooper and Hewes on political questions, he shared their hope for reconciliation with Great Britain. Penn was the first of the three to favor independence. Writing to Thomas Person on 14 Feb. 1776, he advocated foreign alliances even if the consequence was total separation from the mother country. By March all three delegates believed that independence was inevitable.

Penn and Hooper returned to North Carolina to attend the Fourth Provincial Congress at Halifax and to receive instructions. They arrived in Halifax on 15 April, three days after the Congress had voted to instruct their Continental delegates to vote for independence. Penn was reelected to the Continental Congress but remained in Halifax until the Provincial Congress adjourned. He returned to Philadelphia in June and with Hewes cast North Carolina's vote for independence on 2 July.

In December 1776 the Fifth Provincial Congress appointed Thomas Burke to Penn's seat in the Continental Congress. But when the first Assembly under the new state constitution met the following April, Penn, who was a member of the lower house, won the seat held by Joseph Hewes. The bitterly contested election was influenced by charges that Hewes, an Edenton merchant, had been neglecting his congressional duties to engage in a profitable trade as commissioned agent of the Congress's Secret Committee.

Although Penn never attained prominence as a member of the Continental Congress, he attended the proceedings for 1,038 days, longer than any other North Carolina delegate during the Revolutionary War, and served on fourteen committees and eight standing boards. Believing that a permanent union was necessary, he signed the Articles of Confederation on 16 July 1778. Along with the other North Carolina delegates he consistently voted with the southern bloc.

Criticism that Penn neglected his congressional duties seems on the whole unjustified. The correspondence of the North Carolina delegates who served with him provides no basis for the charge beyond a December 1778 letter from Thomas Burke to Governor Richard Caswell describing the "gaiety and Dissipation, public Assemblies every fortnight and private Balls every night." Burke concluded, "In all such business as this we propose that Mr. Penn shall represent the whole state." In 1779 Henry Laurens challenged Penn to a duel. As he assisted the elderly Laurens across a street on the way to the dueling ground, Penn proposed that their plans be abandoned. Laurens agreed but continued to disdain Penn's politics and abilities. Later that year Charles Thomson, secretary of the Congress, reported that Laurens answered Penn in debate singing, "Poor little Penny Poor little Penny."

The British victory at Camden on 16 Aug. 1780 paved the way for invasion of North Carolina. The military threat led to a crisis in government. The constitution did not provide the governor with adequate emergency power, and at Governor Abner Nash's request the Assembly created a three-man Board of War with control of military affairs consisting of Penn, Colonel Alexander Martin, and Oroondates Davis. They met at Hillsborough in September 1780. Since the other two members were absent during most of the board's four-month existence, Penn acted alone much of the time. The board was primarily involved in equipping and supplying the North Carolina militia and General Nathanael Greene's army operating in North Carolina; it provided energetic leadership during the crisis, coordinating military activities and securing provisions and transporting them to the armies. The Assembly abolished the board in January 1781 after complaints from military officers who resented civilian interference with military affairs and from Governor Nash, who claimed that the board had usurped his authority.

Five months later Penn was elected to the governor's Council. He was president of the Council during the closing months of the war, when the Council met frequently with Governor Thomas Burke. After two years on the Council Penn was defeated for reelection in 1783. The following year Robert Morris appointed him receiver of taxes for the Confederation in North Carolina, but Penn resigned the office within a month of his appointment.

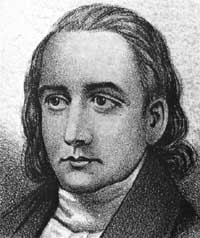

Penn was buried at his home near Island Creek in Granville County. In 1894 his remains were reinterred at Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. Two children, William and Lucy, survived. An etching of John Penn by H. B. Hall is in the Emmet Collection, New York Public Library.