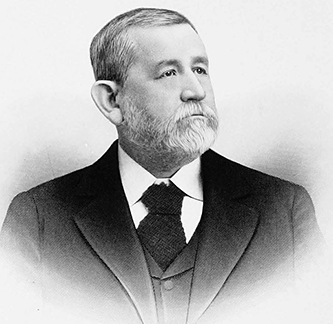

21 Apr. 1832–8 June 1908

David Moffatt Furches, lawyer, jurist, and chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, was born in Davie County, the son of Stephen Lewis Furches, a justice of the peace and farmer, and Polly Howell Furches of Rowan County. The Furches family was originally from Delaware. Young Furches attended the Union Academy in Davie County before studying law for two years under Richmond Pearson, the noted chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court. Admitted to the bar in 1857, Furches began his law practice as solicitor for Davie County in Mocksville, where he remained until 1866 when he moved to Statesville in Iredell County. When the Civil War broke out, Furches joined the Confederate Army for a short time, even though as a county solicitor, he was exempt from military service. However, his three brothers and four brothers-in-law served, and, as Furches put it, he "concluded to stay out."

A sturdy Whig before the war, Furches served as a Davie County delegate to the Constitutional Convention that met in Raleigh in October 1865. Following the guidelines announced by President Andrew Johnson, that convention adopted ordinances abolishing slavery, abrogating the secession act, and repudiating the Confederate debt. During Reconstruction, Furches's Whiggery and Unionism led him into the Republican party. As a Republican, he waged a number of futile campaigns for office. In 1872 he was defeated in a bid for Congress, but in 1875 he was appointed judge of the superior court in Iredell County and served for three years. In 1880 he made another unsuccessful run for Congress. When the North Carolina Republican party nominated him for associate justice of the state supreme court in 1888, he was again defeated.

Disillusioned and disheartened by an unending string of defeats since Reconstruction, the Republican party in North Carolina had become badly factionalized by the 1890s. One wing of the party, resenting Black aspirations for local party leadership and fearing the Democratic use of the race issue, opposed a statewide ticket and leaned toward cooperation with the newly established Populist party. The Old Guard, however, continued to insist on a full slate of candidates and objected bitterly to any association with the Populists. In 1892 Furches was the Republican candidate for governor, although the lily-white faction of the party had threatened to support the Populists. When he lost the election, Furches charged that the "true theory of Republican defeat in North Carolina was fraud." According to him, the Democratic registrars had prevented many Black citizens from voting. Furches's claims notwithstanding, there is considerable evidence that many Republicans defected to the Populist cause.

In 1894 Furches, whom Josephus Daniels once termed a Republican of the "old order," again supported efforts for a full Republican slate and opposed cooperation, or "Fusion" as it was known, with the Populists. Demanding a straight Republican ticket, Furches argued that the Republican party could not be transferred like cattle from one field to another. But the Populists shrewdly nominated a nonpartisan judicial ticket that included Furches, the Republicans accepted the coalition ticket, and the Fusionists swept into office. As a result, Furches became an associate justice on the state supreme court.

Furches's career on the North Carolina Supreme Court was marked by the same acrimony and controversy that characterized the politics of the period. His elevation to the chief justiceship was not without its share of intrigue. In December 1900 Chief Justice William T. Faircloth died a mere two weeks before the inauguration of Democrat Charles B. Aycock as governor. Republican Governor Daniel L. Russell came under intense pressure from various interest groups to resign his office and accept appointment to the chief justiceship from the lieutenant governor who would succeed him. Corporate titans such as Alexander B. Andrews, vice-president of the Southern Railway Company, and Benjamin N. Duke, the Durham tobacco magnate, urged Russell to pursue that course. Many Democrats such as Robert Furman, editor of the Raleigh Morning Post, and Robert B. Glenn, future governor, applauded the idea because it was widely believed that Russell supported the recently adopted suffrage amendment disfranchising Black North Carolinians. Russell, however, resisted the pressures and in a surprising move appointed Furches chief justice. The governor and the supreme court justice had been feuding since the 1892 election when Russell, a leading Fusionist, had refused to support Furches's candidacy for governor.

Furches barely had assumed the chief justiceship when he was impeached by the Democratic-controlled General Assembly of 1901. Political passions had been inflamed dangerously by the Democratic white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900 that overturned Fusionist rule. Eager to regain control of the state courts, zealous Democrats in the legislature, urged on by Josephus Daniels's "tocsin-sounding" Raleigh News and Observer, plotted the impeachment and conviction of Republican justices David Furches and Robert M. Douglas. Conservative Democrats like Henry G. Connor and Thomas J. Jarvis, the former governor and senator, were appalled. Jarvis wrote Connor: "It will be a great mistake in our party to put these Judges on trial. It is hard to conceive of a worse political error." Jarvis did not believe that Furches and Douglas had acted "corruptly," although they may have made legal mistakes. Some Democrats, Jarvis confided, insisted on impeachment "to save the Constitutional Amendment." Connor, agreeing with Jarvis, led the fight against impeachment in the General Assembly.

The crux of the impeachment articles against Furches and Douglas related to the state supreme court's ruling that the holder of a public office had a property right in that office. So long as the duties of that office continued, the officeholder could not be deprived of his property during his term of office. Furches and Douglas were charged with violating the state constitution by issuing a mandamus against the state auditor and state treasurer in 1900 to compel payment of the salary of Theophilus White, a shell fish commissioner and a Fusionist, whose office had been abolished by the 1899 legislature. The duties of the office had been vested in a seven-member commission.

The precedent for office as property had been set in Hoke v. Henderson (1833). In 1897 the supreme court had upheld that precedent in the state hospital cases—notably Wood v. Bellamy and Lusk v. Sawyer —the effect of which was to continue in office Democrats and to prevent Fusionists from assuming control of state institutions. The court, though dominated by three Republicans and one Populist, had voted unanimously in those cases. In later cases arising in 1899, however, justices Walter Clark, the Progressive Democrat, and Walter Montgomery, the Populist, had rejected the Hoke v. Henderson precedent even though the Republican majority, consisting of Faircloth, Furches, and Douglas, continued to uphold it. Thus, the supreme court ruled in White v. Hill and White v. the Auditor that the office of shell fish commissioner had not been abolished by the 1899 legislature because the same duties still resided with the new commission. According to the Republican majority on the court, White was entitled to serve the last two years of his term and receive proper compensation as stipulated by the mandamus. Justice Clark lodged a vigorous protest and warned that any state officials executing the mandamus might be subject to impeachment as the court had not voted unanimously for the measure.

Despite the objections of Henry Connor, the house passed the articles of impeachment and a senate trial, lasting seventeen days, commenced. The key to the prosecution's case was whether the mandamus that ordered the payment of White's salary came within the constitution's definition of a "claim against the State." The senate, refusing to convict the justices, acquitted them of all charges. Fabius H. Busbee, a counsel for the respondents in the senate trial, declared afterwards that "the impeachment was political prosecution and instituted to prevent apprehended dangers, rather than to punish past offenses." Connor, who was elected to the supreme court in 1902, had the privilege of writing the opinion in the case of Mial v. Ellington (1903), which overruled the precedent of Hoke v. Henderson.

Furches's term expired in 1903, and he returned to Statesville to practice law in the firm of Furches, Coble, and Nicholson. Although he was married twice—to Eliza Bingham and Lula Corpening—he had no children. Furches was a member of the Episcopal church.