3 July 1852–23 Nov. 1924

Henry Groves Connor, judge, was born in Wilmington, where his parents, David and Mary Catherine Groves Connor, had moved from their native Florida. In 1855, David Connor, a carpenter described as a "master craftsman in woodworking," moved with his family to Wilson to work on the construction of a new county courthouse. He died there in 1867, leaving his widow with married daughters and several school-age children. The son, Henry Groves, who was always called Groves by his family and friends, left school to support himself and assist his mother and her younger children. He went first to Tarboro to clerk in a store, planning a career in merchandising, but soon, probably through the influence of George Howard of Tarboro, returned to Wilson as clerk and student of law in the office of George W. Whitfield, who was associated in practice with Howard. Whitfield died in 1871, but for the remainder of his life, Howard was one of Connor's closest friends.

Connor completed his legal education by a few months of concentrated study with William T. Dortch of Goldsboro and received his license in 1871 at the age of nineteen. It was later said of him that the only rule he ever broke was the one requiring a practicing lawyer to be twenty-one years of age. In the same year he married Whitfield's daughter Katherine and established a home in Wilson for her, his mother, and a younger sister. In the meantime he had left the Roman Catholic church of his parents to affiliate with the Protestant Episcopal church, which was also that of his wife; the couple became and remained staunch members of St. Timothy's Episcopal Church in Wilson. In 1872 the Connors had a son, the first of twelve children, nine of whom lived to maturity. Connor was a devoted husband and father, and he and his wife shared a long and compatible marriage, dying in the same year.

Early responsibilities made the young man seem older than his years, and his personality, industry, and character soon won for him the respect and regard of his community. He became known as a hard-working and competent lawyer and in 1877 established a partnership with Frederick A. Woodard. His local political popularity was injured by his support of the Prohibition movement, and for several years he was content to work within the Democratic party without seeking office. In 1884 he ran for a seat in the North Carolina Senate as a Cleveland Democrat and was elected to represent the district of Wilson, Nash, and Franklin counties.

In spite of youth and legislative inexperience, Connor was appointed in the senate of 1885 chairman of the Judiciary Committee, a position of great prestige. His most significant service as a senator was his successful sponsorship of the Connor Act, requiring the registration of deeds and thus contributing greatly to the stabilization of land titles in the state.

Connor's contemporaries recognized that he was more interested in professional than in political advancement, and after the creation of additional superior court districts in 1885, on the recommendation of a joint legislative committee of which he was not a member, he was appointed by the governor to one of the new positions. At the next election in 1886 he was elected to the court for a term of eight years; he became widely known as a judge of ability and humanity. His popularity in his community grew to such an extent that when his home burned in 1888, at a time when temporary financial hardship had caused him to allow his insurance to lapse, his neighbors and friends provided the funds to rebuild it.

In 1893 the needs of his growing family caused Connor to resign his position on the bench and return to private practice in order to increase his income and have more time at home. As one of the coexecutors of the estate of Alpheus Branch, founder of the private Branch Banking Company of Wilson, he became closely associated with the legal affairs of the bank; in 1896, on the death of his coexecutor, he became bank president. This was not for him a full-time position, and he continued his other activities while serving until 1907 as nominal president of the bank.

Although Connor was a firm Democrat, in 1894 he was nominated for a position on the North Carolina Supreme Court by the Populist party. He later wrote that it was the aspiration of his life to serve on the court, but he refused to run as the candidate of the Populists and was so embarrassed by their nomination that he also declined to seek the support of his own party.

When the Democrats lost control of the state as a result of the fusion of Republicans and Populists in 1896, Connor accepted his party's view that the safety and well-being of North Carolina required the return of the Democrats to power. He was an active participant in the campaign of 1898 led by his friend Charles B. Aycock, although he deplored the strong appeal to racial prejudice that marked the campaign. He was elected a representative of Wilson County to the North Carolina House of Representatives, and with Aycock's endorsement received the unusual honor of being chosen speaker in his first term in the house. He was thus a leader in the General Assembly that drafted the constitutional amendment establishing an educational qualification for voting, at the same time protecting the votes of illiterate whites by a "grandfather" clause. Connor's views of suffrage were those of his race and generation, but he was anxious that any restrictions be established openly and constitutionally, and one of his primary motivations was to secure honest elections.

After the adoption of the amendment, Connor was again elected to the legislature in a campaign that returned the state to Democratic control with the election of Aycock as governor. Connor was made chairman of the house Committee on Education and used his influence in opposing proposals to base the allocation of funds to white and black schools on the proportion of taxes paid by each race. He was also influential in effecting a compromise solution to the problem of railroad taxation and regulation, which had become a major issue in the state. It was neither education nor railroads, however, but impeachment that dominated the legislature of 1901, and on this controversy Connor was in a minority in his party and in the house.

The Fusionist legislature had established or altered positions to make places for Republican and Populist appointees, and the Democrats in turn in 1899 had made changes in an effort to oust these and other officeholders appointed during the Fusion period. The Republican and Populist judges who made up the majority of the Supreme Court of North Carolina declared a number of the changes unconstitutional, basing their decisions largely on Hoke v. Henderson, a precedent in North Carolina since 1833. Democrats in the house sought to impeach the judges for having ordered the payment of a salary for which there was no legislative appropriation. Connor agreed that the judges had been politically biased and that the legal principle on which they had acted was wrong, but he insisted that no one believed the judges personally dishonest and that a reprimand, rather than impeachment, was the wise remedy. He was able to secure only twelve votes in favor of his position; at the end of the session he left the legislature feeling that his public career was ended, but he was gratified when the senate did not vote to convict the judges.

In 1902, friends encouraged Connor to seek the Democratic nomination to the supreme court in spite of his unpopular stand on impeachment, and he was chosen by the party convention after a close contest. His election was therefore a matter of course, and he began service on the court in February 1903. In that session he delivered the majority opinion in Mial v. Ellington, overruling a decision of a lower court similar to that which had led to the impeachment trial, and also specifically overruling Hoke v. Henderson, thus establishing the ruling that a position created by the legislature could be altered or abolished by the legislature.

Connor's six years of service on the North Carolina Supreme Court were ended when he was nominated by President William H. Taft and confirmed in May 1909 by the Senate to serve as judge of the U.S. Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina. Taft's choice offended Republican leaders in the state but proved a popular one with most North Carolinians, doing much to alleviate the antagonism toward federal courts then prevalent. Connor left the North Carolina Supreme Court reluctantly, feeling that he could not refuse the unusual honor of Taft's nomination and responding to the urging of friends who thought his service would benefit the state. He held the position for the remainder of his life, even though in some ways he found the work of the federal court less congenial than his service in the state courts had been. He was troubled by the Department of Justice's insistence that the suspended sentence, which he thought a useful device in rehabilitating first offenders, was not permitted by federal law, and he was made particularly uncomfortable by trials relating to the enforcement of World War I draft laws. Among his last work as a federal judge was the settlement of cases growing out of the condemnation of land for the establishment of Fort Bragg. Although some of his decisions were appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, he had the unusual record of never having one reversed.

Connor was always conscious of his lack of formal education, which he felt rendered him unfit for service as a university trustee or professor, but in reality his devotion to his work, thorough study, and wide reading gave him a superior education that brought him respect as a scholar of law and of history. He was awarded the LL.D. degree by The University of North Carolina in 1908. He wrote a number of articles on lawyers and legal history and a biography of John Archibald Campbell published in 1902. He planned a biography of William Gaston, for which he undertook extensive investigation, but he completed only articles. He refused a professorship of law at The University of North Carolina in 1899 and again in 1922, when the trustees created the Thomas Ruffin Professorship of Law especially for him. He lectured in the Law School in the summer of 1923 and was in Chapel Hill for the same purpose in 1924 when he became ill. He died in Wilson and was buried there in Maplewood Cemetery.

Although Connor was a conservative in his political and economic views, opposed to sudden or drastic change, he was also open-minded and impersonal in considering new ideas and opposing viewpoints. He deplored intolerance in others and in 1923 devoted an entire grand jury charge to a discussion of the dangers inherent in such organizations as the Ku Klux Klan. He was so devoted to individual rights that he was far in advance of most of his contemporaries in his opposition to all corporal and capital punishment. He was known as a kindly and merciful judge but did not permit his sympathies to interfere with his judgment on the merits of a case. His personal dignity and calm were great assets in his profession.

Connor was a fine conversationalist with a great deal of humor, and his wide correspondence was marked by thoughtful consideration of many aspects of public affairs. His personal sweetness of disposition and his integrity of character made him one of the most loved and respected North Carolinians of his generation.

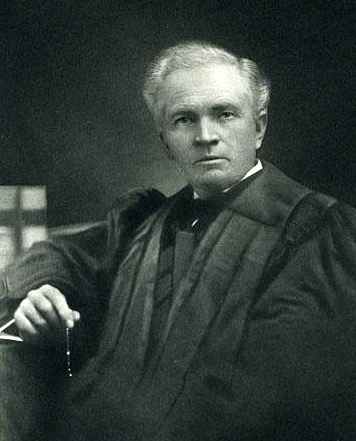

Portraits of Connor were presented to the three courts with which he was most closely associated: to the superior court of Wilson County went one painted by Irene Price; to the Supreme Court of North Carolina one by Mary Arnold Nash; and to the U.S. Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, Raleigh, one by Math Van Salk.