See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Americans by 1870 had grown accustomed to the notion that boundaries were made to be broken. In the previous half-century, the United States had become a continental nation, begun its ascent as the manufacturing titan of the globe, overcome the distances between its cities and its shores with 50,000 miles of railroad tracks, and emancipated the enslaved members of its society after a four-year civil war.

The Tar Heel State — Though North Carolina had been spared the worst ravages of the Civil War, few would have predicted in 1870 that the "Rip van Winkle State" would within fifty years become the most industrialized state in the South. Communities that were still barely hamlets five years after the war's end, such as Durham and Winston, and towns that served as commercial centers for the surrounding countryside, such as Greensboro and Charlotte, would in the decades ahead become centers of industry. But factories did not burgeon in cities alone. A rushing stream and a willing workforce opened the way for the creation of mill villages in the countryside wherever the capital could be collected. The value of goods manufactured in North Carolina was less than $10 million in 1870. It was almost $1 billion by 1920.

Though the folkways of country life persisted into the twentieth century, rural North Carolina was also transformed. Emancipation set the stage for the emergence of tenancy and sharecropping as the predominant labor system for the black farmers of the state. The coming of the railroads and the growth of commercial centers opened the way for thousands of white and black farmers to shift from subsistence agriculture to a concentration on the growth of cash crops. Greatest was the expansion of the tobacco crop of the state, which by the turn of the century surpassed 100 million pounds. By 1920 North Carolina tobacco filled many of the nation's cigarettes and pipes.

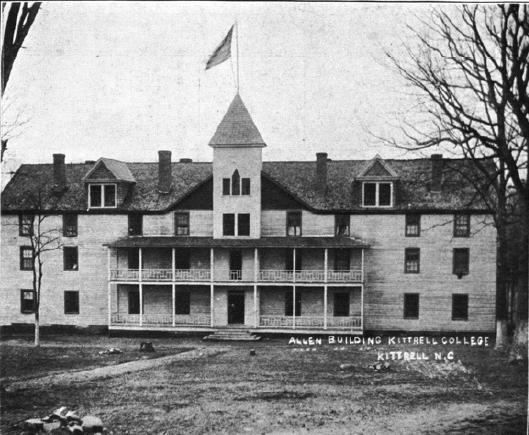

For black North Carolinians, the half-century after 1870 was a time of new freedom, new striving, and new setbacks. Enfranchised through federal law by the 1870s and politically active for three decades thereafter, they saw their voting and civil rights systematically revoked by state legislation after 1900. Widely employed as skilled artisans in North Carolina towns through the 1890s, they found their opportunities increasingly restricted and confined after the turn of the century. Throughout the uncertain years between legal emancipation and legal segregation and amidst the adversity intensified by disfranchisement and formal passage of Jim Crow laws, blacks built communities, churches, colleges, and business enterprises. In Edgecombe County, just across the Tar River from Tarboro, freed slaves started the community of Freedom Hill in 1865. After the community grew and was incorporated in 1885, its name was changed to Princeville to honor a resident, Turner Prince.North Carolina's Historically Black Colleges and Universities