See also:"Death to the Klan" March; Gastonia Strike; Ku Klux Klan; Lowry Band; Lynching; Red Shirts; Regulator Movement; Slave Rebellions; Wilmington Coup.

Group violence has occurred in many forms in North Carolina from the colonial era until the present day, perpetrated both by private citizens and public authorities and motivated by political differences, poverty, racism, labor unrest, and other forces. One of the earliest and best-known groups of North Carolinians who resorted to violence was the Regulators, who formally organized in the Piedmont in 1768. Frustrated by their failure to get redress from corrupt government officials, the Regulators turned to violence until they were eventually crushed by the forces of royal governor William Tryon at the Battle of Alamance in May 1768.

The American Revolution caused massive rifts in North Carolina society, leading to group violence apart from the formal military battlegrounds of the war. As the conflict dragged on, sporadic violence and resistance to government demands became more persistent and widespread. Small bands of private citizens, both Patriot and Loyalist, violently harassed their fellow citizens and occasionally experienced persecution at the hands of government agents. Chaos and violence reigned in the North Carolina Piedmont after the British army swept through the Carolinas in 1780-81. In the war's aftermath, with little government authority in place, marauding bands burned houses, robbed and sometimes murdered innocent victims, and waged pitched battles in towns and neighborhoods throughout the new state.

Although such conflicts, often rooted in economic hardship and ineffective local government, continued to occur during the early and mid-eighteenth century. The most prevalent and troubling form of group violence in North Carolina became that occurring between white citizens and Black people, both freed and enslaved. The inherent violence of the system of enslavement, which depended in large part on physical force and intimidation for its survival, often led to widespread fear of insurrections of enslaved people and consequential violent incidents. Following the Nat Turner Rebellion in Virginia in 1831, for example, various North Carolina militia and mobs suppressed supposed "copycat" insurrections in the state-at one location killing as many as 40 enslaved people who reputedly were organizing a rebellion against their enslavers.

The Civil War brought numerous instances of nonmilitary violence to the state as citizens again became motivated by vastly divergent political and social loyalties. Lawlessness reigned, particularly in the Mountain region, and violent conflicts often occurred. Confederate authorities were forced to send troops repeatedly into the same area in the 1860s "to quell, neutralize, and capture hundreds of deserters, draft dodgers, and militant Unionists." The Home Guard, organized to keep order, protect key military sites, and round up deserters, often used unnecessary and brutal violence to achieve these ends. Perhaps the most infamous conflict involving the Home Guard was in relation to the Lowry Band, a group of men led by a member of the Lumbee tribe, Henry Berry Lowry, that waged guerrilla war against authorities to protest forced labor and imprisonment in the Confederacy during the final year of the Civil War and for several years afterward. After members of the Home Guard had killed Lowry's father and brother, reputedly for theft and avoiding conscription, Lowry and his followers-Lumbee, Black, and white-murdered about 18 men before Lowry disappeared mysteriously in 1872.

The political and economic turmoil of the Reconstruction years, combined with the uneasy coexistence of white citizens and newly freed Black citizens in North Carolina society, led to years of sporadic violence and civil injustice incited by racial prejudice. Although the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and similar organizations appeared during Reconstruction in the eastern counties of Jones and Lenoir, white violent activity also saw more reprisals in the east, where the size of the population of Black North Carolinians and their participation in the local militia discouraged organized attacks by white agitators. Most of the night riding, physical assaults, and murders perpetrated by the KKK occurred in the Piedmont counties of Alamance, Caswell, Chatham, Orange, Cleveland, and Rutherford.

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, strained race relations had turned into full-blown, politically motivated violence (and in some cases terrorism) in many places throughout the state. At Reconstruction's end, North Carolina's Democrats-temporarily removed from power by the biracial Fusion and Republican Party coalition following the enfranchisement of Black men in 1868-began to employ violence as part of their efforts to regain control of the state and overturn Black political advances. Using a strategy fueled by white supremacy, disinformation, election fraud, and voter intimidation (see Red Shirt Campaigns), the Democrats regained prominence by the end of the century. Although lynching or mob actions perpetrated by white agitators against Black citizens were epidemic in the South in the 1890s and thereafter, these violent events never reached the level of intensity in North Carolina as they did in Deep South states such as Mississippi and Georgia. However, the Wilmington Coup of 1898 stands as an egregious exception. Remarks published by Alexander Manly, editor of the Daily Record, a Black newspaper in Wilmington, set off a wave of mob violence that ended with an estimated 250 Black deaths and immeasurable bad will between the state's white and Black communities. The coup was never reversed or amended by state or federal authorities and remains the only successful coup to occur in the United States. Ultimately, the Wilmington coup contributed to the disfranchisement of most Black people in North Carolina, helped install a one-party, Democratic-led system in the state, and solidified a legally segregated social order known as Jim Crow.

Violence involving labor disputes occurred in 1929 as textile workers, plagued by a decade of cost-cutting measures and technological change, confronted another round of wage cuts. Conflict between striking workers and the police in Gastonia received much national attention-partly because the strike was led by the communist-sponsored National Textile Workers Union and also because of the deaths of Gastonia police chief O. F. Aderholt and the strikers' balladeer, Ella Mae Wiggins. The carnage was worse at a subsequent strike in Marion, however, even though the walkout was initiated locally and led by the adamantly anticommunist United Textile Workers Union. The McDowell County sheriff and his deputies fired on picketers when they arrived at a mill for a second walkout, wounding 25 workers. Six of them eventually died. Sporadic violence between workers and local police and National Guardsmen also occurred in North Carolina during the General Textile Strike of 1934, although South Carolina suffered the worst casualties.

In the 1920s KKK activity increased in North Carolina and in many parts of the United States, as it did again during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Although the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement agencies did not consider the North Carolina KKK as violent as its Deep South counterparts, North Carolina Klansmen did engage in occasional bombings, dynamiting, and, at one point, a two-county spree of burnings and shootings into Black homes. One of the state's most famous KKK incidents took place on 18 Jan. 1958 near Maxton, where about 1,500 Lumbee activists disrupted a KKK rally days after Klansmen had placed burning crosses in the yards of an American Indian family in a Lumberton neighborhood and a white woman romantically involved with a Lumbee man. Shots were fired before KKK members fled the scene. Although there were no deaths and only one injury, the "Battle of Maxton" received widespread media attention.

The civil rights movement spawned several other instances of violence in North Carolina involving white and Black participants. In some communities, Black people took up arms to defend themselves and their rights while white people organized in violent opposition to their cause. In Monroe in the mid-1950s, members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by Robert Franklin Williams, armed themselves against persistent attacks on Black neighborhoods by local members of the KKK. When the home of NAACP member Albert E. Perry was attacked by a Klan motorcade, a Williams-led, armed squad drove it off. After taking part in further hostilities between Monroe's white and Black citizens as well as conflicts with leaders of the NAACP and the civil rights movement, Williams eventually fled to Cuba, where he began to broadcast a cultural and political program known as Radio Free Dixie.

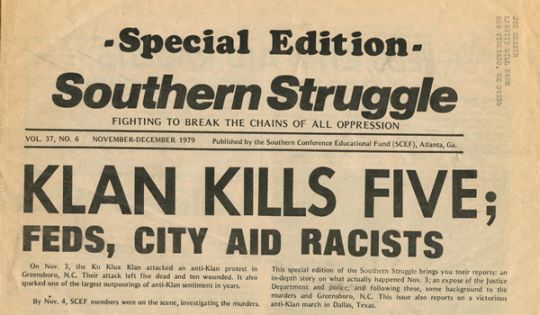

In 1970 the state endured another infamous racial murder when Henry D. Marrow Jr., a Black man, was attacked and killed by three white men who believed that Marrow had "flirted" with a local white woman. The acquittal of the three white perpetrators led to violent uprisings in Oxford and other places, as many Black activists rioted, some burning tobacco warehouses in the town. Another notorious act by the North Carolina KKK occurred in 1979, when Klansmen drove a nine-car caravan into a Black district in Greensboro and opened fire during an anti-Klan rally organized by members of the Communist Workers Party. Five people were killed and a number of others wounded. In federal court, none of the perpetrators was convicted of murder, and only a small number were found guilty of violating the marchers' civil rights. The event is still a painful memory to Greensboro citizens, who as late as the early 2000s formed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to explore the history of the incident and ways of bringing the community together in light of past racial conflict.