See also: Silver fusion; Fusion of Republicans and Populists; Red Shirts

The Wilmington Coup of 1898 was not an act of spontaneous violence. The events of November 10, 1898, were the result of a long-range campaign strategy by Democratic Party leaders to regain political control of Wilmington—at that time state’s most populous city—and North Carolina in the name of white supremacy. In 1894, a Populist and Republican coalition known as Fusionists had won control of the General Assembly and, in 1896, Daniel Russell, the state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction, was elected. Fusionists made sweeping changes to Wilmington’s charter and state government in favor of Black people and middle-class white people. Wilmington sustained a complex, wealthy, society for all races, with Black people holding elected office and working in professional and mid-range occupations vital to the economy.

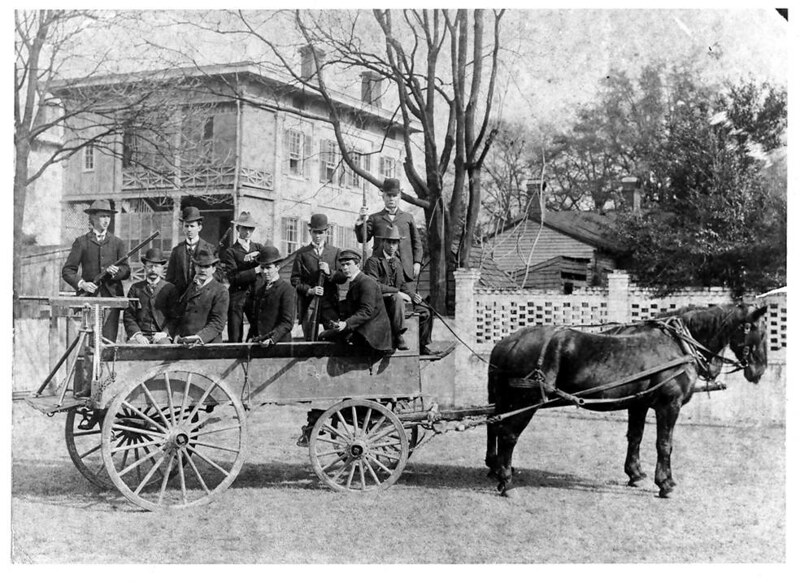

The Democratic Party’s 1898 campaign was led by Furnifold Simmons, who employed a three-prong strategy to win the election: men who could write, speak, and “ride.” Men who could write generated propaganda for newspapers. Men such as Alfred M. Waddell and future governor Charles B. Aycock gave fiery speeches to inflame white voters. Men who could ride, known as Red Shirts, intimidated Black people and forced white people to vote for Democratic Party candidates. Democrats from across the state took special interest in securing victory in Wilmington. A group of white businessmen, called the “Secret Nine,” planned to retake control of local government and developed a citywide plan of action.

An editorial by Alex Manly, editor of the Wilmington Record, the city’s Black newspaper became a touchstone of the campaign. Manly’s article challenged white concepts of interracial relationships, and it became a Democratic tool to further anger whites.

Because their campaign was so successful, Democrats won the election in Wilmington and across the state. The next day a group of Wilmington white supremacists passed a series of resolutions requiring Alex Manly to leave the city and close his paper, and calling for the resignations of the mayor and chief of police. A committee led by Waddell was selected to implement the resolutions, called the White Declaration of Independence. The committee presented its demands to a Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC)—prominent local Black citizens—and required compliance by the next morning, November 10, 1898.

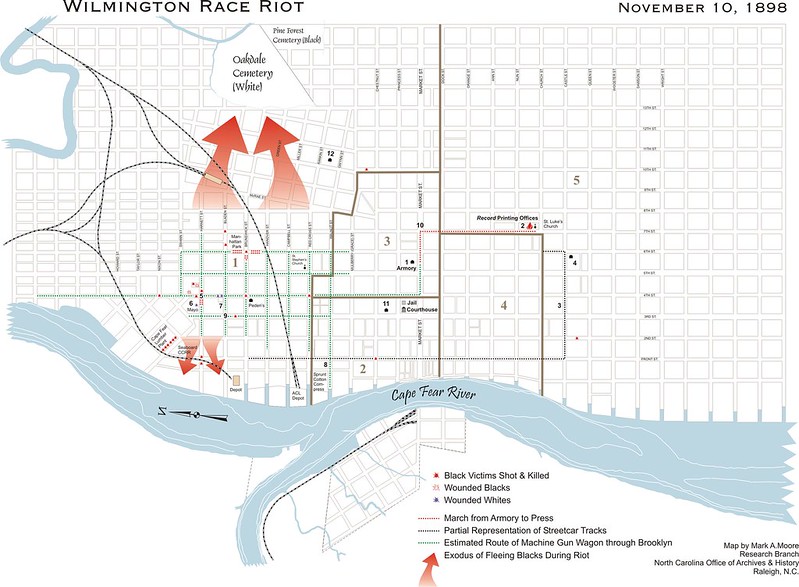

Waddell met a crowd of men at the Wilmington Light Infantry (WLI) Armory the morning of the tenth. Delayed response from the CCC and growing tensions enabled Waddell to organize as many as 2,000 white people to march on the Record printing office, where they broke in and burned the building. By 11:00 a.m., violence had broken out across town at an intersection where groups of Black and white people argued. Shots rang out and several Black men fell dead or wounded—each side claimed the first shot was fired by the other.

During the ensuing violence, Waddell and others worked to overthrow the municipal government; in essence, they staged a coup d’etat. By late afternoon, elected officials had been forced to resign and were replaced by men selected by leading Democrats. Waddell was elected mayor by the newly seated board of aldermen. Prominent Black citizens and white Republicans were banished from the city over the next days. Besides the primary target of Alex Manly, men selected for banishment fit into three categories: Black leaders who were open opponents to white supremacy, successful Black businesspeople, and white people who benefited politically from Black voting support. No official count of dead can be ascertained due to a lack of records – at least 14 and perhaps as many as 60 men were murdered.

State and federal leaders failed to react to the violence in Wilmington. No federal troops were sent because President William McKinley received no request for assistance from Governor Russell. The U.S. Attorney General’s Office investigated, but the files were closed in 1900 with no indictments. Black Americans nationwide rallied to the cause of Wilmington’s Black people and tried to pressure President McKinley into action.

Democrats solidified their control over city government through a new city charter in January 1899. Waddell and the board of aldermen were officially elected in March 1899 with no Republican resistance. The new legislature enacted the state’s first Jim Crow legislation regarding the separation of races in train passenger cars. A new suffrage amendment that disfranchised Black voters was added to the state constitution by voters in 1900. The Democratic legislature overturned most Fusionist policies and placed control over county governments in Raleigh. New election laws limited Republican power in the 1900 election. Democrats controlled local and statewide affairs for the next seventy years after victory in 1898.

Inside Wilmington, out-migration following the violence negatively affected the ability of Black Americans to recover. Black property owners were a minority of the overall Black population before the coup, and property owners were more likely to remain in the city. A collective Black narrative developed to recall the coup and place limits on relationships between Black people and white people for future generations. White narratives claimed that the violence was necessary to restore order, and their narrative was perpetuated by most historians who used the term "race riot" to refer to the coup.

Wilmington marked a new epoch in the history of violent race relations in the U.S. Several other high-profile massacres and coups followed Wilmington, most notably Atlanta (1906), Tulsa (1921), and Rosewood (1923). These examples of white supremacist violence against Black communities were also referred to using the misnomer "race riots." All four communities dealt with the aftermath of white supremacist violence differently; white people in Tulsa and Atlanta addressed the causes and some effects of violence and destruction soon after their events. White people in Wilmington provided compensation only for the loss of the building housing Manly’s press.