Silver Fusion was a national political movement of the 1890s in which North Carolina played a leading role. The movement originated with the desire for the free coinage of silver at a ratio of 16 ounces of silver to 1 ounce of gold, as provided for in the Coinage Act of 1837. The coinage of silver had been discontinued in 1873. This act of "demonetization" and the subsequent depression, by virtue of proximity, seemed related and led to widespread belief that ending silver coinage was a "Crime of '73."

The silver cause was given a significant boost in 1892-93 because of three developments: the election of Democrat Grover Cleveland, an advocate of the gold standard, as president; the adverse economic impact of the panic of 1893; and Cleveland's repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act as a solution to the economic crisis. A split in the Democratic Party occurred along sectional lines, with western and southern politicians on one side and easterners on the other. At the same time, the Populist, or People's, Party was drawn into the struggle on the side of silver. The greater part of the Republican Party continued to uphold the gold standard as the conservative course.

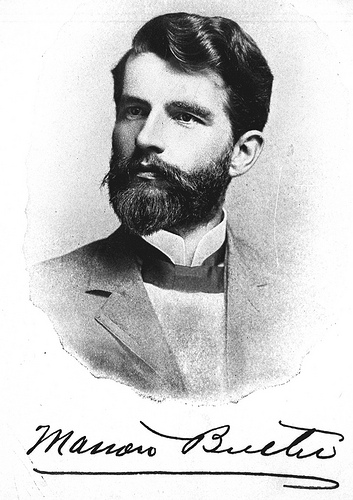

In 1894 the North Carolina Populist Party allied itself with the Republican Party in what is called the "Fusion" campaign. The two parties united over electoral issues, ignoring numerous differences in order to dislodge the Democrats and take control of the legislature. Two years later U.S. senator Marion Butler, leader of the North Carolina Populists, was chairman of the national People's Party. A fellow North Carolina Fusionist, Republican James J. Mott, was chairman of the National Silver Party.

Silver Democrats, led by former governor Thomas J. Jarvis and Raleigh News and Observer editor Josephus Daniels, were in the forefront of the state party by 1896. Daniels, as national committeeman, persuaded the North Carolina delegation to the Democratic National Convention to endorse William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska for president on 8 July 1896. After his nomination two days later, Bryan said of the North Carolina delegates: "Next to Nebraska, I owe them more than any other people."

The impetus for a fusion of reform forces around the silver issue was overwhelming. Mott had stated that North Carolina Fusion demonstrated "the practicability and safety of men of different parties cooperating to carry out a great measure." At his urging, the National Silver Party had nominated Bryan and Arthur Sewall, a Maine shipbuilding magnate. Butler, despite misgivings about Bryan's devotion to reform, went before the Populist Party convention to urge the Nebraskan's candidacy. The party concurred, but not before nominating Thomas Watson of Georgia in place of Sewall. After some haggling, the North Carolina parties agreed to a joint ticket of presidential electors consisting of six Democrats and five Populists.

Bryan carried North Carolina by a vote of 175,216 to 154,446 for Republican William McKinley, but the Republicans triumphed nationally. The Populist Party was especially weakened by the campaign, which had the effect of damaging its state-level alliance with the Republicans. Two years later, a successful "white supremacy campaign" swept the Democrats back into power. Fusion was at an end.

Free coinage as an emotional issue transcended its consequences. Silver fusion represented a pragmatic effort to build a political coalitions around currency reform, one of the great issues of the Gilded Age. North Carolina, both by action and example, played a historically significant role in the national fusion of silver forces.