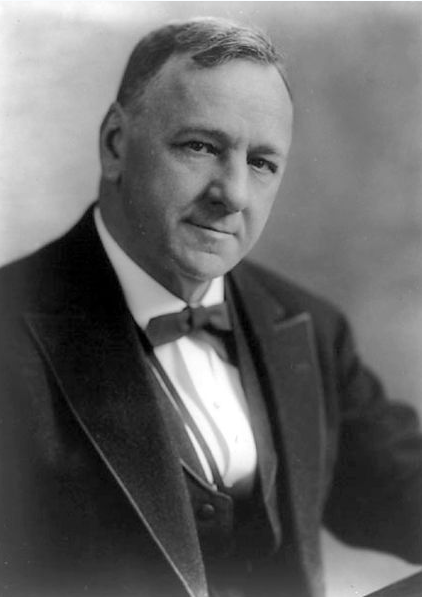

May 18, 1862 - January 15, 1948

A man is as old as his arteries and his interests. If he permits his economic, religious, or social arteries to harden, or loses interest in whatever concerns mankind . . . he will need only six feet of earth.

-- Josephus Daniels

The word "bystander" could never be applied to Josephus Daniels. Daniels emerged from war torn eastern North Carolina to establish a popular and influential newspaper and serve in high government offices. Daniels' career was marked by straightforward words and actions that sometimes offended opponents but left no doubt as to where Daniels stood. The influence of Josephus Daniels may still be seen today.

Daniels was born in Washington, North Carolina on May 18, 1862. The Civil War was in full fury, and the town of Washington changed hands several times. Josephus Daniels' father, also named Josephus, was a shipbuilder for the Confederacy and was killed before his son reached three years of age. Mary Daniels, Josephus' mother, started a small dressmaking business to support the family, but eventually moved the family to Wilson and became the postal official there.

The three Daniels brothers also worked to aid the family income. Josephus worked several odd jobs, which included picking cotton and clerking in a drug store. Eventually he found a job in a printing office, a position which set the stage for a lifelong career in newspaper publication.

At sixteen, Josephus and his brother Charles entered the newspaper field with the Cornucopia. Josephus also became an editor of Our Free Blade at about the same time. By the time he was eighteen, he had bought out his partners in the Advance, a paper serving Wilson, Nash, and Greene counties, and was the local editor. Daniels used his position at the helm of the Advance to address political issues ranging from trade to temperance.

In 1882, once again with his brother Charles, Josephus established another newspaper, the Free Press, in Kinston, North Carolina. The Free Press became a fiery pulpit from which Daniels campaigned for Grover Cleveland and the Democratic Party. Daniels' political activity and influence grew in coming years, but this political activity and his outspoken views in the Free Press cost his mother her job as postmistress in Wilson.

Daniels studied at the Wilson Collegiate Institute and in 1885 entered the Law School of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was admitted to the bar in 1885 but never actively practiced law. During this stage of his life, Daniels acquired the State Chronicle and the Farmer and Mechanic, both based in Raleigh. He merged the Farmer and Mechanic with the State Chronicle, publishing it initially as a weekly but later as a daily. The influence of the State Chronicle, combined with Daniels' past history of political activity, assisted him in his 1887 bid for and election to the office of Printer-to-the-State. He was reelected to this office in 1889, 1891 and 1893.

When the State Chronicle began losing money, Daniels sold the paper in 1892 and began the North Carolinian. When this paper also began to lose money, Daniels wrote to members of the Cleveland administration offering his services and was given positions in the United States Department of the Interior until 1895. While serving in Washington, Daniels purchased the News & Observer of Raleigh and merged it with the State Chronicle and the North Carolinian.

The News & Observer became extremely popular and prosperous. Daniels used the paper to advance the Democratic Party position on the issues of the day. The Democratic Party of the late 19th century was resentful of the Republican party and especially of the newly emancipated blacks. Daniels was also a proponent of the Jim Crow laws that were rampant at that time. The editorials of the News & Observer and their sensationalizing of crimes committed by blacks reinforced white supremacist views that neither party disputed. In this environment, Josephus Daniels and the News & Observer flourished, and the paper became the first newspaper in the world to have more subscribers than the population of the city in which it was based.

Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst offered Daniels one million dollars for the News & Observer. Daniels refused the offer. He continued to use the paper as an instrument for political influence battling the trusts, American expansion in the Philippines, Southern railroad companies who governed politics in the South, and others. Daniels' paper quickly earned the moniker "Nuisance and Disturber." One railroad company funded a competing paper in hopes of putting Daniels and the News & Observer out of business. Daniels' paper frequently sparked dislike, but the publisher is quoted as saying, "Dullness is the only crime for which an editor ought to be hung."

In spite of the anger of many readers of the News & Observer, Daniels was known as a man of courage and integrity. Once, held in contempt of court and fined $2,000, Daniels refused to pay the fine and spent three days in jail. He maintained an open door policy toward anyone who wished to speak with him. A sign on his office door read, "Office hours between 9 a.m. and 12:00 o'clock midnight. Can be seen at all other hours by calling Telephone 90."

As a member of the Democratic Executive Committee, Daniels and the News & Observer promoted Woodrow Wilson for the presidency in the election of 1912. Wilson was victorious and in return for Daniels' service and support, Wilson appointed him Secretary of the Navy. Daniels served in this office from 1913 through the war years to 1921. He was the last cabinet official to vote for a declaration of war against the Central Powers in 1917. Daniels appointed the young Franklin Delano Roosevelt as his Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Daniels supported creation of shipboard vocational schools for the training of enlisted men, attacked corrupt military contractors of armor plate, and increased the number of navy chaplains. He was also responsible for eliminating beer and wine onboard naval ships. According to legend, the term "Cup of Joe" began when sailors drank coffee in deference to Josephus' proscription of alcohol.

In 1932, Daniels was encouraged to seek the governorship of North Carolina, but refused. He endorsed and supported his old assistant, Franklin Roosevelt, for the presidency. After FDR's election, Daniels accepted the post of Ambassador to Mexico.

Upon Daniels' arrival, the Mexicans stoned the American Embassy. Although the American naval bombardment in April 1914 of the Mexican Naval Academy at Vera Cruz, preceding the American invasion of Mexico and the ousting of Mexican General Huerta, was blamed on Daniels, his speeches and policies while serving as ambassador to Mexico greatly improved relations between the two nations. He praised a proposed Mexican plan for universal popular education and, in a speech to U. S. consular officials, advised them to refrain from interfering too much in the affairs of other nations. Daniels also favored the Loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War, realizing that a collapse of the Spanish government would have dire affects on Mexico. When the health of Daniels' wife, Addie, failed, he resigned his post in Mexico to return to North Carolina in 1941.

Daniels had married Addie Worth Bagley on May 2, 1888, and the Daniels family grew to include four sons: Josephus, Worth Bagley, Jonathan Worth, and Frank A. III. After Addie Daniels died in 1943, the S.S. Addie Daniels was commissioned in her honor in 1944. Upon his return from Mexico, Daniels resumed the leadership of the News & Observer and continued his outspoken editorial style.

Daniels published several recollections of his years in public office. The Navy and the Nation, a collection of Daniels' war addresses as Secretary of the Navy, was published in 1919; Our Navy at War followed in 1922; the Life of Woodrow Wilson was published in 1924; and The Wilson Era in 1944.

Josephus Daniels died on January 15, 1948. During the course of his life, Daniels operated several newspapers, culminating with the News & Observer, which is still in operation today. He served in public office with a strong belief in improving conditions for labor and the working class. The story of Daniels' life closely mirrors that of North Carolina during the same time period. From the catastrophe of Civil War to national prominence, Daniels was a prime example of the strengths and weaknesses that marked the progress of his state. From the continuing presence of the News & Observer to the public middle school in Raleigh which bears his name, the influence of Josephus Daniels continues to be felt.