Tryon Palace is the restored and reconstructed mansion and government house originally built for North Carolina's royal governor William Tryon in 1770. Rising from the banks of the Trent River at the foot of George Street in New Bern, the building is an exact replica of the palace known in colonial America as "the finest government house in the colonies." Following the death of Governor Arthur Dobbs on 28 Mar. 1765, Tryon assumed the office of royal governor and promptly selected New Bern as the site of the capital of the colony. When the colonial Assembly convened in that city on 8 Nov. 1766, Tryon presented a request for an appropriation with which to construct a grand building in New Bern that would serve as the house of colonial government as well as the governor's residence. Less than a month later, the Assembly acceded to the governor's wishes by earmarking £5,000 for the purchase of land and the commencement of construction. The appropriated sum was borrowed from a fund that had been established for the construction of public schools. To replenish the depleted school fund, a poll tax and a levy on alcoholic beverages were imposed.

Tryon had laid the groundwork for the building, which would be known in his time as "Tryon's Palace," before he sailed from England for North Carolina to assume his duties as lieutenant governor in 1764. To assure that his future government house would be of the highest quality, he had persuaded John Hawks, a talented architect, to accompany him to the colony.

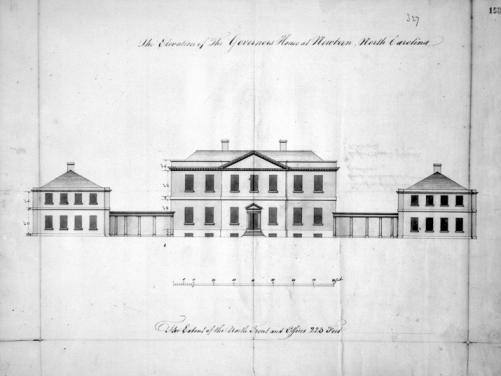

On 9 Jan. 1767 Hawks and Tryon executed a contract, which outlined the particulars for the construction of a massive brick structure with wings on either side. A year later, an additional £10,000 was appropriated to ensure completion of the project. When a strong hurricane struck New Bern in September 1769, two-thirds of the buildings in the city were lost, but the palace, then well under roof, survived the storm.

Tryon staged a grand gala to celebrate the official opening of the palace on 5 Dec. 1770. After years of moving from site to site, the colony's seat of government had been established permanently in an imposing structure. However, the extravagance of the palace and the taxes levied to pay for its construction further inflamed many backcountry residents, whose grievances were given voice by dissidents known as the Regulators. Consequently, Tryon spent the remainder of his tenure in North Carolina mired in controversy and conflict with the western dissidents. He left North Carolina to assume the governorship of New York in June 1771.

Josiah Martin, Tryon's successor as governor of North Carolina, took up residence in the palace on 11 Aug. 1771. He proceeded to fill the building with lavish furnishings at a time when the seeds of revolution were being sown in North Carolina and Britain's other American colonies. As the revolutionary fervor reached a fever pitch in North Carolina, Martin grew concerned for his safety in New Bern and fled the palace on 29 May 1776 in a coach bound for Cape Fear.

Abandoned by the royal governor, Tryon Palace fell into temporary disrepair. On 16 Jan. 1777, in the Council Chambers, Richard Caswell took the oath of office as the first governor of the state of North Carolina. Caswell promptly obtained legislative authority to restore the buildings and grounds of the first capitol of the state. Most of Martin's furniture was confiscated by the new government and purchased at auction for use in the palace.

Abner Nash succeeded Caswell as governor on 17 Apr. 1780, but he was forced to abandon the palace soon thereafter as Lord Charles Cornwallis's army threatened to enter North Carolina. To aid in the war effort, much of the eight tons of lead that had been used in the construction of the palace was removed and melted into musket balls. After the departure of Nash, the legislature met in the palace two more times, considering on each occasion bills that addressed the repair of the palace and the appointment of caretakers for it. These caretakers were encouraged to rent out rooms in the structure to help defray the expenses of its operation and maintenance. Some consideration was given to selling the palace in an attempt to balance the state budget.

In the wake of the successful conclusion of the Revolutionary War, Tryon Palace continued to deteriorate. Vandals and thieves stripped the building of its valuables, and vagrants took shelter and brawled in the very rooms where the affairs of state had been conducted. Richard Dobbs Spaight, the previous owner of several lots on which the palace had been erected, took the oath of office as governor in the building on 14 Dec. 1792. Two years later, as the new State Capitol in Raleigh neared completion, the state legislature met for the final time at the palace, thus ending the reign of the building as the state's seat of government.

On the evening of 27 Feb. 1798, when a torch accidentally ignited some dry hay, the central portion of the palace burst into flames. By morning, Tryon Palace was mostly a smoldering ruin. Only the west wing survived the conflagration, and over the next 150 years, it was used alternately as a warehouse, a dwelling, a stable and carriage house, a school, and a chapel. In 1925 some interest in rebuilding Tryon Palace on its original site was generated by the Daughters of the American Revolution, historians, and local citizens, but the Great Depression intervened. By 1931 the west wing had been converted into an apartment building.

Renewed interest in a possible restoration inspired Governor Gregg Cherry to create the 25-member Tryon Palace Commission in 1945. The original palace site, which by that time was covered with 54 deteriorating houses fit for demolition, was acquired by the commission with a legislative appropriation of $227,000. Maude Moore Latham, a New Bern native who had played in the palace ruins as a child, served as commission chairperson and also provided substantial financial resources for the project. She established a living trust of $250,000, acquired $125,000 worth of antique furnishings, and bequeathed an additional $1.12 million for the restoration that she did not live to see completed.

In 1951 William G. Perry, of the Boston firm that had restored Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, was appointed restoration architect. He benefited from two original copies of the palace drawings by Hawks. One set was found in the New-York Historical Society Library, and the other was located at the British Public Record Office in London.

In addition to the extensive historical research that went into the project, archaeological evidence proved beneficial once excavation began. Five feet under George Street, workmen located the original foundations. As the excavations progressed, interior designers were aided by the discovery of pieces of marble, brass, molding, and glass. Completed at a cost of $3.5 million, the restored Tryon Palace was opened to the public on 8 Apr. 1959. It quickly became one of the most heavily visited historic sites in the state.