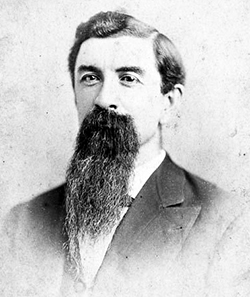

24 Apr. 1837–11 June 1892

Leonidas LaFayette Polk, agrarian leader, was born in Anson County, the only child of Andrew Polk and his second wife, Serena Autry. The father was a middle-class farmer who practiced diversified agriculture—cotton, corn, oats, cattle, hogs—and at the time of his death enslaved thirty-two people. The mother died two years after her husband, when Leonidas was fifteen. In sharing the estate with three half brothers, he received 353 acres and seven enslaved people. He attended neighborhood schools, read widely, and benefited from the guidance of several sympathetic, responsible adults. Certain that he wanted to be a "gentleman farmer," the young man enrolled at Davidson College in 1855 and completed with distinction one year as a special student. He then returned to Anson, married, received 300 more acres of land on approaching his majority, and developed a keen interest in politics.

As an ardent Union Whig he was elected to the state House of Commons in 1860. After President Abraham Lincoln's call for troops against the South the following spring, Polk declared himself "for resistance to the bitter end." He led a joint house-senate committee in the creation of a state militia; commissioned a colonel, he performed the delicate task of applying compulsory service legislation in his home county. In May 1862 he transferred to the Twenty-sixth North Carolina Regiment (as a private, then sergeant-major) commanded by Colonel Zebulon B. Vance. After Vance's election as governor, however, Polk joined the Forty-third Regiment (as a second lieutenant), in which he served until returned to the legislature in 1864. After the war he also won election to the constitutional convention that restored North Carolina to the Union. For the next eight years he devoted his energies chiefly to restoring his war-ravaged property and caring for his growing family. At length he opened a country store, started the weekly Ansonian, and, as the new Carolina Central Railroad approached his farm, sold lots, attracted settlers, and incorporated the town of Polkton.

The appearance of his paper's first number in 1874 signaled Polk's return to public affairs. He advocated Zeb Vance for governor two years hence for conservatism over radicalism, and he championed diversification—"raise your own bread and meat"—while condemning the one-crop—"all cotton"—system. It was his conviction that the Grange, of which he was a leader, could exemplify necessary education and cooperation. Together, and with Governor Vance's backing, they initiated action resulting in a state Department of Agriculture in 1877 with Polk as commissioner. Utilizing a tax on commercial fertilizers, the agency quickly became a prototype for five other southern states. Following Vance's election to the U.S. Senate, however, the department's conservative governing board so crippled the agency that Polk resigned in 1880. Shortly afterwards he joined the daily Raleigh News.

As a roving reporter he campaigned for development of the state's resources and revealed himself as a strongly partisan Democrat. In 1881 he efficiently managed the state fair; in 1883 he exerted strong influence towards the reorganization of the state Board of Agriculture. But three business ventures he launched in the early eighties failed. Polk then returned to journalism and agricultural leadership as he began the weekly Progressive Farmer on 10 Feb. 1886. He strove to make the paper of practical value to farm families, encouraged farmers to organize clubs to advance their interests, and insisted that the annual federal land-grant fund under the Morrill Act be transferred from The University of North Carolina to a separate institution that would teach "practical" subjects. Each goal was attained. When the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts was established at Raleigh in 1887, Polk's prime role became apparent. Leaders of his denomination then called upon him to push through a long-dormant project to create a Baptist school for girls—ultimately Meredith College in Raleigh.

The farmers' club movement initiated by Polk made North Carolina receptive to the Farmers' Alliance in 1887. Since the Grange had declined and farmer grievances were mounting, this predominantly southern organization had great appeal. Facilitated by Polk, the Alliance rapidly gained thousands of members and impressive strength over the next four years. First came the North Carolina Farmers' Association, formed in connection with the struggle for the agricultural college. Several months later, in Atlanta, the Inter-State Farmers' Association, a group of southern farm leaders, elected Polk president by acclamation and repeated their action at Raleigh in 1888 and at Montgomery in 1889. Both organizations were absorbed by the great Farmers' Alliance. Following a year as first vice-president and another as chairman of the executive committee, Polk in 1889 became president of the two-million-member Alliance and was reelected in 1890 and 1891. Farm distress was acute during these years. He and other officers, with headquarters in Washington, D.C., planned, organized, corresponded, published, lobbied, and exhorted. But their opposition—the industrial and financial interests of the Northeast and Midwest—seemed unyielding.

Polk participated vigorously in the political campaigns of the early nineties. Endowed with personal warmth, great energy, and oratorical skill, he traveled by train to almost every state in behalf of the farmers' cause. He elaborated the Alliance's panacea for agriculture's ills, the "sub-treasury plan"; he fervently called for an end to North-South sectionalism. The focal point in the West was Kansas, where the new People's party (Populists) threatened to combine with the minority Democrats to overthrow the Republicans. Polk made two speaking trips to Kansas in 1890 and still another the next year. As in the West, the political power of the Farmers' Alliance in the South became formidable. The African American issue, however, dictated that the Alliance endeavor to control the Democratic majority rather than form a third party, which might result in a Republican victory. When the Kansas Republicans lost in the elections of 1890, and hundreds of Alliance-backed candidates won in both the West and the South, the farmers' revolt gained national attention. "We are here to stay," said Polk. "This great reform movement will not cease until it has impressed itself indelibly in the nation's history."

As leader of the Alliance, largest of the many organizations campaigning for the farmer and the laborer, Polk himself drew much notice. At the annual meetings of the Alliance at Ocala, Fla., in 1890 and at Indianapolis in 1891, third-party speculation was rampant and his name was often mentioned in that connection. By the latter year he was convinced that neither major party would legislate for farm relief. Indeed, Congress had defeated a vital "free silver" bill and refused even to discuss the sub-treasury plan. Polk therefore saw his plain duty: to do all in his power to promote the success of the now national People's party. Already he had been bitterly attacked by both the Kansas Republicans and the North Carolina "Bourbon Democrats." But "Alliance Democrats" in his home state scored heavily in 1890, enacted the following year the most progressive legislation since antebellum times, and in 1892 held the balance of political power.

Thousands of Tar Heel farmers enlisted with Polk in the People's party in 1892. Yet more thousands who admired him—more conservative, fearful of a third party, aware of their strength—stayed with the Democratic party. Marion Butler, young president of the State Alliance, proposed fusion of Democrats and Populists in state politics. Polk naturally opposed the plan: "I cannot give such a policy my endorsement. . . . I am an out and out People's Party man." Both rejoiced, nonetheless, when the Democratic state convention nominated for governor an outstanding allianceman, Elias Carr, over the incumbent Bourbon, Thomas M. Holt.

Nationally the first landmark of 1892 was St. Louis, where 1,200 delegates from many reform organizations assembled on 22 February to agree on a platform and arrange for a subsequent People's party convention. Polk served as permanent chairman and conferred at length with other Populist leaders. The body then made the site Omaha and the date 4 July; 1,776 delegates were authorized to nominate the third-party ticket. By spring, sentiment began to crystallize on the nomination of Polk for president. His leadership of the Alliance, acceptability to diverse reform groups, and crusade against sectionalism combined to sway many minds. He was willing and zealous. So strongly did his Progressive Farmer on 24 May favor the Populists, however, that the State Alliance executive committee objected; as official organ the paper was required to be nonpartisan. Whereupon Polk, possibly misunderstanding, submitted his paper's resignation. This trying decision, the realization that the Bourbon Democrats would support the Alliance Democrats against the Populists in North Carolina, overwork and overstrain, and the aggravation of a physical ailment of four years finally overcame him. He died in the Garfield Memorial Hospital, Washington, and was buried the next day in Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh.

L. L. Polk was a great-great-grandson of William Polk of Carlisle, Pa., common ancestor of the North Carolina Polks, and a second cousin to Leonidas Polk, churchman, educator, and Confederate officer. He married Sarah Pamela Gaddy of Anson County on 23 Sept. 1857. They had six daughters and a son who died in infancy. The daughters who bore children were Juanita Polk Denmark and Carrie Polk Browder.