10 Apr. 1806–14 June 1864

Leonidas Polk, Episcopal bishop and Confederate corps commander, was born in Raleigh. His father, William Polk, was a soldier in the American Revolution (at Brandywine, Germantown, and Camden), maintained a close relationship with Andrew Jackson, and contributed to the advancement of education in North Carolina. His mother, Sarah Hawkins, was the sister of North Carolina Governor William Hawkins. Many members of the Polk family settled in Tennessee and by 1840 held a "commanding position."

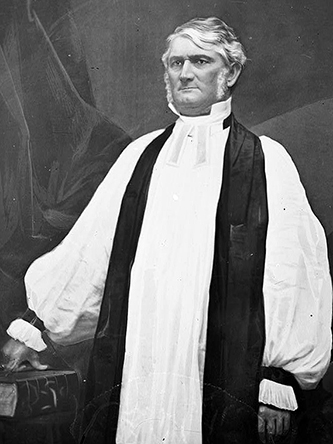

Leonidas Polk attended The University of North Carolina for two years (1821–23) before entering the U.S. Military Academy. There he roomed with Albert Sidney Johnston, developed a close friendship with Jefferson Davis, and achieved a remarkable academic record. During his final year, Dr. Charles P. McIlvaine, a newly assigned chaplain, converted Polk to the Episcopal church. After only six months service, Polk resigned his commission and entered the Virginia Theological Seminary. He was ordained deacon in April 1830 and priest in May 1831. In 1830 he married Frances Ann Devereux, the daughter of John Devereux of Raleigh. They became the parents of eight children: Alexander Hamilton, Frances Devereux, Katherine, Sarah, Susan R., Elizabeth D., William Mecklenburg, and Lucia. After a short assignment as assistant rector in Richmond, he resigned because of poor health and traveled and studied. In 1834 he assumed his duties at St. Peter's Parish in Columbia, Tenn., surrounded by his relations.

In 1838 Polk was consecrated missionary bishop of the Southwest. This extensive area of scattered settlements comprised the states of Arkansas, Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and a section of the Indian Territory. During the first six months of 1839, he familiarized himself with the region, having "travelled 5,000 miles, preached 44 sermons, baptized 14, confirmed 41, consecrated one church and laid the cornerstone of another." "It is in extent about equal to all of France." His journeys on horseback across most of the lower South gave him a knowledge of the area rivaled by few of the Confederate high command.

Polk settled in Louisiana in 1841, having been consecrated bishop of Louisiana in that year. For twelve years he attempted unsuccessfully to manage a vast sugar plantation at Bayou la Fourche while performing his ecclesiastical duties. Polk was also a prolific enslaver; Polk's Leighton plantation in Bayou la Fourche was worked by over 400 people that he enslaved. He conducted ceremonies for the people he enslaved, often marrying them with ceremony in the "big house" and establishing a Sunday school on the place. In 1849, a cholera outbreak killed one hundred of the people Polk enslaved, and, in 1854, Polk lost the plantation because of heavy debts.

In the five years preceding the Civil War, Polk's chief concern was the establishment of the University of the South. To supply the Episcopal clergy for the Middle South and to educate properly the lay leadership, he labored to raise funds adequate to erect "a university which would rival the establishment at Harvard or Yale." Through the assistance of Bishop Stephen Elliott and many others, about ten thousand acres were purchased at Sewanee, Tenn., and on October 19, 1860 Polk laid the cornerstone for the university.

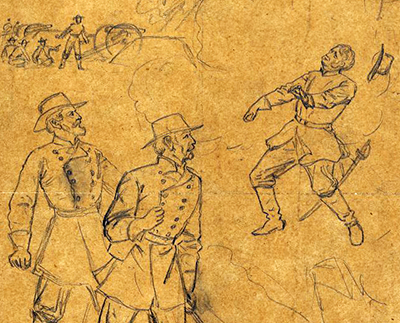

In the spring of 1861, President Jefferson Davis and many other Southerners urged him to enter the Confederate army. Despite his lack of military experience, Polk accepted the appointment as major general, considering it "a call of Providence." Polk was passionately committed to the Confederacy, and he felt that it was his duty to enlist in times when "constitutional liberty seems to have fled." Polk's presence was an emotional asset to the Confederacy throughout the war and offset his limitations as a commander.

In the summer and fall of 1861, he accepted responsibility for the defense of the Mississippi River, the importance of which he continually stressed. Despite successes with the occupation of Columbus in September and the defeat of Ulysses S. Grant's force at Belmont in November, Polk's efforts failed, largely because of Albert Sidney Johnston's insistence on the consolidation of the western forces of the Confederacy. Polk resigned in November 1861, when Johnston withdrew five thousand men from Columbus, but was placated by Davis.

At Shiloh, Polk earned a reputation for courage and displayed an ineptitude for logistics. During the invasion of Kentucky in 1862, he upheld his combat record but worked at cross purposes with his commander, Braxton Bragg, thereby helping to undermine the campaign. Commissioned lieutenant general in October, Polk succeeded in fielding a corps noted for high morale and dogged fighting. At Murfreesboro in December 1862 his corps sustained frightful losses and accomplished little with repeated frontal attacks. The spring of 1863 found Polk continually quarreling with Bragg and urging Davis to have Bragg replaced. The Bragg-Polk controversy raged following Chickamauga, and Davis settled the irreconcilable conflict by sending Polk to Mississippi. Polk's actions at Chickamauga were open to criticism but hardly justified Bragg's demand for a court-martial.

Following the disaster at Chattanooga in November 1863, Polk rejoined the army now commanded by his friend Joseph Johnston. Under Johnston, Polk proved himself to be an able, competent corps commander. His corps maneuvered well and fought well. The end came at Pine Mountain in June 1864. Polk and his staff were observing the enemy lines when Union artillerymen spotted them. Polk ordered his staff off the hill but remained for a last look. A shell from a ten pounder hit him, killing him instantly.

The Army of Tennessee mourned Polk's loss. He had inspired the army for three years. His fellow corps commander, William J. Hardee, wept when he learned of Polk's death. The loss of this experienced corps commander hurt the chances of the Army of Tennessee in the heavy fighting around Atlanta. One young Confederate felt that "a fair investigation of his record in the army as a general and in the church as a priest makes it evident that there was a very eloquent, earnest bishop, spoiled to make an ordinary general." Another soldier, a Tennessean who fought under Polk for three years, stated, "'Bishop Polk' was ever a favorite with the army, and when any position was to be held, and it was known that 'Bishop Polk' was there, we knew and felt that 'all was well.'"

Leonidas Polk was buried first in Augusta, Ga., and later in Christ Church Cathedral, New Orleans. Three portraits of him may be found in the University of the South.