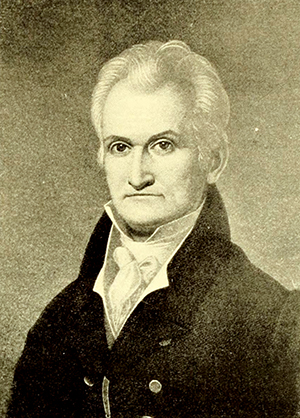

9 July 1758–14 Jan. 1834

William Polk, lieutenant colonel of the Revolution, banker, and political leader, was born in Mecklenburg County. He was a descendant of Scots-Irish emigrants who went to the Eastern Shore of Maryland in the early eighteenth century. His paternal grandparents were William and Margaret Polk. Thomas Polk, his father, moved to Sugar Creek, near the Catawba River, about 1753 and soon married Susanna Spratt, whose parents had recently moved to the area from Pennsylvania. Thomas and Susanna had eight children, of whom William was the oldest. Thomas represented Mecklenburg in the General Assembly and saw service in the Revolution.

William Polk was attending Queen's College in Charlotte when the rebellion against England began, and he was a witness of the Mecklenburg Convention in May 1775. Though only seventeen, he joined a South Carolina regiment as a second lieutenant and fought there against loyalists; he was wounded at the Battle of Canebrake on December 22, 1775. After eleven months of recuperation he was commissioned a major in the Continental service, and in March 1777 he joined a regiment at Halifax. His regiment marched from there to join George Washington's forces in New Jersey. In September he fought in the Battle of Brandywine and in October his jawbone was shattered at Germantown. During the winter he was hospitalized at Valley Forge before being sent home to do recruiting during most of 1778 and 1779. In 1780, he was again on duty in South Carolina, where he participated in the August Camden campaign and the retreat back into his home area and on to Guildford Court House by the following March. By May 1781 he was back in South Carolina, now a lieutenant colonel under Thomas Sumter. He was present at Eutaw Springs on September 8th when his brother was killed.

After the war Polk was a leader in the formation of the Society of the Cincinnati in North Carolina. In 1783 the General Assembly appointed him surveyor general of the district around present-day Nashville, Tennessee, and Polk moved there to take up his duties. Twice he was elected to represent Davidson County in the North Carolina House of Commons. While in the future Tennessee, he made many contacts and acquired large tracts of land under his own name.

Returning to Mecklenburg in 1786, he represented his Mecklenburg County in the House of Commons in 1787, 1790, and 1791. In the latter year he was Federalist candidate for speaker of the Assembly and was regarded as one of the leading Federalists in the state. In October 1789 he married Griselda Gilchrist, a granddaughter of Robert Jones, Jr., colonial attorney general under Governors Arthur Dobbs and William Tryon. During this period the young couple had two sons: Thomas Gilchrist (b. 1791) and William Julius (b. 1793). The colonel was a trustee of The University of North Carolina from 1790 until his death and served as president of the trustees from 1802 to 1805. In March 1791 he was appointed federal collector of internal revenue for his native state, a job he held until 1808. Girselda died in 1799 and shortly afterwards Polk moved to Raleigh. Around that time, Polk was elected grand master of the state Masonic order, serving from December 1799 to December 1802.

On New Year's Day 1801 Polk married Sarah Hawkins, daughter of Colonel Philemon Hawkins, Jr., of Warren. They had eleven children; one son, Leonidas, became an Episcopal bishop and a lieutenant general in the Confederate army. Their daughter Mary married George E. Badger and their other daughter Susan married Kenneth Rayner. Both in-laws were later leading Whigs.

During the Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe administrations, Polk was a leader of the Federalist opposition in North Carolina. Federalists in the Assembly nominated him as their candidate for governor in 1802, but he was defeated by John Baptist Ashe, 103 to 49. He became first president of the State Bank in 1811 and held that post for eight years. When the War of 1812 began, the state's delegation in Congress offered Polk command of a North Carolina regiment with the rank of brigadier general but he declined, being opposed to the war with England as were most Federalists. Only after the British burned Washington did he give up his opposition to the conflict. The wartime governor of the state was William Hawkins, Polk's brother-in-law.

Near the end of the war, in 1814, Assembly Republicans could not agree on a successor to Governor Hawkins and Federalists tried to capitalize on this division and elect Polk. After the Assembly voted, Federalists claimed that Polk received more votes than either Republican candidate but the Republicans quickly combined their count and announced William Miller to be the victor. Polk's supporters believed that the results were fraudulent but were forced to accept the decision.

While in Raleigh, Polk was busy with speaking engagements and public meetings during his later years. He was active in the American Colonization Society. He was a strong advocate of constitutional reform and internal improvements, and he headed in 1826 a company to develop navigation on the Neuse River. Feeling that John Quincy Adams was responsible for the death of federalism, he worked hard to keep Adams out of the White House. He was a leader of the Jackson-Calhoun movement in 1824 and 1828. In 1827 there was another brief attempt to have the Assembly elect him governor. By 1832 Polk developed reservations about Jackson's dictatorial ways and tried to subvert Jackson's choice for his running mate by supporting the Barbour movement against Martin Van Buren.

William Polk was also an enslaver. The number of people he enslaved varied throughout his lifetime. According to the 1790 Census of Mecklenburg County, William Polk was the enumerated enslaver of 21 people. In 1800 census of Wake County, he was the enslaver of 23 people. By 1820, 31 people were enslaved by Polk. In a May 22, 1823 settlement, Polk was also recorded to have been paid $600 for the labor of some enslaved people he had hired out. The enslaved laborers worked to build the Old West residence hall on UNC Chapel Hill's campus, of which Polk was a trustee. The names of the people he hired out were Jourdan, Jim, Stephen, Charles, and Joe.

William Polk died at home at age seventy-five and was buried in the Morgan Street Cemetery. Both North Carolina and Tennessee have counties named for him. During World War I, a tank camp outside Raleigh also bore his name.