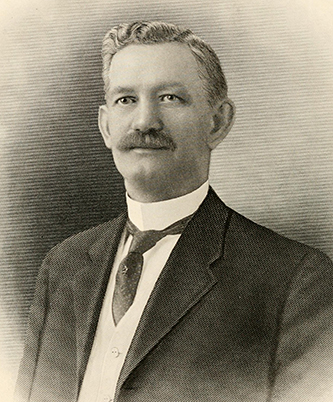

26 Oct. 1859–3 Oct. 1933

Robert Newton Page, businessman and congressman, was born in Wake County at what was then commonly known as Page's, or Page's Station, but which is today the city of Cary. His father, Allison Francis Page, owned extensive timberlands in the area and engaged in lumbering. Although he owned a number of slaves in the 1850s, the elder Page disliked slavery and, like many of the yeoman class in his district, only reluctantly supported the secession movement of 1860–61. Robert's mother, Catherine Frances Raboteau Page, a native of Fayetteville, was well educated by the standards of the day, having attended private female academies in Raleigh and Louisburg.

In 1880 Allison Francis Page and his family, which by this time included five sons and three daughters, moved to Aberdeen, Moore County, where eventually they developed substantial business holdings. Indeed, the Page family pioneered in the economic development of the Sandhills section of the state.

Robert was the second born of the five Page brothers, all of whom achieved success in one capacity or another. Walter Hines (1855–1918), the eldest brother, became a well-known journalist and author but is best remembered as the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain during World War I. Henry (1862–1935) served in the state legislature from 1913 to 1918 and as wartime state food administrator. Junius (1865–1938) became a prominent Aberdeen businessman whose career was largely devoted to the supervision of family-controlled railroad, lumbering, and banking enterprises. Frank (1875–1934), the youngest brother, was the able chairman of the North Carolina Highway Commission in the 1920s and subsequently executive vice-president of the Wachovia Bank and Trust Company.

Robert Page was educated at Cary Academy, which his father helped to found, and at the Bingham Military Academy in Mebane. In his early business career he was associated with several of the family enterprises, being at one time or another general manager of the Page Lumber Company and an official of the Aberdeen and Asheboro Railroad Company. In the late 1890s he moved to the town of Biscoe in Montgomery County and in 1901–3 represented Montgomery in the lower house of the General Assembly.

In 1902, Page, a Democrat, was elected to Congress from the Seventh Congressional District. He served a total of seven terms in Congress (1903–17), where his most important committee assignment was as a member of the powerful Appropriations Committee.

As a congressman, Page supported President Woodrow Wilson's domestic program. He voted, for example, for the Underwood Tariff (1913), the Federal Reserve Act (1913), and the Clayton Anti-Trust Act (1914). But he was among those Democratic congressmen from rural constituencies in the South and West who, led principally by Congressman Claude Kitchin of North Carolina, opposed the president's preparedness program and criticized his neutrality policies. In 1916 Page, among others, sought unsuccessfully to reduce the expenditures provided for in the administration-supported naval appropriations bill. In the same year he complained in a letter to his constituents that Wilson's policy of allowing private bankers to extend loans to belligerent powers had "destroyed the semblance even of neutrality . . . and will probably lead us into the war." Page again found himself at odds with the president when the McLemore Resolution, warning American citizens to refrain from traveling on armed belligerent ships, was before the House. Although he personally favored such a congressional warning, Page, motivated largely by a reluctance to break party ranks and to embarrass Wilson, finally capitulated to the president's wishes by voting to table the resolution.

Page's view on Wilson's preparedness and neutrality policies contrasted sharply with those of his brother Walter Hines Page, the staunchly Anglophile ambassador to Great Britain. More significantly, however, Robert's failure to support the president wholeheartedly during critical times alienated many of the voters of the Seventh Congressional District. Declaring that he could not follow the president's leadership, as seemingly demanded by his constituents, without violating his "self-respect and intellectual integrity," Page announced in March 1916 that he would not seek reelection.

He retired from Congress in 1917 and returned to Biscoe. In May of that year, a month after America's entry into World War I, Governor Thomas W. Bickett appointed him a member of the North Carolina Council of Defense, in which capacity he served throughout the war. Page's last attempt at public office came in 1920, when he challenged Cameron Morrison and O. Max Gardner in the Democratic gubernatorial primary. His platform, which endorsed a highway development program, increased expenditures for education, and expanded public health services, bespoke progressive principles. At the same time, however, he campaigned as the business candidate, stressing economy and efficiency in state government. His advocacy of "Industrial Democracy," or corporate profit-sharing with employees, alienated many businessmen who otherwise might have voted for him. Lacking adequate press support and an effective statewide political organization—and less colorful than Morrison and less affable than Gardner—Page waged a losing battle almost from the start of the campaign. He was eliminated in the first primary, in which he carried only eleven of the state's one hundred counties, and in the runoff Morrison defeated Gardner.

Soon afterwards Page moved to Southern Pines and shortly thereafter to Aberdeen, where from 1927 until his death he was president of the Page Trust Company.

Robert Page was a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and for thirty-five years served as chairman of the board of trustees of the Methodist Orphanage in Raleigh. He was also a trustee of the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts and, in 1931–32, president of the North Carolina Banker's Association. On 20 June 1888 he married Flora Shaw of Manly, and the couple had four children: Robert N., Jr., Thaddeus, Richard, and Kate. Page was buried in Old Bethesda Cemetery near Aberdeen.