22 Mar. 1882–6 Feb. 1947

See also: Oliver Maxwell Gardner, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History, Fay Gardner

Oliver Maxwell (O. Max) Gardner, attorney and governor, was born in Shelby. His father, Dr. Oliver Perry Gardner, had two children by his first wife and ten by his second, Margaret Young. Max was the youngest of the twelve children. The father, a farmer, served as a Whig and Anti-Secessionist in the state legislature, fought in the Civil War, and then, having lost his property as a result of the war, made his livelihood in the hard life of a country medical doctor. Max's mother died in 1892 and his father seven years later, and he was brought up by his older sisters.

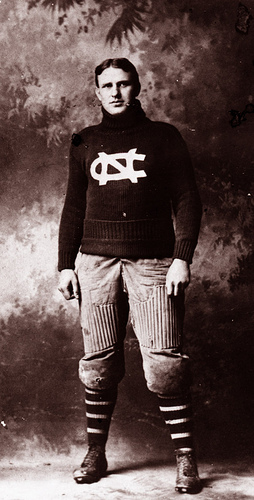

After attending local schools in Cleveland County, he entered North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts and received the bachelor of science degree in 1903. While in college he excelled in debating and athletics; he was captain of the football team and president of his class. Two years after his graduation he taught chemistry—his major in college—there while reading law in Raleigh with Richard J. Battle. Afterward he entered the law school of The University of North Carolina where he again played football. In 1931, the university gave him an honorary LL.D. Gardner passed the bar examinations in 1906, coached football that fall at Hampden-Sydney College, and then began to practice law in Shelby. On 6 Nov. 1907, he married Fay Webb, the daughter of James L. Webb, judge of the local superior court and the brother of Congressman E. Yates Webb. In the meantime, Gardner's sister, Bess, had married Clyde R. Hoey, local newspaper owner and lawyer, later governor and U.S. senator. These marriages created what came to be known as the "Shelby dynasty," sometimes called the Gardner machine, which succeeded the F. M. Simmons organization as the leading center of political power in the state. The Gardners had four children: Margaret Love (1908), James Webb (1910), Ralph Webb (1912), and O. Max, Jr. (1922).

Gardner became active in local politics in 1907. In the following year he supported the victorious campaign for prohibition, which he described as hopefully "the last great battle against the drink evil in our state." He was elected to the North Carolina Senate in 1910 and again in 1915, when he supported a statewide primary law; a year later he was elected lieutenant governor. In spite of his youth, Gardner became a leading candidate for governor in 1920. The Democratic primary was a three-cornered race between Gardner, Robert N. Page, and Cameron Morrison. Morrison had the advantage of being a longtime political friend of Senator F. M. Simmons. Gardner, however, hoped to rally the young men to his cause in an attempt, as he put it, to "smash the old boys." He did succeed in forcing

Morrison into a runoff, but Morrison won easily in the second primary. Nevertheless, Gardner emerged from the campaign with an enhanced reputation, although he decided not to challenge Simmons's friend, Angus W. McLean, for governor in 1924, perhaps in accord with the tradition that governors should alternate between the eastern and western portions of the state. In any case, there seems to have been a tacit agreement with Simmons that Simmons would not oppose Gardner in 1928. In the meantime, while keeping his political irons in the fire, Gardner devoted himself to his family, teaching the men's Bible class at the First Baptist Church, practicing law, buying land, raising cotton, experimenting with rural electrification, and building up what was to become a multimillion dollar rayon mill, Cleveland Cloth Mills, at Shelby.

In 1928, although Gardner was nominated for governor without opposition, the party was divided over the nomination of Alfred E. Smith for president. Gardner disliked Smith's stand on prohibition, but, concluding that Smith as president could not repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, supported him with consummate caution in order not to jeopardize the state ticket. Gardner defeated his Republican opponent, but Smith, whom Simmons opposed, did not carry the state. In 1930, Josiah Bailey, with Gardner's support, defeated the seventy-six-year-old Simmons in the Democratic primary for U.S. senator. Now Gardner was clearly the leading political power in the state.

He began his term as governor hoping to promote "reorganization, retrenchment and consolidation." Despite the unforeseen complications of the depression, he carried forward a constructive program. He succeeded in pushing through an Australian ballot bill and a workman's compensation act. He achieved greater centralization in administration by making more officers appointive rather than elective, creating a permanent tax commission, shuffling and reorganizing state agencies, and consolidating The University of North Carolina, North Carolina State College, and the North Carolina College for Women. He gained state responsibility for maintaining roads and the public school system. Faced from the beginning with a perhaps unprecedented financial crisis, he cut state salaries, raised the gasoline tax, and, after a bitter fight, helped persuade the legislature to increase corporation taxes and impose a modest ad valorem tax on property. In an equally bitter fight, he succeeded in defeating the imposition of a sales tax. Throughout this critical period, his personal reputation was an important factor in maintaining the state's credit and in securing short-term loans to pay state employees.

As governor, he was compelled to deal with serious labor unrest. In 1929, it hit the textile towns of Gastonia and Marion. In Gastonia Communist labor organizers were involved. In both cases, violence erupted, people were killed, and local justice was found wanting. Gardner's actions during these crises, however, won national praise. He called out the National Guard and attempted to see that justice was done in the courts. He expressed a lack of sympathy for communism, but insisted that Communists had the right of protection under the law. He attacked doctrinaire employers, criticized long hours in textile plants, and stated that "we cannot build a prosperous citizenship on low wages."

In the presidential campaign of 1932, Gardner supported Franklin D. Roosevelt, with whom he had become acquainted as a fellow governor, and during the 1930s North Carolina had considerable influence on the national government. In 1933, Gardner opened a law firm in Washington and was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court. A specialist in tax matters, he soon became an effective lobbyist for numerous organizations such as the Cotton Textile Institute, the Rayon Producers Group, and Coca-Cola. Generally he supported the New Deal and approved its legislation regarding hours, wages, working conditions, and collective bargaining. Roosevelt frequently called upon him for advice and for help in writing speeches, and Gardner occasionally carried out semiofficial chores such as negotiating the government's air mail contract. However, he opposed the plan for reconstituting the Supreme Court and was so disturbed by Roosevelt's attempts to defeat senators Walter George, Ellison D. Smith, and Millard Tydings in the primaries of 1938 that he quietly helped organize Senator George's campaign to retain his senatorial seat.

During the war years, Gardner's principal official contribution was as chairman of a twelve-member advisory board to the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion. In this capacity he occasionally came into conflict with the office's director, James Byrnes. Under Gardner's leadership, the advisory board insisted upon the authority of the War Man Power Commission, rather than Selective Service, to supervise assigning draft-age men to civilian employment, urged Congress to work out an "equitable tax program," and in the summer of 1945 supported the continuation of the Office of Price Administration. In February 1946, President Harry S Truman appointed Gardner undersecretary of the Treasury. His post on the advisory board had been unsalaried, and he had accepted it with the understanding that he might continue his law practice. Now he resigned from the law firm and renounced any claim to "fees for legal services rendered" before assuming his responsibilities as undersecretary. He continued as chairman of the advisory board until the summer of 1947. Gardner was passed over when Vinson left the Treasury to become chief justice of the Supreme Court, and inexperienced John Snyder was appointed secretary. But Gardner remained loyally at his post. He worked hard to reorganize the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the Bureau of Customs, and developed a joint accounting system that was to coordinate the Treasury, the Budget Bureau, and the General Accounting Office.

On 3 Dec. 1946, Truman appointed Gardner ambassador to the Court of Saint James, perhaps because of his part in negotiating a British loan and his attempts to improve trade relationships with that country. Gardner's health had not been good for years. He had given up the thought of a senatorial campaign against Robert R. Reynolds in 1943, largely because of low blood pressure, gall bladder trouble, and chest pains. On 19 Oct. 1946 he suffered a heart attack, but rested only over the weekend. At 3:00 A.M. on 6 Feb. 1947, the morning that the Gardners were to sail for England, he was awakened by extreme chest pains, and at 8:25 A.M. he died of a coronary thrombosis. The funeral service was at the First Baptist Church, Shelby, and the burial in Sunset Cemetery.

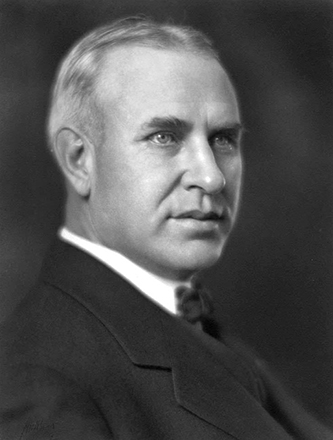

Gardner was a handsome man, six feet two inches tall with broad shoulders and ruddy complexion; a fascinating storyteller; and fond of good food and drink. Although tactful and pragmatic, he was ready to stand on principle and to defend his position brilliantly and loudly. He established himself as North Carolina's most influential politician by an ability to make and retain friends, by shrewd appointments and an effective centralization program while governor, and by his strength and probity of character. He was a successful lawyer and businessman (he sold his principal mill in Shelby for more than $3 million in 1946); yet he fought for improved labor conditions, scientific agriculture, the elimination of tenant farming, and more equitable race relations. While in Washington, he was a popular and influential personality moving easily in the company of businessmen and bureaucrats, newspapermen, congressmen, and presidents. Withal he had the virtue of modesty, which made him uncomfortable, for example, when his favorite philanthropy, Boiling Springs Junior College, was renamed Gardner-Webb College.