See also: Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission; Anti-Saloon League; Blind Tiger, Temperance Movement; Turlington Act.

Prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors in North Carolina was in effect statewide between 1909 and 1935. As early as 1852 a petition seeking prohibition was presented to the General Assembly, but no legislative action was taken. Antiliquor forces did gain enough influence in the Democratic Party in 1881 to win the legislature's approval of a popular referendum on the measure, but it was overwhelmingly defeated by a vote of 166,325 to 48,370.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many municipalities were allowed to regulate the sale of alcohol through dispensaries controlled by town commissioners. In 1903, at the urging of a newly organized Anti-Saloon League, the Democratic-controlled legislature passed the Watts Act, prohibiting the manufacture and sale of spirituous liquors except in incorporated towns. According to historians Hugh T. Lefler and Albert Ray Newsome, the law was designed "to get rid of the county distilleries," which Democratic Party leader Furnifold M. Simmons called "Republican recruiting stations." In 1905 the Ward Law extended Prohibition to incorporated towns of fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, meaning that 68 of the 98 counties in the state had Prohibition.

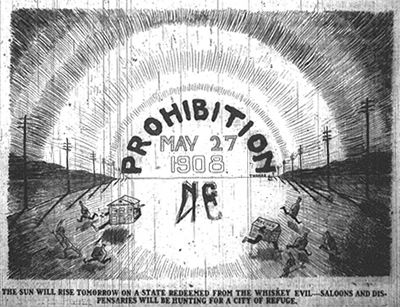

The Anti-Saloon League and Governor Robert B. Glenn finally convinced the General Assembly to authorize a statewide referendum on Prohibition, which was scheduled for 26 May 1908. The measure passed by a vote of 113,612 to 69,416, with 21 counties voting against it. Statewide Prohibition became effective in January 1909. In 1913 Congress passed a law making it illegal to transport liquor from wet states into North Carolina and other dry states; six years later, the Eighteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution established Prohibition as federal law.

Prohibition was slowly phased out in North Carolina after national Prohibition was repealed in 1933. "Light" wine and beer sales were allowed soon afterward, and a county-option liquor law in 1937 established the Alcoholic Beverage Control system.