See also: Resorts.

North Carolina's mountains, beaches, scenic attractions, and historic sites annually draw millions of visitors, and even greater numbers of people visit the state's largest cities. Professional sports franchises and events, convention centers catering to businesses and organizations, and unique shopping opportunities have made metropolitan areas such as Charlotte, Raleigh and Durham, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem the state's most popular and profitable tourist destinations.

Before the Civil War, various Coastal, Piedmont, and Mountain communities were noted for their healthful climate, mineral springs, hotels and resorts, and grand scenery. Leisure travelers from inside and outside the state made extensive use of these areas, but such economic activity remained a seasonal, local concern. A true statewide travel and tourism industry did not emerge until the 1880s as developments in transportation created new possibilities for tourism on a larger scale. Tourists from southern and northeastern states began to enjoy rail access to a variety of North Carolina resorts from the mountains to the Atlantic beaches. This opened the state to new groups of potential visitors, and developers soon set about constructing large resorts to accommodate and entertain them. Travel during this period was still limited to the wealthy elite, and new facilities such as Asheville's Battery Park Hotel, Raleigh's Yarborough House, and New Bern's Hotel Albert reflected the refined tastes of visitors. By the First World War, cities offering unique natural or recreational attractions, such as Asheville, Pinehurst, and Wilmington, attracted thousands of tourists each year.

By the 1920s, the Department of Conservation and Development began to promote North Carolina as a tourist destination in official state publications. In 1933 Governor O. Max Gardner, recognizing the emerging importance of tourism to the state's economy, ordered the creation of a Bureau of State Advertising, a new agency devoted to tourism promotion. Gardner's successors all appointed some type of citizens' committee to advise state officials on tourism-related matters and backed a variety of promotional and construction projects to better attract potential visitors. By the 1950s, tourism was a leading component of the state's economy, accounting for more than $100 million annually.

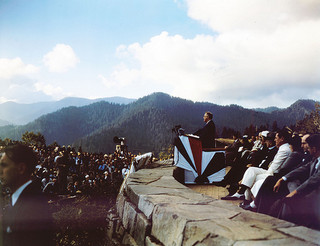

These developments occurred at a time of important growth in the state's tourism infrastructure. Much of this growth came as a result of federal New Deal programs aimed at combating the Great Depression. During the 1930s, the state saw the establishment of important attractions such as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Blue Ridge Parkway, and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, as well as several national forests. These large public attractions emerged as cornerstones of tourism development within their respective regions.

After World War II, the wealthy elite no longer dominated North Carolina tourism. Motor lodges replaced luxury resorts as the lodging of choice among vacationers. This democratization of travel led to the development of a ski industry, amusement parks such as Carowinds (near Charlotte) and Ghost Town in the Sky (in Maggie Valley), and numerous other local attractions. The state's many Atlantic beaches continued to attract North Carolinians as well as travelers from other eastern states. In the 1990s the Cherokee Indian Reservation added bingo and video gambling to its list of attractions in an effort to draw larger numbers of visitors. During the 1950s, cultural tourism emerged, catering to a traveling public interested in history, architecture, and traditional crafts. Public and private historical attractions such as the Bentonville Battlefield, the Thomas Wolfe House, the Biltmore House, and Tryon Palace continued to draw thousands of visitors each year. Natural attractions remained popular despite increased commercialization of the travel and tourism industry. By the 1980s, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park emerged as the most visited national park in America. National and state preserves across the state continue to draw large numbers of visitors who enjoy fishing, hiking, boating, or simply taking in the natural landscape.

Expansion of the travel and tourism industry initially benefited owners of small motels, restaurants, gasoline stations, and similar businesses. Communities had a vested interest in promoting tourism and extending hospitality to visitors because income generated by tourism stayed in the local community. By the 1960s and 1970s, large national motel chains, franchised eateries, and other businesses slowly eroded the market of many smaller, locally owned businesses. Organizations that own many of North Carolina's large commercial attractions are often headquartered outside the state. While generating revenue and providing profit for many, tourism workers do not share in the industry's prosperity. Tourism workers, often women and minorities, are among the lowest-paid laborers in the state.

By 2006 the Division of Tourism, Film, and Sports Development had become North Carolina's central tourism agency, overseeing a $12.6 billion-a-year industry created by approximately 49 million annual visitors to the state.