See also: Equal Rights League.

Freedmen's conventions in 1865 and 1866 voiced the aspirations of Black North Carolinians, both those previously classified as free and formerly enslaved. The Civil War had been over only five months when more than 100 men, almost all from Piedmont and eastern counties, gathered at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Raleigh and opened the "Convention of the Freedmen of North Carolina," the first such statewide assembly of Black people. Many delegates were newcomers to North Carolina; most of the others were counted among the state's antebellum free Black residents, who referred to themselves as "colored men."

The timing of the convention was significant. Under a Reconstruction plan announced by President Andrew Johnson -- himself a native of Raleigh -- white voters had chosen delegates to a constitutional convention that would be held in the State Capitol on 2 Oct. 1865 to repeal the ordinance of secession, abolish slavery, and prepare for the state's return to the Union. Barred from participation in the election of delegates, the freedmen upstaged the official convention by meeting three days earlier, on 29 September. Emphasizing their seriousness, the Black delegates agreed to open each session with devotionals and expel any participant found intoxicated during the sessions.

The largest delegation to the convention was from Craven County (including six members from the Black-controlled community of James City). James Walker Hood, a missionary from Connecticut, was elected president of the convention. In his acceptance speech, Hood said: "We and the white people have to live here together. Some people talk of emigration for the black race, some of expatriation, and some of colonization. I regard this as all nonsense. We have been living together for a hundred years and more, and we have got to live together still; and the best way is to harmonize our feelings as much as possible, and to treat all men respectfully." He called for three constitutional rights for Black citizens: admission of testimony in court, representation in the jury box, and "the right to carry [a] ballot to the ballot box."

Delegates Abraham H. Galloway of Craven County, Isham Sweat of Cumberland County, and James H. Harris of Wake County "made speeches advocating equal rights, and a moderate conservative course in demanding them." Among the messages received from outside the hall, famed New York editor Horace Greeley, who had been married in Warrenton, urged the delegates to be hopeful, patient, peaceful, and diligent, to respect themselves, and to stay in North Carolina, "a noble state, with her resources mainly undeveloped."

All of the speeches were reportedly moderate and respectful; in a formal communication to be delivered to the (white) constitutional convention and the General Assembly, suffrage and judicial reform were not specifically mentioned. Before adjourning on 3 October, the convention resolved itself into the North Carolina State Equal Rights League and adopted a constitution intended to secure "by political and moral means, as far as may be, the repeal of all laws and parts of laws, State and National, that make distinctions on account of color."

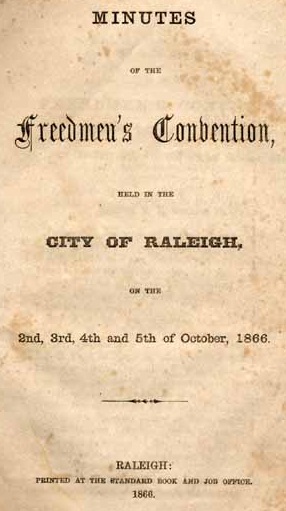

At the urging of James H. Harris, president of the State Equal Rights League, a second freedmen's convention was held in the same church sanctuary on 2 Oct. 1866. Again delegates numbered more than 100, but this time several western counties were also represented. Over some objections, Governor Jonathan Worth and former governor William W. Holden were invited to address the participants. Worth, who spoke on morality, education, and religion, was greeted by delegate J. R. Good as a personal friend and one who had voted for Good's emancipation in a previous session of the legislature. The convention then sang a hymn, after which the governor retired "amidst loud and hearty cheers." Two days later Holden lectured on the importance of goodwill between the races. The freedmen needed first to "get homes" and second "to educate their children."

That all was not harmonious in the state was recorded in conflicting reports to the 1866 convention. E. M. Bell of Lenoir County complained that his people had been "outraged" and the Freedmen's Bureau had done little on their behalf. In Bertie County, Charles Harrel charged, "colored men were cheated out of their labor, children were taken and bound without the consent or consultation of their parents," grievances echoed by Charles Carter of Sampson County. Louis Heagie of Forsyth declared that most Black residents in his county were in "an abject state of poverty." Conversely, a Guilford County delegate "informed the Convention that the greatest feeling of love and unity existed between both races in his county," and Edmund Bird of Alamance County maintained that "prejudice existing against the negro is only entertained by the lower and ignorant class of whites, whilst the intelligent and better classes are disposed to help the negro."

H. J. Brown, a delegate from Hertford County, appeared before a racially mixed audience to give an evening lecture-described as "one that would have done credit to the most learned person"-on "Phrenology and Ethnology." Arguing that "no two races on the face of the globe were so much alike as the Caucasian and the Negro", Brown maintained that "the same imitative, moral and intellectual faculties" were found in the brains of both races. Black inferiority, if true, "is owing to the state of slavery under which they have been kept, not allowing the faculties of the mind to be developed; therefore it is the white man's shame." Brown was not as charitable to American Indians, who "will not accept nor can be made to appreciate arts, science, literature and religion . . . showing the negro race superior to the American Indian, and in every respect equal to Caucasian or Anglo Saxon." Brown later donated the $22 he collected for his lecture to help pay for the convention.

The historic freedmen's conventions of 1865 and 1866 were the first meetings where Black North Carolinians from across the state openly and collectively expressed their goals. The names of delegates such as James H. Harris, John Hyman, and James E. O'Hara would become familiar in the remaining decades of the century. The convention journals reveal the care with which the freedmen sought to air their complaints without antagonizing whites, whose influence was essential for a realization of their hopes. The conventions were overtly partisan (national Republican policies were repeatedly applauded), but they occurred before developments in 1868 drove a violent political wedge between Black and white North Carolinians. The published proceedings thus reflect a period of relative goodwill between the races.