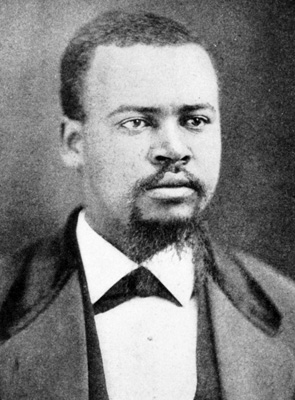

23 July 1840–14 Sept. 1891

John Adams Hyman, politician, state senator, and congressman, was born enslaved near Warrenton, Warren County. Sold and sent to Alabama, he returned to Warren County in 1865 a free man. With the rise of African American participation in North Carolina politics, Hyman became a delegate to the second Freedman's Convention held in Raleigh during 1866. The following year, he was a delegate to the first Republican state convention and attended the Republican state executive committee meeting. With North Carolina a part of Military District Number Two, under E. R. S. Canby, he also was chosen a "Register" for Warren County to assist in the registration of voters in 1867. In 1868, he became a delegate to the North Carolina Constitutional Convention.

Also in 1868 Hyman, together with three other African Americans, was elected to the North Carolina Senate. Representing the Twentieth Senatorial District (Warren County) from 1868 to 1874, he supported civil rights for African Americans during both his terms. However, his efforts were clouded by his involvement in frauds and payoffs of significant proportions: irregular activities as a member of a committee to locate a site for a penitentiary, accepting money from lobbyists during the Milton S. Littlefield-George W. Swepson railroad bond scandal, and demanding money from a congressional candidate in return for his support. Aside from these episodes, Hyman's participation in legislative matters was minimal.

Hyman was a strong political campaigner. With Warren County a part of the gerrymandered Second Congressional District, also known as the "Black Second," he decided to run for Congress. Although defeated in 1872, he was elected in 1874, thus becoming the first Black person to represent North Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives and the only Republican to represent North Carolina in the Forty-fourth Congress (1875–77). Hyman supported all legislation to secure and protect the rights and privileges of African Americans, and he strongly supported suffrage rights. His votes on issues arising from the Civil War and Reconstruction reflected his Republican sentiments. For example, he opposed the appointment of former Confederate officials to federal posts, as well as the removal of disabilities imposed on southern leaders by the Fourteenth Amendment. His stand on the main issues confronting the Congress also demonstrated his party affiliation. He supported Rutherford B. Hayes over Samuel J. Tilden in the disputed presidential election of 1877, which was decided by Congress; he favored a third term for Ulysses S. Grant, whom he avidly supported; and he opposed the resumption of specie payments.

After serving one term in the House, Hyman failed to obtain his party's nomination in 1876. This was due in part to his limited participation in Congress, an unwillingness of white Republicans to support him, a factional split among the African Americans in the Black Second, and the old accusations of fraud and corruption that still haunted him from his days in the state senate.

In private life, Hyman worked as a farmer and ran a combination liquor-grocery store in Warrenton. In 1872 he began to mortgage his real estate, and by 1878 he had disposed of all his land. Undoubtedly, campaign expenses contributed to his financial reverses, but his extravagances in the nation's capital were his undoing. He was constantly in debt. Writing to Judge Thomas Settle in March 1877, Hyman said that he was in "desparate need." An appointment by President Hayes to the post of collector of internal revenues at New Bern was withdrawn when town residents rallied on behalf of the collector already in office. In 1879, Hyman was accused of using funds from the treasury of the Black Methodist Church in Warrenton. Shortly afterwards, he left Warrenton for Washington, D.C., to become an assistant mail clerk. He remained an employee of the Post Office Department until 1889, when he obtained a minor position in the Agriculture Department.

Hyman spent his last years in Washington, D.C., where he died of a stroke. He was survived by his widow, two sons, and two daughters.