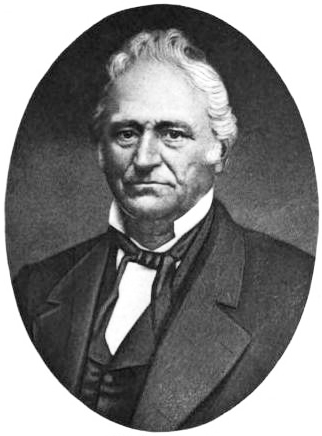

30 Oct. 1798–3 Oct. 1868

William Rainey Holt, physician, public servant, and planter-enslaver, was born in Alamance County, the oldest son of Michael and Rachel Rainey Holt, and the grandson of Captain Michael and Jean Lockhart Holt. He had two brothers (Alfred Augustus and Edwin Michael) and three sisters (Jane Lockhart, Polly, and Nancy). His mother was the daughter of the Reverend Benjamin and Nancy Rainey, the former a prominent minister of the Christian church. His father was a prosperous planter who served in the North Carolina House of Commons in 1804 and in the state senate in 1819 and 1821–22, during which terms he advocated internal improvements in the state.

Holt was graduated from The University of North Carolina in 1817 and obtained a medical degree from the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Always desirous of keeping abreast with the newest scientific and medical discoveries, he attended clinics yearly in Philadelphia even after he was firmly established in his profession. Holt opened a practice in Lexington, where he soon became known not only as a good physician but also as a community builder. Skilled and dedicated, he sought to improve sanitary conditions and to combat many superstitions prevalent in that day.

When Holt moved to Lexington, Davidson County had not yet been created. After the formation act was passed by the legislature in 1822, he became one of the foremost leaders in its implementation. In 1823 he was commissioned a justice of the county Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions; when a dispute arose over the location of the county seat, Holt was sent by the court to The University of North Carolina to enlist the support of his good friend, President Joseph Caldwell. After Lexington was named the county seat by a new act of the legislature, Holt purchased lots at the county auction and was appointed to various committees concerned with building a courthouse, a poor house, and even a gallows.

The young physician was one of the first members of St. Peters Episcopal Church in the 1820s and served as a vestryman for many years. He was a trustee of the Lexington Academy in 1825 and of the Lexington Female Academy in 1858. During a term in the state senate in 1838–39, he strongly supported passage of the Education Act and was chairman of the committee on internal improvements. At home he worked for a tax for common schools in the county; in 1843, after the tax was finally voted, he became a member of the first Davidson County Board of Superintendents of Common Schools. He also supported the establishment of the first cotton mill in Lexington and pioneering efforts in the cotton industry elsewhere by his brother, Edwin Michael Holt, and others. When the Railroad Act was passed in 1849, he played an important role in the location and building of a railroad through the county; two stations—Holtsburg and Linwood, the name of his farm—were named in his honor.

Soon after settling in Lexington, Holt began buying farmland in the Jersey Settlement near the Yadkin River. Deeply interested in agriculture, he spent much of his time at his farm, trying out new methods about which he had read or heard. He read the latest agricultural publications and maintained a close friendship with scientific agriculturists like the editor Edmund Ruffin, Professor Ebenezer Emmons, and Judge Thomas Ruffin, whom he succeeded as president of the state Agricultural Society. Holt effectively used such advanced practices as deep plowing, proper drainage, and turning under clover and peas to enrich the soil; commercial fertilizers; and the latest farm machinery. The yields per acre at Linwood were considered phenomenal. Not only his neighbors but also agriculturists from all over the state, and even from Richmond and Baltimore, went there to learn of his experiences.

Although cotton was the chief cash crop, no doubt sold to his brother's cotton mills, the plantation was almost self-sufficient with a variety of other products. Newspapermen who rode on the train through this productive farmland became poetic in their descriptions of the green fields and the herds of improved sheep and cattle. Holt purchased outside the state a purebred Short Horn bull and brought him to Linwood, with the registration papers completed a short time afterwards. This was the first registered animal of any breed of cattle in North Carolina. "When his sons and daughters went to college, each week a large wagon of supplies consisting of beef, mutton, pork, vegetables as well as water-ground flour and meal, was sent from the plantation, which was a great help to the schools as well as helping pay for the education of the boys and girls." The people that Holt enslaved were recorded as being well-fed, clothed, and housed. The people enslaved by Holt that he deemed the most "skilled" were also appointed as overseers to supervise other enslaved peoples' work.

Because of his agricultural achievements, his public service, and his medical knowledge and skill, Holt was well known across the state. When newspapermen wrote about Lexington, they often closed with the statement, "Dr. Holt lives here." Distinguished judges and attorneys attending court in Lexington would be entertained in Holt's home, considered by all as an ideal residence.

In 1822 Holt built a house on South Main Street where he took his bride, Mary Gizeal Allen, a descendant of William Allen, who had married Mary Parke, of the Parke-Custis family of Virginia. They had five children: Elizabeth Allen, who married Dr. Dillon Lindsay; Elvira Jane, who married Joseph Erwin; Louise, who died young: Mary Gizeal, who married Colonel Ellis, a brother of Governor John Willis Ellis; and John Allen.

In 1834, two years after the death of his first wife, Holt married her cousin, Louisa Allen Hogan, daughter of Colonel William and Elizabeth Allen Hogan. William Hogan was a son of Colonel John Hogan, a Revolutionary War officer whose wife Mary was a daughter of General Thomas Lloyd. Holt bought land adjoining his first house, which he removed, and built The Homestead, an imposing residence of distinctive architectural features (which still stands). Here were born their nine children: Louisa, Julia, Franklin, James, William Michael, and Eugene Randolph, all of whom died unmarried (William Michael, an officer in the Confederate Army, died in Richmond in 1862, and Eugene Randolph died a prisoner of war on Johnson's Island in 1865); Claudia E., who married D. C. Pearson; Frances, who married Charles A. Hunt of Lexington; and Amelia, who married William Edwin Holt, son of Edwin Michael Holt.

Holt was a Democrat and a Secessionist. Firmly believing in the Confederate cause, he was deeply disturbed by the South's defeat. Soon after the war ended, former Governor John Motley Morehead died at Rock Bridge Alum Springs, Va., where Holt had accompanied him in the vain hope of curing his illness.

Although he grieved over the outcome of the war and the loss of his friend and his children, Holt worked resolutely to supervise his plantation under new conditions. His exposure to all kinds of weather caused more suffering from rheumatism and wore down his physical resistance. He was buried in the Lexington City Cemetery.