16 May 1799–1 Oct. 1863

Ebenezer Emmons, geologist, educator, and physician, was born in Middlefield, a village in western Massachusetts, of English ancestry. The single son of five siblings, his parents were farmer Ebenezer and Mary Mack Emmons. The Reverend Dr. Nathaniel Emmons, an uncle, was a preacher of some note. At an early age, Emmons's interest in natural science became apparent. He received most of his training for college from the Reverend Moses Hallock, a teacher in nearby Plainfield. In 1814 he enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., where he further developed his interest in natural science under Amos Eaton, who introduced geology into the curriculum at Williams, and Chester Dewey, who initiated the teaching of chemistry there. Emmons was graduated in 1818 and the same year married Maria Cone of Williamstown.

In 1824 Emmons continued his studies in geology at the new Rensselaer (Polytechnic) Institute, where Eaton had become senior professor. Also that year he assisted Dewey in producing a geological map of Berkshire County, Mass. Emmons was graduated from the institute and published his Manual of Mineralogy and Geology, a handbook for students, in 1826.

Emmons pursued a vigorous tripartite career for over a decade. Apparently between his days at Williams and Rensselaer, he had studied medicine at the Berkshire Medical College and become a practising physician in Chester, Mass. Nevertheless, he continued to pursue his work in academic science. In 1828 he returned to Williams College as lecturer in chemistry while continuing an extensive medical practice. Two years later he accepted an appointment as junior professor at Rensselaer, a post he would hold for nine years. Meanwhile, he began to enlarge the cabinet of mineralogical and geological specimens at Williams and gave lectures at the Medical School of Castleton. His position at Williams was expanded in 1833 to a professorship of natural science, which he would retain until 1859. In 1838 he was named professor of chemistry in the Albany Medical College and moved to Albany; his association with that school, later in obstetrics, lasted until 1852. During that period he remained on the faculty of Williams College and traveled annually to Williamstown for his classes.

In 1836, Emmons became one of the four head geologists of the new geological survey for the state of New York. His territory included the northeastern counties, and he acquainted the public with the Adirondack region and named its principal mountains. He also named, described, and classified the Potsdam sandstone and other rocks. Of the latter, Emmons caused a great furor among geologists when he discovered and proposed the presence of a system of stratified rocks, which he named the Taconic system, beneath the Potsdam. The controversy would not subside for decades, and Emmons reportedly became embittered by the ostracism and ridicule of other geologists who refused, at times contemptuously, to accept the Taconic theories. The state published his geological report in 1842, and he took charge of the collections of the geological survey. He subsequently investigated the agricultural resources of New York. The work resulted in five volumes (1846–54) dealing with topography, climate, agricultural geology, the Taconic system, soils, grains, vegetable products, fruits, and harmful insects in New York.

In the meantime the legislature of North Carolina in 1851 revived the state geological survey, defunct since 1827. In January 1852 Emmons became its chief, a position he would fill until his death. Indefatigable, Emmons himself did much of the field, office, and laboratory work. He guided most of the efforts toward development of mining, minerals, and agriculture yet undertook very little work west of the Blue Ridge. The state in 1852 published his Report of Professor Emmons on His Geological Survey of North Carolina, which dealt chiefly with the agriculture and geology of the eastern counties and the coal fields by the Deep River. Emmons's Geological Report of the Midland [Piedmont] Counties of North Carolina, which appeared in 1856, contained a discussion of the geology of the area, a view of the coal fields, and wide-ranging comments on deposits of gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, and manganese. Two years later he produced a lengthy volume on agriculture of the eastern counties centering around soils, fertilizers, marls, and fossils found in the marls. In 1860 he prepared shorter studies on the principles and practice of agriculture in the state as well as analyses of soil from swamp lands. Under his direction, botanist Moses Ashley Curtis wrote two volumes on descriptive botany of the state, and agriculturalist Edmund Ruffin prepared a description of the agriculture and geology of lower North Carolina. During these busy years, Emmons also found time to publish a major book on American Geology and, in 1860, a brief text and manual on the subject. In addition, he served as private consultant to individuals involved in mining metals in the state.

The Civil War shattered Emmons's life and much of his work. Loyal to the Union, he was caught in the South. Anxiety and separation from friends probably fostered the ill health that eventually confined him to his home in Brunswick County, where he died in 1863. He was buried in the City Cemetery, Raleigh, but his remains later were moved to Albany, N.Y. During the war much of the work of Emmons and his assistants was lost, including personal papers (after his death), cabinets of minerals and fossils, manuscript geological maps, and written manuscripts sufficient for several volumes. The conflict interrupted the regular work of the geological survey, and his successor's task was to look after the manufacture of certain war products.

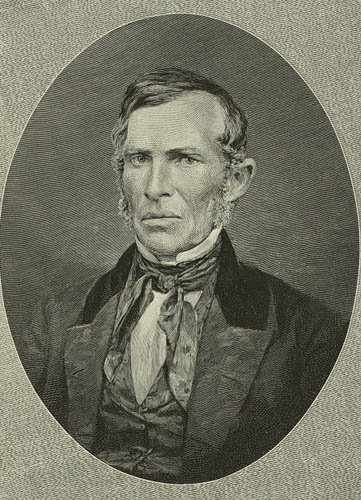

A persevering and enthusiastic worker and teacher, Emmons reportedly was an able man with a kindly yet distant disposition. A religious man, he had served as a deacon in Williamstown. His portrait is preserved in books by Stuckey and Youmans cited below. Emmons had a son, Ebenezer, Jr., and two daughters, Amanda (Conklin) and Mary (Watson).