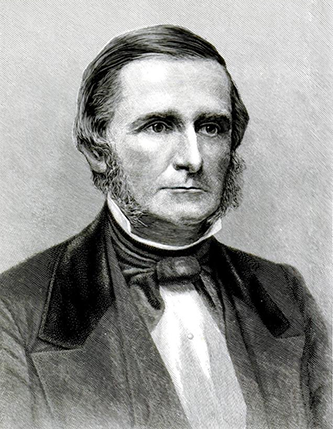

11 May 1808–10 Apr. 1872

Moses Ashley Curtis was a priest, teacher, botanist, enslaver, and mycologist. He was born in Stockbridge, Mass., the son of Jared and Thankful Ashley Curtis. His earliest education was received under his father, who was principal of Stockbridge Academy; he was graduated from Williams College in 1827. The University of North Carolina in 1852 conferred upon him the D.D. degree.

For two years after college graduation, Curtis taught in local schools, but in 1830 he became a tutor in the family of Edward B. Dudley in Wilmington. As a college student, young Curtis had been interested in the natural sciences, and in Wilmington he joined Dr. James F. McRee in the study of local plants. In 1833, however, he returned to Massachusetts and in Boston began the study of theology under the rector of the Church of the Advent; this study was continued the following year in Wilmington, apparently under the direction of the Reverend Thomas F. Davis, rector of St. James's Church. On 3 Dec. 1834, Curtis and Mary Jane de Rosset of Wilmington were married. In due course, Curtis was ordained to the Episcopal priesthood and served various churches in North Carolina, including, in his early years, Lincolnton, Salisbury, Morganton, and Charlotte.

In January 1837, Curtis went to Raleigh to teach in the Episcopal School for Boys, a predecessor of St. Mary's Junior College. Financial conditions at the school were such that, instead of receiving proper compensation for his labors, it developed that he was in large measure supporting the school. In 1840, having sold many of his personal possessions to satisfy creditors of the school, he departed for service as a missionary in the vicinity of Washington, Beaufort County. He accepted a call to St. Matthew's Church, Hillsborough, in June 1841 and remained at the post for the remainder of his life, except for the years 1847–56, which were spent in Society Hill, S.C.

Curtis, through some strength of spirit almost beyond comprehension, led two nearly separate but equally full lives. He was a devout and unselfish priest and teacher on the one hand. On the other he was a knowledgeable scientist, and the judgment of those who followed him in his chosen field of mycology acclaim him as a keen observer and a pioneer discoverer of many American plants. These were not the only fields in which he excelled. As a musician he was appreciated by a wide circle of friends throughout the state, with whom he played on many occasions. The piano, flute, and organ were his principal instruments; but he also played the violin. He sometimes served as church organist and frequently trained his choir to sing such works as Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus," Mozart's "Gloria," and Haydn's Creation. Whenever possible he attended concerts, particularly when he happened to be in Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, and his comments on them indicate a cultivated appreciation of good music. He also composed hymns and anthems. One of his compositions, "How Beautiful upon the Mountains," was written for his own ordination. Curtis was also in demand as a lyceum speaker, and manuscripts of some of his lectures, a poster, and clippings of lecture advertisements from the years before the Civil War survive in his papers. As a linguist, he was unusually well trained. He is said to have known German, French, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. For his own convenience he frequently made notes in shorthand, and he employed shorthand symbols in letters to members of his family.

The Curtis children were William White (1838–43), Armand de Rosset (1839–56), Moses Ashley (1842–1933), John Henry (1844–65), Katharine Fullerton (1845–1922), Charles Jared (1847–1931), Mary Louisa (1849–1929), Magdalen de Rosset (April–September 1851), Caroline (1852–62), and Elizabeth de Rosset (1854–1928). Curtis was a devoted husband and father and while away from home observed strict "writing days." He frequently took his children with him on trips through the state as well as to the North. Until the Civil War intervened, he wrote regularly to his father and even managed to get some communications to him under a flag of truce during the war. News of the death of the elder Curtis reached him in 1862, through the kindness of a Union chaplain in occupied New Bern. The war was a particularly sad occasion for Curtis for a number of reasons. Although born in New England, he came from an enslaving and slaveholding family. His sympathies lay wholly with the South, and one of his sons was killed at the Battle of Bentonville in 1865. Curtis had a book almost ready for the press when the war began, but it was never published. His contact with fellow churchmen and scientists throughout the country and abroad was suddenly cut off.

Wherever Curtis was he was interested in local plants. His first parish in Lincolnton provided ample opportunity for collecting specimens, and from his missionary journeys he always returned with well-filled portfolios. Some of his parishioners even caught the spirit and began to collect and press plants for him. It may have been his familiarity with the mountain region that brought him an assignment to the committee charged with selecting a site for the University of the South in 1857. This was an undertaking of the church of which he heartily approved, and he took the lead in the mountaintop services when a site was chosen at Sewanee, Tenn.

Curtis was known at home as an Episcopal clergyman of unusual vigor, yet outside North Carolina he was known as a scientist. His interest may have been stirred at Williams College, where he knew Ebenezer Emmons and others with similar talent, but it flourished when he reached Wilmington, and from there he went botanizing into South Carolina and Georgia. His first report was published in the Journal of the Boston Society of Natural History in 1835, and in it he corrected much previous misinformation concerning the Venus flytrap. In his expeditions into the mountains he studied the relation of plant life to geologic and climatic surroundings. It was Curtis who first brought to the attention of the whole country the unique position of North Carolina in climate, soil, and forest products. He pointed out "that North Carolina has a difference of elevation between the east and west which gives a difference of climate equal to 10 or 12 degrees of latitude." Curtis was in close and frequent communication with leading botanists at home and abroad, including Asa Gray, H. W. Ravenel, William S. Sullivant, Edward Tuckerman, and A. W. Chapman (whose Flora of the Southern United States, published in 1860, was dedicated to Curtis). His national reputation was such that specimens collected by U.S. exploring expeditions were sent to him for study, identification, and report.

By 1846, Curtis had begun to express particular interest in the study of fungi. By the time of the Civil War he had made such an extensive investigation that he was a recognized authority in the field of mycology. During the war he undertook to prepare a work on "Esculent Fungi," for which his son, Charles Jared, prepared colored drawings. The book was completed but never published. In 1869, Curtis made the unchallenged claim that he had eaten a greater variety of mushrooms than any one on the American Continent. By carefully testing one species after another, he learned their quality as food and discovered that the flavor varied with the type of material in which the mushroom grew. Mushrooms growing in hickory and mulberry wood, for example, were found especially desirable. At one time during the war he asserted that he believed it possible to "maintain a regiment of soldiers five months of the year upon mushrooms alone." In partial support of this theory, he reported that he had collected and eaten forty species found within two miles of his own house.

Curtis contributed scientific articles to a variety of American and British journals and was the author of several books, including A Catalogue of the Plants of the State, With Descriptions and History of the Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines (Raleigh, 1860); A Catalogue of the Indigenous and Naturalized Plants of the State (Raleigh, 1867); and The Woods and Timbers of North Carolina (Raleigh, 1883).

Herbaria collected by Curtis are now at The University of North Carolina, Harvard University, the University of Nebraska, and the New York State Museum.

Curtis was buried in the yard of St. Matthew's Church, Hillsborough.