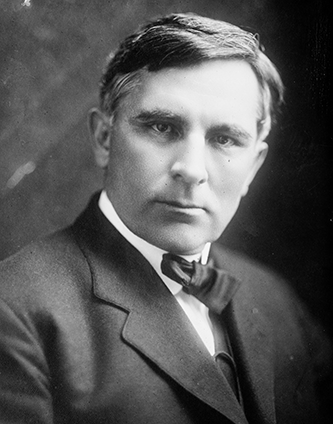

16 Aug. 1860–9 June 1924

See Also: Annie Craig, Locke Craig - Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Locke Craig, governor and legislator, was born in Bertie County of Scottish heritage. His paternal ancestors had come in 1749 from Ireland to Orange County, where they played an active role in the Revolution and afterward. His father, Andrew Murdock Craig, was a Baptist minister and scholar known for his cultivated tastes; his mother, Clarissa Rebecca Gilliam, was of an influential Bertie County family.

Craig, who was named for the English philosopher John Locke, grew up on the family farm in Bertie County. His mother, widowed shortly after the Civil War, sold the farm and accompanied him to The University of North Carolina when he was only fifteen. Scholarly from boyhood, he blossomed at Chapel Hill into an active student leader. Upon graduation at nineteen he was the youngest person ever to have gained his degree there; he was chosen commencement speaker for his oratorical skills. Among his classmates at the university was Charles B. Aycock, with whom in later years he would often share the stage in Democratic party struggles.

After graduation, Craig taught chemistry at the university briefly and for a time was a teacher at a private Chapel Hill school. In 1883 he moved to Asheville to set up a law practice. Thereafter, his home would always be in the mountains, and he was destined to become, after Zebulon B. Vance, that section's most eloquent political spokesman. Though he was short in stature, his fine features and commanding voice were impressive; in later years he would be known throughout the state as the "Little Giant of the West."

As his law practice grew, Craig began to take an active part in the local Democratic party. In 1892 he was chosen Democratic elector for the Ninth Congressional (Cleveland) District; in 1896, as elector-at-large, he canvassed the state for William Jennings Bryan and drew many large crowds with his oratory. Throughout the late 1890s he was in the forefront of the Democratic fight to wrest state control from the Fusionists, who had gained power with a stunning upset in the 1894 elections. Before the 1898 elections, he took part, together with Aycock, Furnifold M. Simmons, and others, in a memorable speech-making campaign directed against the Fusionists. On 10 May 1898 at Laurinburg, a joint speech given by Aycock and Craig ignited the so-called white supremacy campaign. The Democrats, after a bitter struggle, won victory at the polls and regained control of both houses of the legislature. Craig was elected to the legislature from Buncombe County in 1898 with a seven-hundred-vote majority, reversing a previous Republican majority of six hundred.

In the 1899 legislature, Craig was one of a group of Democrats who formulated the "grandfather clause," a constitutional amendment proposing educational requirements for voters but exempting those whose ancestors (prior to 1867) were qualified voters. In the 1900 elections the amendment was passed by the voters, and the Fusionist governor, Daniel Russell, was defeated by Aycock.

Craig had been a firebrand in the fight to overthrow Fusionism, and thereafter his high status in the party was assured. He continued in the legislature but, though actively supported, lost two attempts at higher office. In 1903 he sought to become U.S. senator, but Lee S. Overman was chosen the party nominee. In 1908 he made a determined bid for the governorship, but a close, three-way race among Craig, W. W. Kitchin, and Ashley Horne resulted in a deadlock after three days of speeches and balloting. When Horne bowed out, Craig in turn conceded graciously to Kitchin. It became a foregone conclusion that Craig would be next in line for the governorship, and at the 1912 convention he was nominated by acclamation.

His administration, which began on 15 Jan. 1913 and comprised the four years immediately before World War I, carried forward the educational reforms of Aycock and initiated several programs of its own. Public school districts were consolidated; four months' attendance was made compulsory for children aged eight through twelve; and local taxation for school support was encouraged. Transportation advanced, with the appointment of the first highway commission. A program of road building, which led ultimately to North Carolina's national recognition as the "Good Roads State," was begun: five thousand miles of state-built roads in 1913 grew to fifteen thousand miles by 1917.

The problem of railroad freight rates was alleviated by reducing the rates to the level of the rest of the South. This move spurred manufacturing and economic development, as state merchants were saved an estimated $2 million in shipping charges. Industry was also helped by the harnessing of electric power from several of the state's rivers, including the Yadkin, Catawba, French Broad, and Cape Fear.

The Craig administration was noted for its humanitarianism. State-supported health and welfare institutions were founded, and private endeavors were encouraged. The prison system returned a net profit of four hundred thousand dollars after the state contracted to have prisoners perform road and railroad labor. A part of prisoners' earnings were returned to their families. Executive clemency was invoked often, and many pardons were issued.

The administration was particularly sensitive to the needs of the western part of the state. Road building through the difficult mountains was encouraged. The land around Mount Mitchell, the highest peak in eastern America, was purchased in 1915, and a state park was founded there. Craig served on the Appalachian Park Commission, which promoted Pisgah National Forest. In 1916, when great floods ravaged the western areas, he acted decisively; a state relief committee was formed, and through public and private contributions the effects of the disaster, the worst flooding the mountains had then seen, were brought under efficient control.

The Craig administration was in general prosperous and progressive, continuing the reforms begun under predecessors Aycock, Glenn, and Kitchin. It has been remarked that the state progressed more in the years 1900 to 1917 than in the previous hundred years, and Craig's governorship played a large part in that achievement.

When his term ended, he retired to his home on the Swannanoa River and to his law practice. In declining health, he was looked on as an elder statesman and treated almost reverentially by his mountain neighbors. He was buried in Asheville at Riverside Cemetery.

A lifelong Baptist, Craig was married in 1891 to Annie Burgin of McDowell County. The couple had four sons, Carlyle, George, Arthur, and Locke, Jr. On 16 Oct. 1944 a portrait by Asheville artist Cuthbert Lee was unveiled at presentation ceremonies in the senate chamber of the capitol at Raleigh.