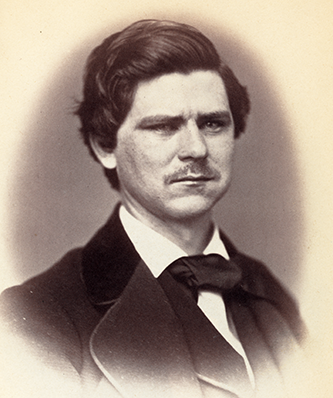

13 May 1830–14 Apr. 1894

See also: Zebulon Baird Vance, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Zebulon Baird Vance, Confederate soldier, governor of North Carolina, congressman, and U.S. senator, was the third child and second son of David and Mira Baird Vance. He was born in the old homestead in Buncombe County, on Reems Creek, about twelve miles north of Asheville. After attending the neighborhood schools, he enrolled in 1843 (at age thirteen) in Washington College, near Jonesboro in eastern Tennessee, but withdrew the next year on the death of his father, who left a widow and seven children. In search of better educational opportunities Mrs. Vance moved to Asheville and put her children in school there. In 1850 Vance read law briefly under John W. Woodfin and in July 1851 arrived at The University of North Carolina to continue his legal studies. The next year, after being licensed to practice in the state's county courts, he returned to Asheville and was immediately elected solicitor for Buncombe County. In 1853 he was admitted to practice in the superior courts. Yet law never brought forth his best endeavors. For Vance law was primarily preparation for politics, which was his passion. Success in the courtroom was usually the result of wit, humor, boisterous eloquence, and clever retorts, not knowledge of the law. He understood people better than he did judicial matters.

Vance entered North Carolina politics as a Henry Clay Whig but on the dissolution of his party aligned himself with the American or Know-Nothing party. In 1858, after serving one term (1854) in the lower house of the North Carolina legislature, he was elected to the Thirty-fifth Congress to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Thomas L. Clingman. He also won a seat in the Thirty-sixth Congress (1859–61), the last before the disruption of the Union.

Vance never questioned the legality of secession, only its wisdom under certain circumstances. In fact, his was a powerful voice in behalf of union up to the firing on Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln's call for troops. These were the circumstances that changed his plea from that of union to that of secession.

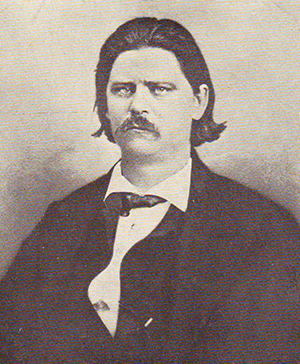

Refusing all overtures to be a candidate for the Confederate Congress Vance raised a company of "Rough and Ready Guards" and on 4 May 1861 marched off to war with a captain's commission. By June the "Guards" had become Company F, Fourteenth North Carolina Regiment, and were on duty in Virginia. In August Vance was elected colonel of the Twenty-sixth North Carolina, which he ably led in battle at New Bern in March 1862 and shortly afterwards in the Seven Days fighting before Richmond.

Although Vance was a good combat officer, he could not remove himself completely from politics. Thus he gladly accepted the Conservative party nomination for governor in 1862. The Conservatives, composed primarily of old-line Union Whigs, were led by W. W. Holden, editor of the North Carolina Standard and a bitter critic of President Jefferson Davis. The Confederate party, as the Democrats called themselves, selected "original secessionist" and railroad executive William Johnston of Mecklenburg County. The result was an overwhelming victory for Vance but not a verdict for reunion. It was more an expression of dissatisfaction with state and Confederate leadership and trying war conditions.

As war governor Vance worked hard to provide North Carolina troops and civilians with necessary arms, clothing, and food. At the same time he strongly defended the wartime rights of the state and its citizens. These efforts endeared him to his own people but oftentimes brought him into sharp dispute with the Davis administration. Vance objected strenuously to the Confederate conscription and impressment of property laws, the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, discrimination against North Carolinians in the appointment and promotion of commissioned officers, and the use of Virginia officers in the state.

Other controversies between the governor and Richmond centered around North Carolina's efforts to clothe its troops in the Confederate army and its ownership of blockade-runners. But there were no quarrels with Confederate officials when the governor turned his attention to the difficult task of returning army deserters to the ranks. Instead, Vance found himself in conflict with Chief Justice Richmond M. Pearson of the state supreme court who discharged many defendants on the grounds that the governor had no authority to arrest either deserters or recusant conscripts.

Disaffection in North Carolina manifested itself not only in desertion and draft evasion but also in the peace movement of 1863–64 led by Holden. Fearful of this development, Vance denounced it strongly and then broke with his erstwhile political ally. Thereupon Holden announced his candidacy for the governorship in 1864. The gubernatorial race of that year was a bitter one, but Vance won by a very convincing majority. From the moment of his reelection until the end of the war the next spring the governor worked untiringly for the Confederate cause. In early 1865 he refused to cooperate with a group in the Confederate Congress calling for peace on the basis of separate state action. However, on 10 April, having been informed that Confederate troops of General Joseph E. Johnston would soon have to evacuate Raleigh, Vance began the transfer of state records and military stores to Graham, Greensboro, and Salisbury. Two days later, with the capital unprotected and William T. Sherman's army rapidly advancing on the city from the east, he sent ex-governors David L. Swain and William A. Graham to open negotiations with the Union general. When the commissioners failed to return at the appointed time, late afternoon, the governor decided to leave Raleigh, which he did around midnight. After spending the remainder of the evening at General Robert F. Hoke's camp about eight miles from the city, he proceeded to Hillsborough and from there to Greensboro and thence to Charlotte by rail to talk with President Davis. Vance then returned to Greensboro. He was there when it was announced that General Johnston on 26 April had surrendered his forces to Sherman at the James Bennett farmhouse near Durham. On receipt of this news the governor issued his final proclamation to the people of North Carolina and then surrendered himself to Union general John M. Schofield. The general, having no orders for Vance's arrest, told him to go to Statesville, where Mrs. Vance and their children had sought safety. But early on the morning of 13 May the governor was arrested at his Statesville home. It was his thirty-fifth birthday. He was sent to Washington, D.C., and on the twentieth placed in the Old Capitol Prison where he remained until paroled on 6 July. No reason was ever given for his forty-seven-day imprisonment, and no charge was ever brought against him.

On 3 June 1865, in compliance with President Andrew Johnson's amnesty proclamation of 29 May and while still in prison, Vance filed an application for pardon. It was granted on 11 Mar. 1867. In the meantime he had returned to North Carolina and formed a law partnership in Charlotte. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1870, but due to the disabilities placed on ex-Confederates under the Fourteenth Amendment he was unable to take his seat in Congress. Later freed of political encumbrances, Vance accepted the Democratic (formerly Conservative) nomination for governor in 1876. His Republican opponent, Judge Thomas Settle of Rockingham County, was a very able man. The candidates agreed on a joint stumping tour of the state beginning at Rutherfordton in late July and lasting for three months. The debates, combined with the partisan bitterness of the times, made the campaign one of the most dramatic political contests in North Carolina history. Huge crowds gathered at campaign stops. Vance won, but his margin of victory was narrow. His third term as governor was noteworthy not only because it marked the end of Reconstruction in the state but also because of gains made in public education and railroad building.

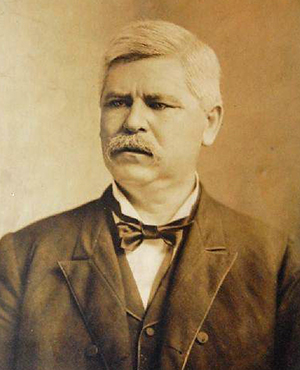

Vance served only two years of his four-year term, as he was elected to the U.S. Senate by the General Assembly in 1878 on the expiration of A. S. Merrimon's term. Reelected in 1885 and 1891, he held his seat until his death. During his senatorial career Vance stoutly defended the interests of the South but at the same time harbored little bitterness towards the North. It was his misfortune, however, to be known as an opposition senator. He resisted much of the important legislation of the period, and no constructive enactment of the Senate is associated with his name.

Vance's health began to fail in 1889 with the removal of one of his eyes. He died five years later of a stroke at his home in Washington. He was buried in Asheville. Vance was married twice. His first wife, Harriette Espy of Quaker Meadows, Burke County, whom he married on 3 Aug. 1853, bore him five sons: Robert Espy (b. 1854, died young), Charles Noel (b. 1856), David Mitchell (b. 1857), and Zebulon Baird, Jr. (b. 1860). Robert Espy is often left out of biographies due to his infant death but is mentioned in letters between Zebulon and Hattie and in their family bible. Hattie died in 1878. In 1880 he married a widow, Florence Steele Martin of Louisville, Ky., who survived him. They had no children.

Vance's engaging personality and lengthy public career gained for him an admiration from North Carolinians that no other state official has ever enjoyed. To the multitude especially he was a beloved leader. Ex-Confederate soldiers and their families were not quick to forget his efforts to care for them in time of war and how he defended their liberties and preserved their honor. As his funeral train moved westward through the state, thousands of humble people lined the tracks to pay their last respects to one whom they loved and admired very much.