Union or Disunion? North Carolina Votes for Secession

by Robert Tinkler

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 1996.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See Also: Secession Movement; Women- Part 5: Secession and Civil War

John Steele Henderson was fourteen years old when the Civil War began, in April of 1861. A native of Salisbury who attended a boarding school in Alamance County, John grew up in a wealthy, slaveholding family with a tradition of public service. His relatives included distinguished civic leaders.

John Steele Henderson was fourteen years old when the Civil War began, in April of 1861. A native of Salisbury who attended a boarding school in Alamance County, John grew up in a wealthy, slaveholding family with a tradition of public service. His relatives included distinguished civic leaders.

John keenly observed the series of events that unfolded from the fall of 1860 through the spring of 1861, events that made up the final chapter of North Carolina’s antebellum history. His commentary provides an account of North Carolina’s controversial decision to leave the Union and go to war.

Sectional Conflict

Of course, the conflict between North and South that led to the Civil War had begun long before the fall of 1860, even years before John’s birth in 1846. The war resulted from the inability of northerners and southerners to resolve their differences over important issues in a peaceful, permanent manner.

Tariffs created difficulties between the North and the South in the 1820s and 1830s. Northerners wanted to place high tariffs on manufactured goods, like textiles, that were imported into the United States from Europe. Goods from Europe would then be at least as expensive as goods made in this country. Therefore, Americans would be more likely to buy goods made in the United States. Since the North was more industrialized and had more finished products to sell than the South, the North would benefit from tariffs more than the South. Most southerners did not like tariffs. The South, which grew more raw materials and had fewer industries that processed and sold finished products, preferred to buy from Europeans, who were better customers for southern-grown cotton, tobacco, and rice. As complicated and divisive as the tariff question was, however, another issue proved to be the most divisive problem between the North and the South.

In the first half of the 1800s, as the United States added new territory west of the Mississippi River, one question kept cropping up: Should slavery be allowed in these new lands? Many northerners said, “No”—some for moral or religious reasons, and others for economic reasons. They did not want to compete for work with the low cost of slave labor in the territories. Southerners, though, argued that they had a right to take any of their property, which included slaves, wherever they liked. For a time, politicians from the North and South worked out deals in Congress that basically ignored the issue and satisfied enough people on both sides to quiet any open conflict.

In the 1850s, though, these compromises unraveled. Some slaveholding southerners insisted on their ideas more loudly—they insisted that they had the “southern right” to take their property, their slaves, into new territories. Meanwhile, a minority of northerners urged the immediate abolition, or total elimination, of slavery. Each side accused the other of being extremist and not listening to the other side’s views. When a new political party in the North, called the Republicans (but not the same party as the earlier Jeffersonian Republicans, or Democratic-Republicans), nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860, some southern-rights Democrats warned that his election would force their states to secede, or withdraw, from the Union. They believed the Republicans, who opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, really wanted to abolish it altogether, even in the South. John and his family indicated they were very suspicious of Lincoln. They favored secession.

Another group of southerners, called unionists, opposed secession. Unionists, who included some Democrats and most Whigs, believed that the best way to preserve slavery was to remain in the Union. Secession, they feared, would lead to a war that would destroy slavery. In North Carolina, unionist strength lay in areas with relatively few slaves like the Mountains and the Piedmont, including Alamance County, where John went to school. John’s teacher was a unionist, and he once reprimanded John for wearing a secessionist political button to school.

The Election of 1860

Lincoln was not on the ballot in North Carolina or most other southern states. In the South, the election really came down to a contest between a southern-rights Democrat, John Breckinridge of Kentucky, and unionist-supported John Bell, a former Whig from Tennessee. Breckinridge and Bell supporters flocked to political barbecues all around North Carolina that autumn. There, party spokesmen tried to excite audiences about their candidates. At a unionist barbecue in Graham, John heard speakers denounce Breckinridge leaders as "avowed traitors to the Union who would rather rule in hell than serve in heaven." A true Breckinridge supporter, John thought these speakers were as bad as the dinner they served: "beef, raw pork, and bread that actually wasn’t fit for dogs to eat."

In North Carolina, Breckinridge narrowly defeated Bell. But overall, Lincoln earned enough electoral votes in the North to win the White House. His election was all the reason secessionist politicians in South Carolina needed to declare their state out of the Union on December 20, 1860, barely a month after the election. Many other southerners, especially in areas with many slaves, wanted to follow South Carolina’s lead. Even though the new president would not take office until March 1861, these secessionists believed they had to act quickly.

Two weeks after Lincoln’s election, John W. Ellis, North Carolina’s southern-rights-Democrat governor, asked the legislature to call a convention of the people to discuss secession. But unionists like newspaper editor William Holden and congressman Zebulon Vance advocated a “watch-and-wait” approach. They believed that, rather than seceding based on fears of what Lincoln might do, southerners should hold off any action until they saw what the new president actually did.

A New Year

Events in other southern states affected the debate in North Carolina. In January, secessionists took heart as five lower South states followed South Carolina out of the Union. Also, the Virginia legislature passed a bill calling for a secession convention, which led John to observe that it was “far ahead of the Old North State.” On January 29, North Carolina’s convention bill passed in the General Assembly. The bill provided that voters would get to decide whether a convention would be called. In the late February election, unionists defeated the convention measure by about 650 votes out of nearly 94,000 cast. North Carolina was not yet in favor of secession.

"North Carolina has disgraced herself," John wrote bitterly. "I don’t know how she can secede now, she has refused to call a convention, which will for ever be a stain upon her name." His father was considering moving from North Carolina, and John, disgusted with his home state’s unionism, was glad to hear it.

When Lincoln took office, he tried to reassure slaveholders in North Carolina and other slave states still in the Union that he would not touch slavery in the South. John was unconvinced. He thought Lincoln gave "a very poor inaugural address, I believe I could do better than that myself. I could make nothing out of it, but nonsense." Unionists, however, welcomed Lincoln’s words as proof of the wisdom of their "watch-and-wait" policy.

The Final Moments

Just before dawn on April 12, 1861, armed forces of the new Confederate government fired on Union soldiers stationed at Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Many unionists had hoped Lincoln would withdraw these troops to avoid such an attack, but the fort had instead become a symbol of the Union’s resolve, and Lincoln had refused to abandon it.

Just before dawn on April 12, 1861, armed forces of the new Confederate government fired on Union soldiers stationed at Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Many unionists had hoped Lincoln would withdraw these troops to avoid such an attack, but the fort had instead become a symbol of the Union’s resolve, and Lincoln had refused to abandon it.

Upon first hearing of the attack, John did not "believe a word of it." When confirmation came, John and his friends decided to "hoist a Secession flag" near their school. A skirmish with their unionist schoolmaster followed. The teacher ordered the boys to disperse, and he struggled unsuccessfully to lower the flag. During the night, the boys fired a twenty-one-pistol salute to honor the Confederacy and moved their flag to a more prominent location in town. The boys at John’s school even formed a militia to "drive the Abolitionists from the soil of the South."

Lincoln responded to the Fort Sumter attack by calling for volunteers from all the states in the Union, which still included North Carolina, to put down the "rebel" Confederates. Even many unionists thought the president had now gone too far. They could never agree to use force against their fellow southerners. "There has been a great change in opinion in Alamance," John reported excitedly. "Everybody about here is for Secession."

Many unionists, thinking secession inevitable, stayed home as North Carolinians approved a convention in mid-May. When the delegates met in Raleigh on May 20, they voted unanimously to secede from the United States and to join the Confederate States of America.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: To Secede or Not to Secede: Events Leading to the Civil War. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. https://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/seccession.pdf

Grade 5: To Secede or Not to Secede: Events Leading to the Civil War. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/seccession.pdf

Image credits:

Currier & Ives. 1861. "South Carolina's 'ultimatum.'" Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction no. LC-USZ62-17261. Online at

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003674566/

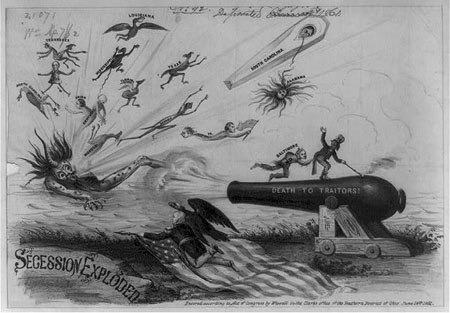

Wiswell, William. 1861. "Secession Exploded." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction no. LC-USZ62-89738. Online at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661629/

References and additional resources:

John Steele Henderson papers. 1755-1945, 1962. UNC Libraries, Southern Historical Collection. http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/h/Henderson,John_S.html

Learn NC resources on secession.

Sloan, John Alexander. 1883. North Carolina in the war between the states. Washington: Rufus H. Darby, Publisher. Online at https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/north-carolina-in-the-war-between-the-states/576268?item=691384

UNC Libraries, Documenting the American South resources on secession.

1 January 1996 | Tinkler, Robert