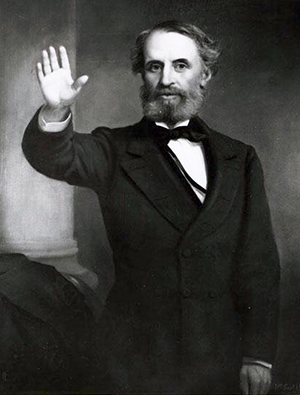

27 July 1812–3 Nov. 1897

Thomas Lanier Clingman, antebellum political leader, Civil War general, and propagandist for Western North Carolina development, was born at Huntsville in Surry (now Yadkin) County. His grandfather, Alexander Clingman, had immigrated to Pennsylvania from Germany in the mid-eighteenth century and had come shortly thereafter to the western part of North Carolina. Thomas's father, Jacob Clingman, established himself as a merchant at Huntsville and married Jane Poindexter, whose ancestry included French and Scottish blood and a great-grandfather who was a Cherokee chieftain. Jacob Clingman died when his son was four years old, leaving Thomas to be reared and educated by his mother and an uncle, Francis Alexander Poindexter. In 1829, Thomas Clingman entered The University of North Carolina as a sophomore, graduating in 1832 at the head of his class. Despite an illness that threatened his sight, he read law at Hillsborough under William Alexander Graham, at that time one of the leading lawyers in the state.

The year 1835 marked Clingman's entry into politics. Shortly after being admitted to the bar, he was elected from Surry County to the lower house of the North Carolina legislature. There he quickly allied himself with the newly formed Whig party, which was pushing for a revision of the North Carolina Constitution in the interest of more equitable representation for the western part of the state. His bid for reelection in 1836 was unsuccessful. Lured by the prospects of future development of the North Carolina mountain region, he soon moved to the vicinity of Asheville in Buncombe County, the area with which he identified himself for the remainder of his life.

In 1840, after practicing law for four years, Clingman was elected to the state senate, where he served only one term. In 1843 he sought and gained election to the U.S. House of Representatives; with the exception of the 1845–47 term, he remained in Congress as representative or senator until the beginning of the Civil War. He served in the House until 1858, when he was appointed senator to fill the unexpired term of Asa Biggs. In 1860 he was elected to the Senate for a term in his own right, and he was the last southern senator to leave the Congress in 1861.

Clingman entered the Congress in 1843 as a rabid Whig partisan. His adherence to national Whig policies in opposing the annexation of Texas and the Gag Rule, directed against abolitionist petitions, was, in fact, to cost him his seat in 1845. During his first term in Congress his denunciations of Democrats and Democratic policies were so vehement that they led to a duel with Democrat William L. Yancey of Alabama. The conflict was resolved with apologies after both combatants had fired and missed.

Increased agitation over the slavery issue and the question of southern rights, precipitated by the Mexican War, led Clingman to break with the Northern-dominated Whig party after his reelection to Congress in 1847. Though nominally a Whig until 1852, he drifted gradually toward the Democratic party and its representation of southern interests. Preferring to chart his own course, however, he never became an adherent of John C. Calhoun's effort to form a sectional party in Congress. Clingman opposed the Compromise of 1850, voting only for the Fugitive Slave Law. In 1852, along with thirteen fellow southern Whigs, he withdrew from the Whig Caucus when it refused to support the addition to the Whig Platform of a southern endorsement accepting as final the compromise measures and the Fugitive Slave Law. By 1854, when he backed the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Clingman had moved definitely into the Democratic fold. He continued to represent what he regarded as the interests and constitutional rights of the South until his withdrawal from the Senate at the onset of the Civil War.

In the Confederacy, Clingman served briefly as a commissioner to the provisional government at Montgomery. Though he had no military experience, he was commissioned in September 1861 as colonel and head of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina Regiment; in August 1862 he was made a brigadier general. He served without special distinction in Eastern North Carolina and Virginia, taking part in the Battle of Cold Harbor in Virginia near the end of the war.

After the war, Clingman was prohibited from returning to politics by the amnesty provisions. Consequently, he turned to a career as a propagandist for Western North Carolina development. He lectured and wrote extensively about the mountain region and continued scientific studies of the area begun before the war. In the 1850s he had engaged in a running dispute with Dr. Elisha Mitchell of The University of North Carolina about the location of the highest peak in the Black Mountain range. Ultimately, Mitchell's name was given to the highest mountain in the range and Clingman's was given to another peak on the same ridge. The highest peak in the Great Smoky Mountains was also named for him (Clingman's Dome). After the war his studies focused on the geology of Western North Carolina and on experiments dealing with meteors and the height of the atmosphere. His only roles in postwar politics were services as delegate to the constitutional convention of 1875 and to the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis in 1876. He continued to lecture widely until his health failed him in his last years.

Clingman, who never married, died at Morganton; he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville.