See also: Guilford Courthouse, Battle of; Loyalists; Moore's Creek Bridge, Battle of; Resolves, Prerevolutionary; Rutherford's Campaign; The Transylvania Purchase and the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: First North Carolina Conflicts and the Establishment of a Provincial Government; Part iii: North Carolina's Role in the Continental Congresses; Part iv: Conflict with the Cherokees and British Invasion of the South; Part v: Gen. Nathanael Greene and the Battle of Guilford Courthouse; Part vi: A Troubled Aftermath; Part vii: References

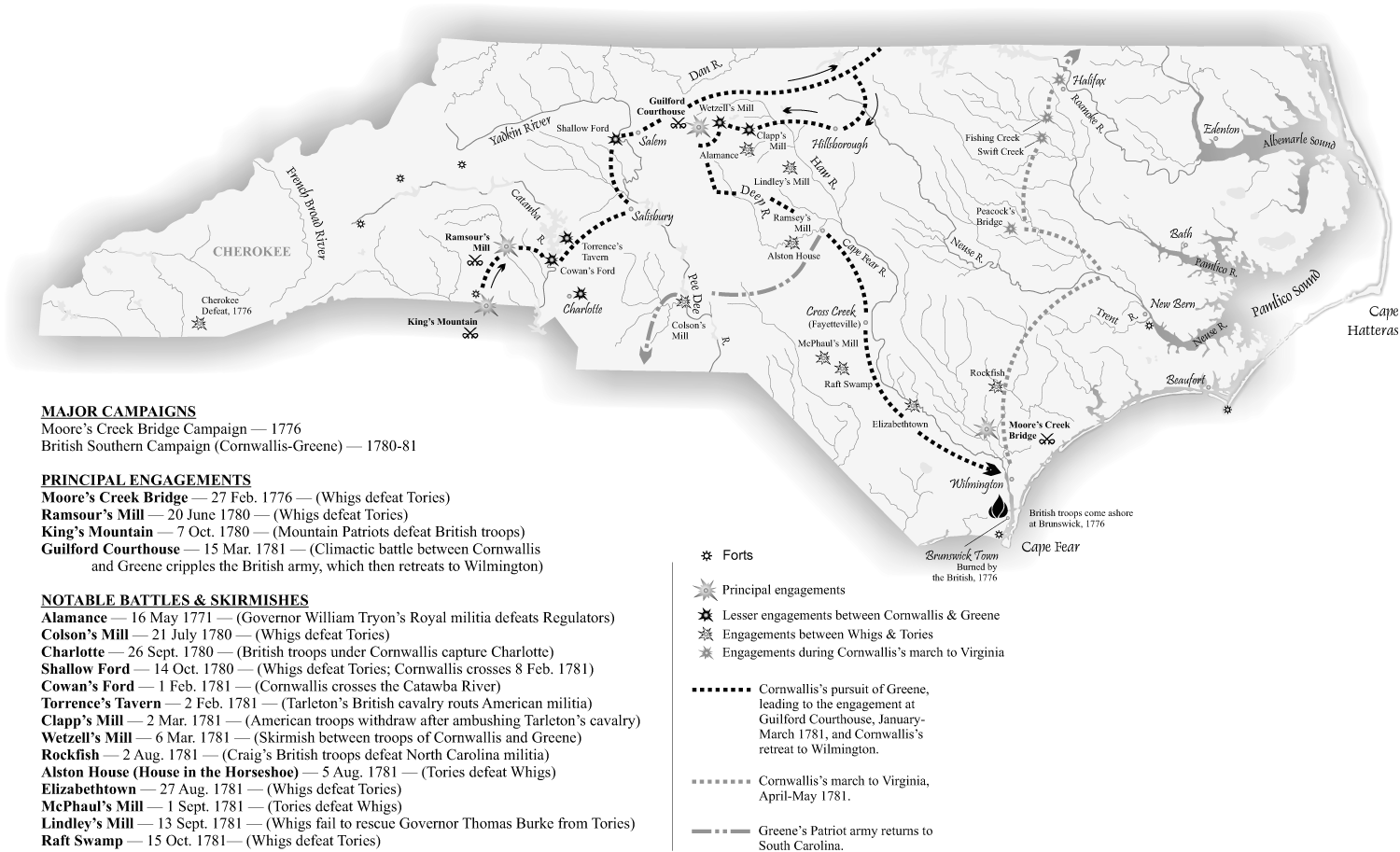

North Carolina witnessed little fighting within its boundaries from 1776 to 1780, with one exception. The Cherokee Indians in the western part of the colony were compelled to join forces with the British, who had promised to remove American encroachers from Cherokee land and, ultimately, to ensure greater tribal independence. In response to Cherokee attacks on Americans living in the western frontiers of North Carolina and Virginia, Gen. Charles Lee, commander of the Continental forces in the South, organized a coordinated attack on the Cherokee towns that populated the region. In the summer of 1776 Gen. Griffith Rutherford and 2,400 troops, backed by soldiers from Virginia and South Carolina, marched on Cherokee towns and settlements in western North Carolina. There, they left town after town devastated and many survivors without basic necessities such as clothing or food. Burning, looting, and pillaging by state militias were commonplace. The Cherokees finally surrendered and on 20 July 1777 signed the Treaty of Long Island, in which they agreed to cede lands to the Americans and promised not to resume fighting.

Frustrated by their unsuccessful attempts to defeat America's Gen. George Washington in the North, the British in 1778 undertook a new strategy of crushing the independence movement in the South. Gen. Robert Howe, the highest-ranking North Carolinian in the Continental Army, was commander of the entire Southern Department. When the British unleashed a powerful assault on Georgia in December 1778, however, Howe's defensive measures were inadequate. Savannah was the first major southern town to fall into British hands, with the rest of Georgia quickly following. Howe was later court-martialed and forced to resign over his failure to protect the state.

The British next moved into South Carolina, which fell in turn. The loss of Charles Towne (now Charleston, S.C.) led to the surrender of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln and his entire Patriot army, which included 815 Continentals and 600 militiamen from North Carolina. Now nothing stood in the way of a British invasion of North Carolina. Governor Richard Caswell (1776-80) and his successor, Abner Nash (1780-81), worked feverishly to prepare to meet the enemy forces, which were now commanded by Lord Charles Cornwallis. Caswell was placed in charge of the state's entire military force by the North Carolina General Assembly.

Although British victories in Georgia and South Carolina bolstered the spirits of North Carolina Loyalists, the defeat of the Tories at Ramsour's Mill (near present-day Lincolnton) and at Hanging Rock, S.C., impeded Cornwallis's efforts to subdue South Carolina and necessitated an invasion of North Carolina. The Continental Congress had tapped Gen. Horatio Gates, hero of the Battle of Saratoga, as the man to stop Cornwallis. On 25 July 1780 Gates arrived at Hillsborough and assumed command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. Gates led his 3,000 Continentals and 1,200 raw militia troops, under Caswell and Rutherford, on a poorly planned march to Camden, S.C. The troops had inadequate food, and many became ill on the long and difficult journey. On 6 August Gates and Cornwallis fought the Battle of Camden, with disastrous results for the Americans. Many of the raw North Carolina militiamen panicked and fled the battlefield. The Continentals suffered 800 dead and 1,000 captured. Gates was forced to retreat to Charlotte and then back to Hillsborough as Cornwallis prepared to launch his long-awaited invasion of North Carolina.

On 28 Sept. 1780 Cornwallis and his army entered Charlotte. North Carolina militia forces, led by Col. William R. Davie, harassed the British but could not stop them. Cornwallis was accompanied by the exiled Josiah Martin, who was so anxious to be reinstalled as royal governor of North Carolina that he almost immediately proclaimed the restoration of British rule. But Martin's announcement was premature. The people of Charlotte and the surrounding area did not welcome the return of royal rule, as the British had hoped they would. In addition, a 1,100-man Tory force led by a British regular, Maj. Patrick Ferguson, was defeated by a force of nearly 1,800 backcountry men along the North Carolina-South Carolina border. The American victory, known as the Battle of King's Mountain, forced Cornwallis to change his plan to remain in North Carolina for fear that in his absence the same backcountry men who had defeated Ferguson would slip in behind him and retake South Carolina. Therefore, Cornwallis reluctantly returned to South Carolina. King's Mountain saved North Carolina for the time being and bolstered Patriot morale throughout the 13 colonies.