17 Oct. 1891–25 June 1957

See Also: Robert Cherry (Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History), Mildred Cherry

Robert Gregg Cherry, post-World War II governor of North Carolina and speaker and long-time member of the North Carolina House of Representatives, was born at Catawba Junction, near York, S.C., to Chancellor Lafayette and Hattie Davis Cherry. His mother died when Cherry was one year old and his father, a farmer and Confederate veteran, six years later. Cherry was sent to Gastonia, just across the state line, to live with his maternal grandfather, pioneer Gastonian Isaac N. Davis, and his uncle, Henry M. Lineberger.

Cherry attended the public schools of Gastonia and then was graduated from Trinity College in 1912. He completed a law degree at Trinity College in 1914, winning the Judge Walter Clark prize as the highest ranking student in the graduating class. Returning to Gastonia, he established a law practice with Alfred Lee Bulwinkle, long-time friend and future congressman from the area.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Cherry delighted in organizing among men in the Gastonia area a machine gun troop of the First North Carolina Cavalry, which he trained and commanded during service overseas. He always took great pride in having developed a group of local men into a fighting cadre. His interest in the military continued after the war, and he maintained membership in the National Guard until 1924. Cherry returned from the service in April 1919 to find that his friends had nominated him for mayor of Gastonia. He entered the race, won it in May of that year, and was reelected in 1921.

In 1931, Willis Smith, in an effort to gain a network of supporters for his own bid for speaker of the North Carolina house, persuaded Cherry to run for the house from Gaston County. Cherry won the election and continued to win the races biennially through 1939. In 1941 and 1943 he switched to the state senate, where he continued to represent his Gaston County constituency. His service in the house of representatives led to his own election as speaker in 1937. His resolute handling of the house in that crucial year of significant legislation under Governor Clyde R. Hoey won him the title "The Iron Major," a reference also to his military career. Cherry dispatched important social legislation with ease and took a personal interest in the social welfare programs, serving on the state board of public welfare.

By the end of the 1930s, he was being mentioned as a likely candidate for governor. Fulfilling a youthful ambition, he won the office in 1944 on a platform stressing improved health care and education, without a burdensome increase in taxes.

Cherry became the first governor from Gaston County and served during the difficult period of postwar readjustment for the nation and the state. He found the state with a budget surplus, which he sought to spend wisely for capital improvements while making plans for retiring the bonded indebtedness. Probably his two greatest accomplishments were in the areas of health care and education. He worked especially to improve facilities for mental health, spending in four years almost $12 million in state and federal funds combined (in all the years previously, only about $11 million had been spent in North Carolina for mental health). He also promoted an increase of 83 percent in public schoolteacher salaries and simultaneously reduced the average pupil-teacher ratio in the schools. While he did not achieve the level of road construction for which he had hoped, he set the stage for the road-building program of his successor, Kerr Scott, by laying plans and obtaining the supplies for future highway construction.

Cherry did not achieve a state-wide liquor referendum or a department of police and public safety, goals he had noted in his inaugural address. He maintained a moderate political image for his state when he refused to join the Dixiecrat revolt from the Democratic party. His moderate image in race relations was enhanced by his commutation to life imprisonment of the death sentence of a black man convicted of raping a pregnant white woman.

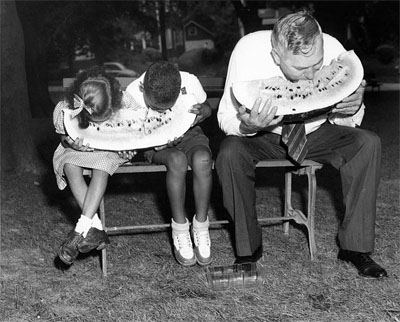

A man of keen wit, he reacted philosophically and humorously to public response to his controversial actions. He delighted in bringing a common touch to the governor's office. He preferred simple foods to the usual executive fare and usually walked to work, rather than riding in the executive limousine. He often surprised salespeople and state officials by doing his personal shopping and making his own telephone calls.

After he left the governor's office in 1949, Cherry returned to his law practice in Gastonia. There he lived with his wife, Mildred Stafford Cherry, daughter of a mayor of Greensboro, whom he had married in 1921. The Cherrys had no children.

Cherry died in 1957 after several weeks of hospitalization for toxic poisoning. He was buried in the Gaston Memorial Park. Under the terms of his will, his wife placed his personal papers in the North Carolina Department of Archives where they, along with his official gubernatorial papers, are available to researchers.