See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Tuscarora Territory

The tiny Algonquian tribes of the Albemarle were naturally the first to feel the effects of white settlements in North Carolina. As clapboard houses occupied old hunting grounds and cattle destroyed cornfields, the Chowanoc and Weapemeoc Indians gradually abandoned their lands. Some fled south, where they joined with the larger, more unified Tuscarora tribe. Others were bound into the colonial social structure as indentured servants or slaves. By 1700 scarcely 500 Indians remained in the Albemarle region.

For years, the Tuscaroras, an agricultural tribe related to the Iroquois, had inhabited the North Carolina Coastal Plain west of the Algonquians. According to one early eighteenth-century report, the Tuscaroras lived in fifteen different villages scattered throughout the Pamlico and Neuse River drainage basins. By the 1670s the Tuscaroras were aware that the Albemarle settlement was overspilling its bounds and the colonial government was extending its control southward. Immigrants by the hundreds invaded Tuscarora territory.

Tensions Rise Between Tuscaroras and Settlers

Although the circumstances leading up to the war were manifold, John Lawson put the situation quite plainly in his observation on relations with the Indians of the previous decade: "They are really better to us than we are to them; they always give us Victuals at their Quarters, and take care we are arm'd against Hunger and Thirst: We do not do so by them (generally speaking) but let them walk by our Doors Hungry, and do not often relieve them." Specifically, the outbreak of hostilities can be narrowed down to three Indian grievances: the practices of white traders, Indian enslavement, and, most important, land encroachment.

As more and more settlers flocked into the Pamlico region, misunderstandings increased between planters, who claimed perpetual and exclusive ownership of property, and Indian hunters, who expected continued access to the land. According to two Tuscarora Indians John Lawson encountered at the Eno River near present-day Durham, the English settlers "were very wicked People" who "threatened the Indians for Hunting near their Plantations." A settler writing after the Tuscarora War claimed that one of its main causes was colonists who "would not allow them to hunt near their plantations, and under that pretence took away from them their game, arms, and ammunition."

The settlement of New Bern in 1710 pushed the Indians to the point of desperation. Over 400 Swiss and German Palatines, led by Baron Christoph von Graffenried, displaced the Indian town of Chattoka at the junction of the Neuse and Trent rivers. Fearful of further colonial expansion, the Tuscaroras appealed to the Pennsylvania colony for asylum. In 1710, at a meeting with Pennsylvania commissioners and local Shawnee and Conestoga Indian leaders, Tuscarora emissaries proposed to relocate from North Carolina to the Susquehanna region. They sought a "lasting peace" with the Indians and government of Pennsylvania in order to "be secured against those fearful apprehensions they have these several years felt." The Pennsylvania commissioners, however, stipulated that the Tuscaroras present a certificate of good behavior from their North Carolina neighbors before they could "be assured of a favorable reception" in Pennsylvania. This demand effectively denied the Tuscarora request.

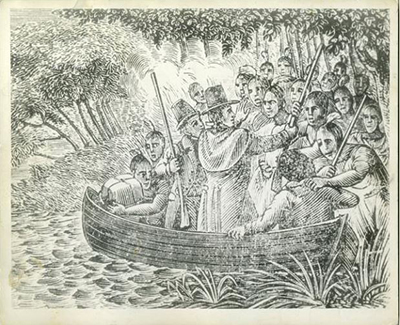

Unable to find refuge in Pennsylvania, the Tuscaroras took the offensive. In early September 1711 the Tuscaroras captured Baron von Graffenried, John Lawson, and two black slaves as they journeyed up the Neuse River. The Indians took their prisoners to the village of Catechna, about four miles north of present-day Grifton, in Pitt County. At Catechna, John Lawson quarreled heatedly with a Coree chief named Cor Tom. In response, the Indians tortured and killed Lawson. Graffenried was more diplomatic and lived to describe the experience in word and picture. Known for harboring black fugitives, the Tuscaroras spared the slaves. Lawson had been dead little more than a decade when William Byrd wrote, "they [the Indians] resented their wrongs a little too severely upon Mr. Lawson, who, under Colour of being Surveyor Gen'l, had encroacht too much upon their Territories, at which they were so enrag'd, that they . . . cut his throat from Ear to Ear, but at the same time releas'd the Baron de Graffenried, whom they had Seized for Company, because it appear'd plainly he had done them no Wrong."

West of the present-day town of Snow Hill in Greene County the Tuscaroras' determined struggle to retain their homeland was brought to an end. Here, on 20 March 1713, Moore's forces began their attack on Fort Neoheroka. For three days the Tuscaroras withstood the South Carolina Indian onslaught. Finally Moore's forces set fire to the bastions and to buildings within the Tuscarora stronghold. By mid-morning on 23 March they had routed the last of its Indian defenders.

The Tuscarora War was over. For the Tuscaroras the cost was bitter: 1,000 had been captured and enslaved; 1,400 were dead. A handful remained in rebellion until February 1715, when a treaty concluded the war. Most of the Tuscarora survivors migrated northward to become the sixth and smallest tribe of the powerful Iroquois League. In 1717 the few who remained in North Carolina received land on the Roanoke River near present-day Quitsna.