See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Towns Central to Rural Life

Out of a total population of less than 200,000 in 1770, there were fewer than 5,000 North Carolinians who lived in places that might be called urban. Though they were all quite small, towns served North Carolina society as centers for government and trade. Every county courthouse attracted a collection of storekeepers, tavernkeepers, and artisans to serve the rural citizens as they transacted legal business. Moreover, even the most self-reliant pioneer could not make his own salt or iron, and few free families felt they could do without sugar, coffee, tea, or similar imported products. These articles could come only from stores, and a conveniently located store soon attracted enough business to form the basis for a hamlet.

Settlers were unwilling to live in the backcountry without occasional purchases from the outside world. For the planter who planned his whole year's work with the expectation of selling staple crops, market towns were clearly central to every economic activity. Though few in number, North Carolina's townsmen were crucial to the rural way of life.

Commerce called the towns into existence, but the little settlements meant far more to the average country family than sites for buying and selling, or even for carrying our legal business in the courts. Elections were held in towns and so were meetings of the Assembly. Militia members gathered in towns to drill, and the congregations of the established church worshiped there. Taverns abounded in every town from the tiniest hamlet to the busiest seaport and ranged in quality from filthy dramshops to elegant hostelries for gentlemen.

Of all the eighteenth-century trading centers on North Carolina's inland rivers, Halifax is the best preserved today. J. F. D. Smyth visited the little port in the 1770s and described it very favorably. "Halifax is a pretty town on the south side of the Roanoke," Smyth told his readers. "About eight miles below the first falls, and near fifty miles higher up than the tide flows, but sloops, schooners, and flats, or lighters, of great burden, come up to this town against the stream, which is deep and gentle. Halifax enjoys a tolerable share of commerce in tobacco, pork, butter, flour, and some tar, turpentine, skins, furs, and cotton." Of the town's architecture, he declared, "There are many handsome buildings in Halifax and vicinity, but they are almost all constructed of timber, and painted white."

Too Much to Drink

Entertainment in the towns was a welcome relief from the monotony of rural life, and the typical visit to a town became the occasion for cutting loose from the restraints of ordinary existence. In a variety of ways, moreover, the pleasures that North Carolinians sought in towns were reflections of the same concerns, hopes, and fears that arose out of their work and their less dramatic daily lives. Consuming alcoholic beverages was a common practice and drunkenness often a problem in the new state. One visitor, William Attmore, recorded North Carolinians' drinking habits. "It is very much the custom in North Carolina," he wrote in his journal, "to drink Drams of some kind or other before Breakfast; sometimes Gin, Cherry bounce, Egg Nog, etc." On Christmas morning, he recalled, "according to North Carolina custom we had before Breakfast, a drink of egg nog." The Raleigh Register of 20 February 1818 reported a drunken incident that proved fatal: "Joseph Steele and Joshua Wody, on the 3d instant, were drowned in Haw River, from crossing John Thompson's Ford, one on horse, in a state of intoxication. Both have left wives and families to lament their premature end." The same issue of the Register noted that "the body of Barlett Dowdy, of Chatham county, was found in the Snow on the 6th instant, after lying six days. It is supposed he was in liquor, and [upon his] lying down, the Snow fell and covered him, and he rose no more!" The chance for a drink, a hand of cards, or even an eye-gouging fight was a source of excitement that few pioneers would pass up. The popularity of these entertainments probably said more about the character of North Carolina society than President Caldwell would have preferred to admit.

Death by Dishonor

The honor of a gentleman was his reputation for independence, reliability, and physical courage. The gentleman could not be commanded or insulted by others. He was always in control of his own actions and could therefore be relied on for rigid personal honesty and for meeting every contractual obligation. His power to command himself as well as others set him apart completely from those who allegedly lacked these attributes most: poor white people, enslaved Black people, and women, who were known as "the weaker sex." In a system based on personal credit, honor had clear economic value, and it also stood for the privileges of race, class, and sex. Vital to a gentleman's economic and social standing, it had to be defended at all costs. In a competitive society, others were always ready to advance their own positions by deliberately inpugning the honor of their rivals. Insults were therefore not uncommon, and the practice of dueling was the bloody result. A canny man, John Wright Stanly avoided the ultimate test of his reputation, but his heirs did not. Three of his five sons and at least one grandson participated in duels; two of those sons died, and the other killed his opponent.

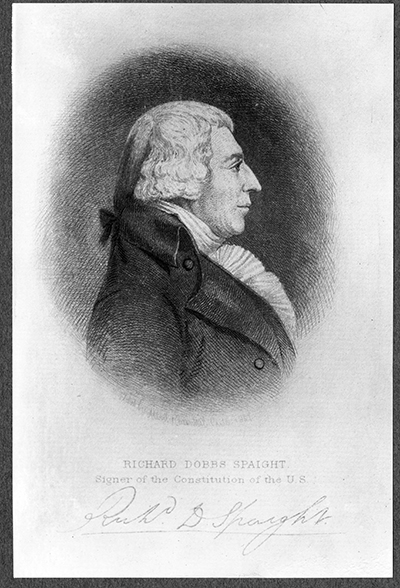

John Stanly won election to Congress in 1801 over a fellow New Bernian and former North Carolina governor, Richard Dobbs Spaight. Republicans like Spaight were often just as aristocratic in private life as Federalists like Stanly, but they won popular approval by branding Federalism as undemocratic and injurious to rural interests. In 1802 Spaight sought election to the state Senate, and Stanly worked against his election. By throwing doubt on Spaight's private adherence to Republican tenets, Stanly offended Spaight's honor as a gentleman, and Spaight instantly called for "that satisfaction which one gentleman has a right to demand from another." Although at first Stanly averted the duel by a timely explanation, an escalating exchange of insults and insinuating handbills finally led to Stanly's challenge to Spaight, and a duel was set for 5:30 p.m. on 5 September 1802, in the rear of the Masonic hall on the outskirts of New Bern. The outraged gentlemen would not let any piddling city ordinance against gunfire stop them; the weapons were pistols at ten paces. An eager crowd of onlookers turned out to gawk at the spectacle.

The demands of honor were technically satisfied by a single exchange of shots, but, when the first pair of balls missed their targets, Spaight and Stanly kept firing. On the fourth round, Spaight fell, wounded in the side, and died the next day. Stanly was then twenty-eight years old. Spaight was fifty-four, roughly the age of Stanly's deceased father. The young man took refuge from prosecution in Virginia, but, confident that the law would not preclude a gentleman's right to defend his honor, he asked for executive pardon from Governor Benjamin Williams. The request was promptly granted, and Stanly continued his distinguished career without further interruption.