The Stanly–Spaight Duel was the most notorious affair of honor in North Carolina history. On the evening of September 5, 1802, John Stanly mortally wounded Richard Dobbs Spaight behind New Bern’s Masonic hall with a pistol shot to the side. The confrontation marked the culmination of an intense political rivalry that had been building for more than two years and exemplified the southern culture of honor, which compelled elite men to attach life-or-death importance to their reputations.

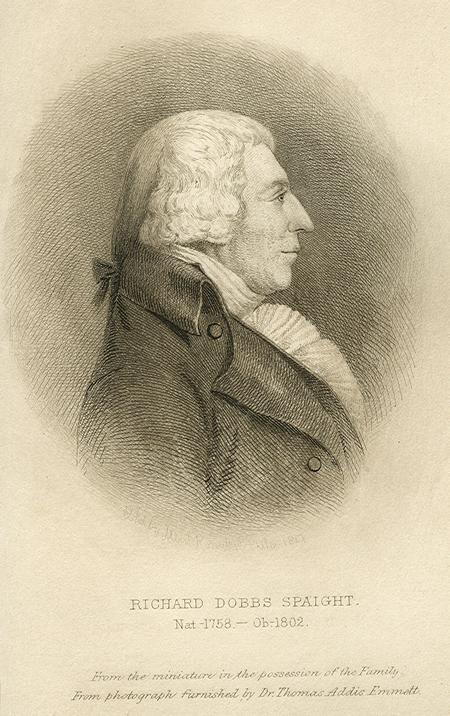

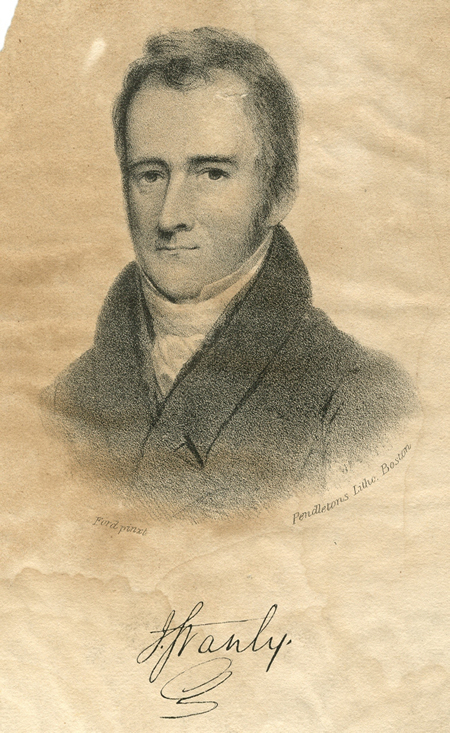

Richard Dobbs Spaight, born in 1758 in New Bern, was a prominent, respected public figure at the time of his death. Grandnephew of Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs, Spaight served under General Richard Caswell during the American Revolution. Afterward, he was elected to the General Assembly and later represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress and at the Constitutional Convention, where he became one of three North Carolinians to sign that document. From 1792 to 1795 Spaight served as North Carolina’s first native-born governor, and from 1798 to 1801 he represented the state’s tenth district in Congress, switching from the Federalist to the Democratic-Republican Party during his second term. Running for a third term in 1800, his opponent, twenty-six-year-old Federalist John Stanly, began a series of rumors about Spaight’s allegiance to his new party. In a public handbill circulated in August of that year, Stanly (1800) stated that Spaight “pursues the crooked policy of being occasionally on both sides.” Stanly won the election.

Two years after his Congressional defeat, Spaight sought election to the North Carolina State Senate. On Sunday, August 8, 1802, in the midst of Spaight’s campaign, John Stanly renewed his verbal assault. Stanly, a noted lawyer and orator, and orphan son of a prominent local merchant, voiced his opinions on a crowded New Bern street corner. According to one witness, Stanly stated that although Richard Dobbs Spaight “‘was a republican…Federalists could always command his vote; or when they were hard run could always get Mr. Spaight’s vote’” (Spaight 1802b). Hearing that Stanly had accused him of political flip-flopping, an angry Spaight quickly drafted a letter, which he sent to Stanly via his friend, Dr. Edward Pasteur. He declared that Stanly’s assertions were “an absolute falsehood, I consider as a direct attack on my Character, and one that I will not suffer any man to make with impunity.” Spaight (1802b) went on to demand a ritual confrontation, asking for “that Satisfaction which one Gentleman has a right to demand from another.” Stanly sent a letter back by his friend, Edward Graham, asking Spaight to consider “that you are a candidate while I am a voter, [and] that the political opinions of the candidates are fair subject of discussion, I presume you will acknowledge my right also to converse on that subject” (Stanly, 1802a). The men exchanged letters twice more that day and by nightfall had agreed to let the matter rest—though Spaight desired to publish the entirety of their correspondence because “what ha[d] been said may have made an improper impression on the public mind” (Spaight 1802a).

Stanly left the next day to attend court in Jones County. When he returned the following week, he read Spaight’s account in the New Bern Gazette and concluded that the article portrayed him as having made “humiliating concessions” (Stanly 1802b). Stanly wrote back to the Gazette with his own version of events, which Spaight again countered. After yet another exchange, Stanly printed a handbill on September 4, which he circulated throughout the town. In it, he (n.d.) accused Spaight of having a “spirit, malicious, low & unmanly.”

Spaight again answered, this time with his own handbill, stating that “Mr. Stanly is both a liar & Scoundrel…I shall allways [sic] hold myself in readiness to give him satisfaction_ [sic] & to assure him that if he ask for it once he shall not be under the necessity of doing it a second time” (Stanly n.d.-a) After the publication of these words, Stanly sent a letter to Spaight requesting that they meet to duel “as soon as may be convenient” (Stanly 1802b).

Settling seemingly minor disputes through ritualized murder seems bizarre—if not repulsive—to modern sensibilities. In Stanly’s and Spaight’s world, however, dueling made sense. In the antebellum South, a white man’s personal honor was his most cherished possession. Enslaved African Americans were clearly at the bottom of the southern social order and were thought of by whites as having no personal honor. All white men could claim a certain degree of honor by virtue of skin color and gender. However, those who owned land and slaves—and especially those who held public office, like Stanly and Spaight—relied most on their public reputations and had the most to lose if dishonored in the public mind. Men from this upper class, therefore, engaged most frequently in dueling (Wyatt-Brown 1982).

Being an honorable man meant having others accept your words and actions as true. Consequently, duels often resulted from the accusation of lying—an implication that another man was dishonest and, therefore, dishonorable. Though the Stanly–Spaight Duel came out of Stanly’s initial criticism of Spaight’s party allegiance, the central issue in the dispute was not his actual voting record—that could have been easily verified should the two parties have chosen to do so—but that Stanly accused Spaight of inconsistency and dishonesty. If a man of honor were to ignore accusations of lying, he would, in effect, legitimize them. A man who was publicly dishonored would lose his friends, business connections, and elected office. To be without honor was to be equated with the lowest possible station in life—slavery. Death was the preferable alternative (Greenberg 1990).

At 5:30 in the afternoon of September 5, 1802, Stanly, Spaight, and their seconds, Graham and Pasteur, met on the outskirts of town. In front of approximately three hundred spectators, they took aim and fired. The flintlock smoothbore pistols they used missed their marks. The men fired again. Spaight’s ball grazed Stanly’s shirt collar, but still the two men were unharmed. Townspeople begged the two opponents to call a truce. Spaight refused, and the third shots missed once more. On the fourth round of fire, Stanly’s ball struck Spaight in the side (White 1802; Watson 1987). The respected statesman crumpled to the ground. He died the next day.

In the end, the duel led not only to Spaight’s death but to Spaight’s influential friends bringing a murder charge against John Stanly. Stanly avoided prosecution by appealing to Governor Benjamin Williams, referencing “the dignified sense of Honor which adorns your own Character” and asking “whether it was possible, or would have been proper for me to acquiesce with humility to have bowed myself to the opprobrious epithets of ‘liar & scoundrel’” (Stanly n.d.-b). As a man of honor himself, the governor understood Stanly’s predicament and pardoned him. However, on November 5, 1802, the General Assembly (1802) passed an act “to Prevent the Vile Practice of Dueling within this state.” The death of a high-profile politician pushed many to consider the drawbacks of dueling, and the new law prohibited duel participants from holding public office and required them to pay a heavy fine. It also stated that the survivor of a duel to the death would be executed without benefit of clergy. Though as historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown writes (2007, 303), “it would be a mistake…to argue that duels were as much deplored as southern hand-wringing would lead an observer to believe.” Many prominent North Carolinians simply took their duels to Virginia or South Carolina in following years. Ultimately, since those politicians who passed anti-dueling laws were from the social class that most often engaged in dueling, such legislation was rarely enforced.

John Stanly lived until 1833, though he spent the final seven years of his life in debt and paralyzed from a massive stroke. He also lived to see two of his brothers—Richard and Thomas Stanly—die in duels. The honor culture that encouraged such displays of violence continued to gain importance among white southerners. Not until the massive social and cultural changes of the Civil War era did dueling truly die in the South.