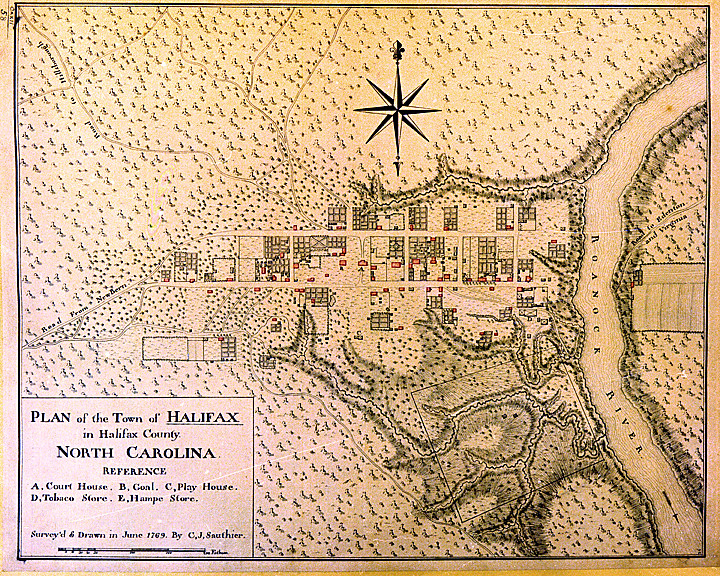

Between 1768 and 1771 Claude Joseph Sauthier, a French surveyor and cartographer, was commissioned by royal governor William Tryon to create a set of detailed maps for North Carolina's chief (principally political or commercial) colonial towns and one battlefield. The towns that Sauthier mapped, in order, were Hillsborough (October 1768), Brunswick Town (April 1769), Bath and New Bern (May 1769), Edenton and Halifax (June 1769), Wilmington (December 1769), Cross Creek (Fayetteville) and Salisbury (March 1770), and Beaufort (August 1770). In 1771 Sauthier also mapped the Alamance Battleground, the scene of the decisive battle of the Regulator uprising against Tryon's militia prior to the American Revolution.

Sauthier delineated key buildings or areas-such as churches, courthouses, markets, jails, mills, tanyards (or "tann yards"), flagstaffs, schools, breweries, still houses, and some residences-by an alphabetical letter in descending order of importance, with churches usually listed as A, courthouses as B, jails as C, and so on. Major roads leading to neighboring or important distant towns were carefully marked. Geographic features such as rivers, creeks, mountains or marshes, dams, canals, and even racetracks were usually identified.

Buildings were indicated by small rectangles with heavy outlines on two sides-usually the right angle and the lower side. These two heavy lines have been interpreted as indicating a shadow cast by the bulk of the building, a convention used by Sauthier to illustrate mass. The idealized "formal gardens" behind many town residences also reveal this convention, suggesting a mass of green foliage rising above the surrounding paths. The homes shown on the maps were all built near the street and were typically rectangular in shape, with fields or gardens located adjacent or behind the structures. The X inscribed within the perimeter of a structure has been interpreted to mean that it was a single-story building. On the originals some buildings were shown in color highlight (red), which may indicate dwellings.

Sauthier's maps have offered valuable two-dimensional guidance into town plans and features of eighteenth-century North Carolina. His map of New Bern was used by architectural restorationists in the reconstruction of Tryon Palace. For decades archaeologists have consulted his maps of Halifax, Brunswick Town, Hillsborough, Edenton, and Bath to investigate subsurface ruins of the old towns. Historians have also used these maps to re-create historic towns and battlefield layouts for public visitation and education.

As research tools, Sauthier's maps have provided archaeologists, architects, historians, and cartographers with colonial period templates of urban lot arrangements, which are often camouflaged by later nineteenth- and twentieth-century alterations. Thus, they offer a glimpse into what otherwise would never be visible in its entirety-the towns and battlefields as they once were. The originals of most of these maps became the property of the British Museum in London.