By the start of the nineteenth century, 40 private academies existed in the state, including Salem Female Academy (founded in 1772). All of these schools catered primarily to wealthy white students-no private schools accepted black children, free or enslaved, and few poor white families could spare the time or expense to send children to private schools. It was not until the nineteenth century that religious organizations such as the Society of Friends (Quakers) began to offer black children any formal education.

In the first six decades of the new century, 287 academies were chartered by the General Assembly. A few flourished, but many closed after a short time. When the legislature did not respond quickly enough in establishing an institution to more conveniently serve the western counties, the Presbyterian Church took the initiative, founding Davidson College in 1837. Other churches soon followed its lead. In Wake County, Baptists opened the Wake Forest Manual Labor Institute (modern Wake Forest University) in 1834, and in Randolph County, Quakers and Methodists organized Union Institute (later Trinity College and eventually Duke University). In 1851 the German Reformed Church founded Catawba College in Newton. These institutions trained men as ministers for the growing congregations across the South.

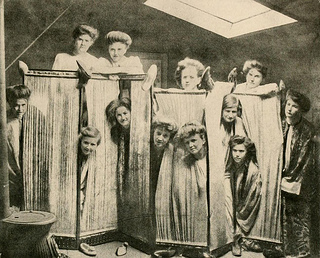

Female education progressed much more slowly: it was not deemed necessary to train young women in anything but the domestic arts, with a little French, music, dancing, and drawing sometimes added. Before there were female academies in the state, classes for girls were sometimes provided in the boys' schools by women teachers. Salem Female Academy, the state's oldest girls' school, was still open in 2006, having never moved from its original site. At first a "day-school," Salem became a boarding school in 1802. Salem College was developed later, but the academy has retained its identity as a female preparatory school.

The Public School Law of 1839 initiated a gradual shift of primary education to public jurisdiction, although many private schools continued to flourish. Some children of poorer families began to enjoy the same educational opportunities as their wealthier neighbors. Virtually all educational institutions in the state suffered during and immediately following the Civil War. Endowments vanished, buildings and resources were damaged or destroyed, and for a brief period even the University of North Carolina was closed. Soon after the war, however, newly emancipated blacks and progressive whites led the charge for universal, state-supported public education, while wealthy families continued to send their children to private alternatives. Several black schools were established by Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Episcopal, Methodist, and Baptist churches in the postwar era. Raleigh Institute (modern Shaw University), opened in 1865 as the South's first black institution of higher learning. Other important church-supported black schools dating from this era include Biddle Memorial Institute (modern Johnson C. Smith University) in Charlotte (1867), Saint Augustine's Normal School and Collegiate Institute (modern Saint Augustine's University) in Raleigh (1867), Bennett Seminary (modern Bennett College) in Greensboro (1873), and Zion Wesley Institute (modern Livingstone College) in Salisbury (1879).

Private academies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century took many different forms. Many were modeled on the New England ideal-a secluded, exclusive institution providing intensive training in classics, religion, and other traditional subjects. (Several of these schools, including the Asheville School [1900] and Ravenscroft in Raleigh [1937], remain open today.) Other schools, such as Oak Ridge Military Academy (1853), emphasized military discipline and regimentation. Although the vast majority of private schools served white children, black parents also sought the perceived advantages of private education and, often with the aid of northern missionary societies, established private black institutions.