Part i: Diverse Currency and Severe Money Shortages in Colonial North Carolina; Part ii: Revolution-Era Currency and the Importance of North Carolina Gold Production; Part iii: The Civil War and the Nationalization of the Monetary System

During the American Revolution, monetary instability proved to be as much of a threat to the American cause as British muskets. In North Carolina, the provisional government had an empty treasury and no credit. Money was still needed to govern and equip troops, so North Carolina officials resorted once again to printing currency. In Philadelphia, to help finance America's war effort, the Continental Congress authorized the printing of Continental currency in dollars. Between 1775 and 1779, North Carolina and the other colonies were flooded with over $241 million in this money. Since little or no hard money supported this currency, it depreciated until it became virtually worthless.

The American dollar took its name from the large Spanish coin known to British colonists as the Spanish milled dollar, which was similar in size to the German Joachimsthaler, or thaler. The German thaler was eventually Anglicized into dollar. Small value Continental bills were in fractions of dollars. The current system of using 100 cents to equal 1 dollar was introduced in 1792 at the urging of Thomas Jefferson.

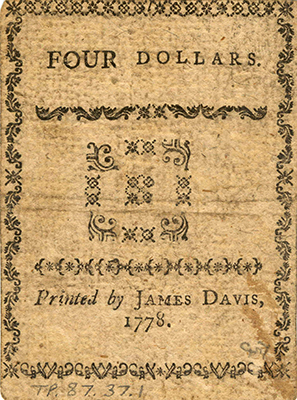

Most of North Carolina's revolutionary currencies were printed by James Davis, the colony's first printer, in New Bern and Hugh Walker in Wilmington. During the Revolution, Davis was entirely responsible for North Carolina's 1778 and 1780 money issues. His colleague, Walker, produced the intervening 1779 currency.

The values of North Carolina's wartime currencies had nearly collapsed by 1780, and after the Revolution all of the Continental currency and other moneys issued during the conflict were discredited. Since sizable deposits of gold or silver had not yet been found in the United States, and the supply of coins minted by the new national government remained insufficient, North Carolina found it necessary to print its own currency in 1783 and again in 1785. To distinguish these issues from the worthless Continental dollars, this new money carried values in British denominations: pounds, shillings, and pence.

When North Carolina joined the Union in 1789, the state government was forbidden by the U.S. Constitution to print money or mint coins. Although the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia began operation in 1792, it was many years before it and subsequent branches could strike and circulate enough coins to satisfy the needs of the states. Foreign coins remained legal tender until 1857. The central government did not specifically forbid the production of money in the private sector by individuals or businesses; as a result, until the Civil War most of North Carolina's paper money was issued by private commercial banks.

Gold from North Carolina mines began to add to the supply of coinage in the 1830s. German jewelers Christopher and Augustus Bechtler operated a private mint in Rutherford County from 1831 to about 1849, using gold from nearby mines. North Carolina gold also served the federal government. Prior to 1829, the state furnished all of the native gold coined in Philadelphia at the U.S. Mint. A branch of the federal mint was established in Charlotte in 1837, and it produced gold coins for the federal government until the Civil War, when it was seized by Confederate forces. Combined, the public operation in Charlotte and the Bechtlers' private mint produced almost $9 million in coinage before 1861.