16 Sept. 1834-17 Mar. 1912

1834-1870: Early Life

Alfred Moore Waddell was a lawyer, newspaper editor, Congressman, author, public speaker, Confederate soldier, and the self-proclaimed leader of the 1898 Wilmington Coup. He was born in Hillsborough, the son of Hugh and Susan Moore Waddell. He was the great-grandson of three of the state's Revolutionary leaders, Hugh Waddell, Francis Nash, and Alfred Moore, and thus came from a wealthy and prominent family from the Lower Cape Fear region. He attended Bingham's School and Caldwell Institute in Hillsborough, and graduated from The University of North Carolina in 1853. Waddell was admitted to the Bar Association in 1855.

By 1856, Waddell was living in Wilmington and practicing law. He became involved in politics and public speaking at this time. He backed the presidential ticket of the American party and spoke at a party demonstration in Wilmington. On March 5, 1857, Waddell married Julia Savage. They had two children, Elizabeth Savage and Alfred M., Jr. Waddell was appointed to his first public office in 1857 when he was named Clerk and Master in Equity for New Hanover County (1858–61).

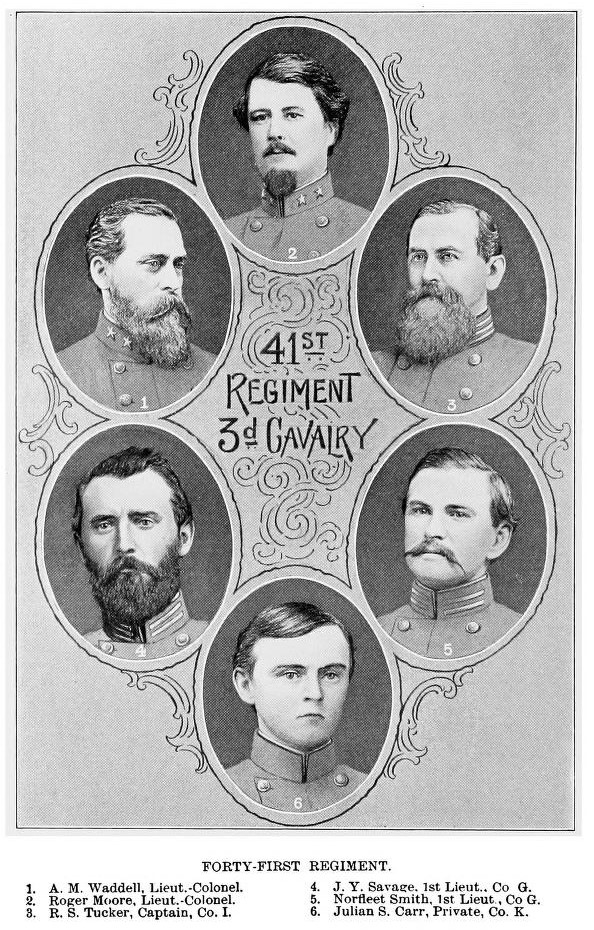

The 1860 census shows Waddell, along with his wife and children, living in the home of his father-in-law, T. Savage. His profession is listed as lawyer. He supported the Constitutional Union party, and attended the party's convention in 1860 as an alternate delegate from North Carolina. At this time, Waddell opposed secession in line with the party stance. He purchased and edited a Unionist newspaper, the Wilmington Herald, from 1860–61. Waddell’s views on secession changed after traveling to Charleston Harbor during the opening battle of the Civil War at Fort Sumter. He resigned as Clerk and Master in Equity and joined the Confederate army as adjutant of the NC fourth regiment of Infantry. Waddell rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Forty-First Regiment, Third Cavalry, of the North Carolina Volunteers before he was forced to leave the Army in 1864 due to ill health.

After the Civil War, Waddell returned to Wilmington and reopened his law practice, advertising “a connection with a distinguished law firm in Washington City, who have had years of experience in prosecution of claims of all kinds against the government….” Waddell also resumed his status as a public speaker in Wilmington. In July of 1865, Waddell spoke to the Black citizens of Wilmington about their standing in the community. His statement about voting rights for Black citizens was that he believed in “a standard of qualification for voters of some kind, either in intelligence or property, or both, and to allow every man who can attain that standard to vote, whether he be white, black, green, yellow, red, or any other color, and to prohibit any from voting who cannot attain that standard.” In 1866, Waddell and his father, Hugh, opened a Wilmington law office together.

1870-1879: Congressman

Census records for 1870 reveal that, by this time, Waddell and his family were no longer living with his father-in-law and the listed real estate value of their property was $12,000. Waddell accepted the nomination of the Conservative party to run for Congress in 1870. He was elected to the Forty-second Congress. Waddell was not immediately sworn in, as some sitting members of Congress argued he was ineligible. Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits anyone from holding office who took an oath to uphold the Constitution and then engaged in insurrection against the government. Republican congressman William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania, a friend of Waddell’s father, argued that Waddell was not under a “political disability” because his previous court appointment was clerical in nature. In 1871, Waddell took an oath of allegiance to the United States and was sworn into Congress. This oath was required of anyone seeking public office who had joined the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Waddell regarded the Enforcement Act, also called the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, as unnecessary and spoke out against it in his first Congressional term. The Act allowed the president to impose martial law and heavy penalties, and use military force to suppress the Ku Klux Klan. However, he voted in favor of establishing an investigatorial committee to look into “Southern outrages,” such as Ku Klux Klan activity and other actions designed to deprive southern Black citizens of their rights. Waddell was appointed as a member of the investigatorial committee. He signed the February 19, 1872 minority report which stated “had there been no wanton oppression in the South, there would have been no Ku-Kluxism.”

Waddell was re-elected to the three successive Congresses and served through 1879. During his second term, he was appointed to the Committee on Printing. In his third term, Waddell was appointed as the sole member of the Committee of Enrolled Bills, to the Joint Committee on the Library, to the House committee on post offices and post roads, and to a select committee to investigate elections in New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Jersey City. During his third term, Waddell was also awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree by the University of North Carolina in 1876.

During his four terms in the House of Representatives, “Waddell missed 492 of 1,696 roll call votes, which is 29.0%.” The Congressional record shows Waddell requested a leave of absence several times in his third term due to his wife, Julia, being ill, and later for her death in June 1876. In 1877, during his fifth and final Congressional term, Waddell was made Chairman of the Committee of post office and post roads. During his time as chairman, Waddell worked to improve postal service by creating more postal routes, increasing pay for postal carriers, and establishing a postal savings bank. Following Julia’s death, he married her sister, Ellen Savage, on July 1, 1878.

During his four terms in the House of Representatives, “Waddell missed 492 of 1,696 roll call votes, which is 29.0%.” The Congressional record shows Waddell requested a leave of absence several times in his third term due to his wife, Julia, being ill, and later for her death in June 1876. In 1877, during his fifth and final Congressional term, Waddell was made Chairman of the Committee of post office and post roads. During his time as chairman, Waddell worked to improve postal service by creating more postal routes, increasing pay for postal carriers, and establishing a postal savings bank. Following Julia’s death, he married her sister, Ellen Savage, on July 1, 1878.

Newspaper articles published about Waddell often expressed admiration for him, stating “he gained for himself by his eloquence a reputation second to none” and that his lectures “held the great audience in close attention.” Accounts from Republican papers differed, and The National Republican of Washington, D.C. referred to Waddell as “an incendiary.” This article also foreshadowed Waddell’s involvement in the Wilmington Coup by exploring his desire for a “race war,” for control over the election process, and his involvement with violent White Leagues. Another Republican newspaper, Wilmington’s Weekly Post, was also critical of Waddell. In March 1876, the paper published an article accusing Waddell of “being a common gambler and a frequenter of low and disreputable places.” Waddell retaliated against the editor of the paper by hitting him with a cane. Waddell was indicted by a grand jury for his action and The North Carolina Superior Court fined him ten dollars. In an 1876 article, The National Republican indicated that Democratic support of Waddell was waning, though he was later re-elected. The Weekly Post alleged that Waddell was re-elected by means of “fraud, intimidation, and corruption.”

1880-1898: Public speaking and writing

Waddell spent months traveling to deliver campaign speeches during election years. He also spoke at many events unrelated to politics throughout his life. He delivered commencement addresses at Wake Forest University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson College, Davidson College, Virginia Medical College, and Trinity College. He was often a speaker at Masonic events, Confederate and Union veteran meetings, and Teacher’s Assembly meetings.

Democratic overconfidence and the rise of the Fusionist party led to Waddell’s defeat by Daniel L. Russell in 1878. The 1880 census originally listed Waddell’s profession as “State Congressman.” This was later revised to "Lawyer," as Waddell was not serving as a State Congressman after 1879. He is listed as living with his wife and two children in Wilmington.

Though no longer an officeholder, Waddell remained politically active. He took part in campaigning for presidential candidate Winfield Hancock in 1880, and spoke in Vermont, New York, and Maine. He continued his strong affiliation with the Democratic party, serving as a delegate to the national conventions of 1880 and 1896, and as elector-at-large in 1888.

Waddell began writing during this time and started by authoring several newspaper articles about his experiences campaigning in New England. The articles followed the travels of the “rebel brigadier” and often included commentary on the political climate and Northern views of the South.

Waddell moved to Charlotte in 1882 to become editor of the Charlotte Journal-Observer. A year later, Waddell retired from the editorship and canvassed across the state for the Democratic party. While living in Charlotte, Waddell announced himself as a candidate for Congressional office in the Sixth District. Ultimately, he was not selected by the Sixth District Democratic Convention, and after this political defeat, Waddell returned to Wilmington and opened a law practice.

In July 1885, Waddell published an article in the Western Sentinel expressing his disappointment that North Carolina “has absolutely no visible evidence in the form of a monument or statue, or painting, or other memorial - erected by the State - that she ever produced a man worthy of remembrance.” Two years after his article about a lack of memorials in the state, Waddell was invited to be the speaker at the unveiling of a Confederate monument in Smithfield.

Waddell became more involved with the church at this time and was elected to the Episcopal Diocesan Convention in 1890. He also wrote and published his first book, A Colonial Officer and His Times, 1754–1773: A Biographical Sketch of General Hugh Waddell of North Carolina (1890), which was about his grandfather, Hugh Waddell. In 1894, Waddell was appointed as the solicitor of the criminal court of New Hanover County.

At the unveiling of a Confederate monument at the Capitol in Raleigh on May 20, 1895, Waddell spoke and gave “a masterly defence [sic] of the cause for which [the Confederate soldiers] fought.” In June, he gave the commencement address at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The University also conferred an honorary Doctor of Laws degree to him. Waddell’s second wife, Ellen, died in October 1895.

At this time, Waddell became critical of organized religion. In 1896, the newspapers published a letter by Waddell regarding eternal punishment. In the letter, he stated his conviction “that the result of the teaching of endless suffering has been altogether harmful to the interests of true religion, in that it has driven multitudes of men and women into atheism and skepticism, when it is doubtful if it ever induced one human being to sincerely embrace Christianity.” At the age of 62, Waddell married a third and final time. He married 33-year-old Gabrielle de Rosset on November 10, 1896.

1898: Wilmington Coup

A volatile political environment preceded the events of the Wilmington Coup. Early in 1898, the Chairman of the National Democratic committee suggested joining with the Populist party. Waddell wrote a letter to the Chairman denouncing the idea because he felt that the price of such a merger would be too high. He stated that in North Carolina the “fight…is between barbarism and civilization – between white men and negros, manipulated by unprincipled demagogues” and he would rather lose the election than win through “dishonorable methods.”

As the election of 1898 approached, Waddell addressed the citizens of Wilmington in October “on the rightfulness and expediency of maintaining the absolute supremacy of the white people.” He denounced the state of political affairs in North Carolina. He asserted a state of political crisis and demanded change. He claimed this change would come even if it meant “chok[ing] the current of the Cape Fear with carcasses.” This speech was given late in the election cycle, but it was tied to the statewide Democratic campaign focused on white supremacy. The 1898 Democratic campaign, combined with voter intimidation, physical threats, and election tampering from the Red Shirts, ensured Democratic wins throughout the state. This included New Hanover County.

After the election, Democrats in Wilmington called a meeting to be held on November 9, 1898. Waddell was not involved with planning, but attended the public meeting. He was elected chairman early in the event and read a set of resolutions titled the “Wilmington Declaration of Independence.” This document made specific demands of Wilmington’s Black community. It included the removal of The Daily Record newspaper and its editor, Alex Manly, who had published an article in August 1898 destigmatizing interracial relationships.

Waddell, acting as chairman, appointed a committee of twenty-five men to carry out the actions included in the resolutions. Wealthy and prominent members of Wilmington’s Black community, referred to as the Committee of Colored Citizens, were summoned for a meeting with Waddell and his new committee. Waddell conducted the meeting and “presented the resolutions as the ultimatum …firmly explained the purpose of the meeting … and [announced] that no discussion would be allowed.” Waddell ignored or reprimanded any of the Black men who dissented. He also declared that a written response to the demands was expected by 7:30 a.m. on November 10th.

The Committee of Colored Citizens met and composed a reply written by Armond W. Scott, a young lawyer who agreed to deliver the letter. As Scott headed to Waddell’s house, he encountered Red Shirts and other armed white sentinels. Fearing for his safety, Scott delivered the letter to the post office. On the morning of November 10th, Waddell left his home around eight o’clock and walked to the armory of the Wilmington Light Infantry. A mob of over 500 armed white men waited at this location to hear how the Black citizens had responded. Waddell knew what the Committee of Colored Citizens had written and that the letter had been mailed, but upon his arrival he told the gathered crowd that he had not received a response.

The crowd began calling for Roger Moore, another Democratic leader in Wilmington, to lead them in an attack on the Record printing press. Waddell sent messages to Moore’s home and office, despite knowing Moore was at a command post not far from the armory. Waddell announced to the gathered men that Moore could not be located and the group quickly turned to Waddell to lead them. He called for seventy-five men to join him in marching to the press and began arranging men in a military-like column. The entire group joined the procession and walked the seven blocks to the printing press. Manly had fled Wilmington, but this did not prevent the mob from burning down the newspaper office. Waddell’s account of events states that after the printing press had been destroyed he instructed the crowd to “go quietly to our homes, … obey the law, unless we are forced, in self-defense, to do otherwise.” The congregation on November 9th and the destruction of the press on November 10th were the beginnings of the violent Wilmington Coup.

As the violence of the Coup escalated, Waddell called for a meeting of the Committee of Twenty-Five in the mid-afternoon of November 10th. Resignations of the current Fusionist mayor and police chief were demanded at the meeting. The mayor and police chief resisted, but eventually resigned out of fear for their own safety. “Waddell and his committeemen… began selecting their own mayor, police chief, and aldermen…. Eight white supremacists were selected as aldermen, seven of them from the Committee of Twenty-Five … and two who had directed the rioters.” Waddell was chosen to be mayor. Members of the Committee armed themselves and marched to city hall to finish ousting the current government officials. One newspaper recounted that “the Fusionist officials in power… ‘resigned,’ and the new revolutionary government, consisting of A. M. Waddell; Mayor, E.G. Parmalee, Chief of Police, and a Town Council made of prominent businessmen assumed control.” The new government’s first order of business was to swear in 250 “special policemen.”

The ongoing violence of the Coup tested Waddell’s leadership as he worked to minimize violence in the city. When Red Shirts conspirators came to the Wilmington jail intending to lynch six prominent Black men incarcerated there, Waddell and other local Democratic leaders stood guard to prevent the killings. On November 11th, Waddell issued a proclamation from his guard post at the jail. In this proclamation, Waddell stated he would “preserve order and peace….and the law [would] be rigidly enforced and impartially administered to black and white people alike.” Later that day, the jailed Black citizens were given a military escort to the train station and banished from the city.

On November 12th, the newspapers published another notice issued by now-Mayor Waddell affirming to citizens, Black and white, that they would be “protected” and warning them of creating any further conflict. Waddell made efforts on November 13th to assure Black citizens hiding in the woods that they were safe to return to the city. Waddell’s intent to restore peace was clear when he fined several men for disorderly conduct on November 14th. He also informed Colonel Walker Taylor that the services of the military were no longer needed. Waddell received letters of congratulations and a gift of a gold and ivory gavel by former Wilmington residents for his successful role in the Coup. Waddell’s involvement in the coup is undeniable; however, his role as a leader, particularly in the planning stages, was later refuted in a letter written by Roger Moore’s wife, Susan.

1898-1912: Mayor Waddell and death

After the coup, Waddell was re-elected to a two-year term as mayor in April 1899. That year, Waddell spoke at a Conference in Alabama devoted to discussing the “race problem,” or the rights of Black people in the South. In his speech, he described the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave Black citizens the right to vote, as the “greatest political crime” and concluded that it should be repealed or modified. Waddell served as mayor until he lost the election in 1903 and resumed the practice of law. He was re-elected as Mayor in 1905. Waddell made several other runs for political office during this period, but was defeated each time. Waddell published two more books: an autobiography titled Some Memories of My Life (1908), and a compiled history titled A History of New Hanover County and the Lower Cape Fear Region, 1723–1800 (1909).

Waddell died suddenly on March 17, 1912. Newspapers reported that he suffered an “attack of angina pectoris,” or a heart attack. His funeral was held at Saint James’ Episcopal Church in Wilmington. He is buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington.