24 May 1827–9 Aug. 1885

Washington Caruthers Kerr, geologist, was born in eastern Guilford County in the Alamance Creek–Alamance Church region. His Scot-Irish parents were William M. Kerr, a small farmer, and Euphence B. Doak, who reportedly possessed unusual mechanical talent. When "W. C." was a small child, the family moved to the Haw River area in western Orange County, which in 1849 became the eastern section of the new county of Alamance. His father died about 1835 and his mother in 1840, leaving four sons and two daughters. W. C., quick and bright, was the namesake of the family's pastor, the Reverend Eli Washington Caruthers. Indeed, Caruthers was then the state's outstanding Presbyterian as well as principal of a good preparatory school in Guilford County. Cared for and guided by his mentor, young Kerr entered the sophomore class at The University of North Carolina and was graduated in 1850 with highest honors. He taught for one year at Williamston in Martin County, and for another year at Marshall University in northeastern Texas.

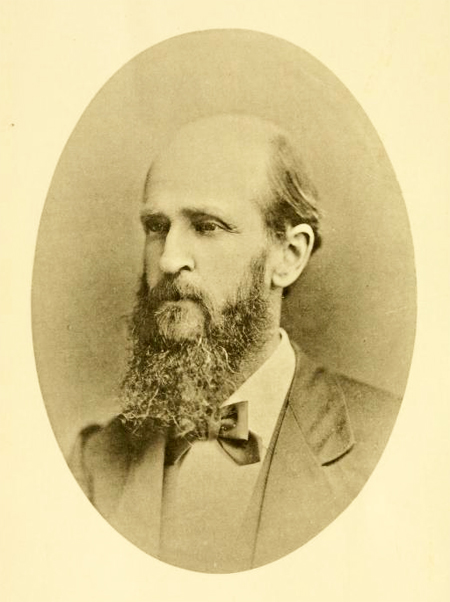

In 1852 Kerr was appointed as a computer in the office of the Nautical Almanac at Cambridge, Mass., and held the post for almost five years. He also studied at the Lawrence Scientific School and came in contact at Harvard University with such luminaries as Louis Agassiz, naturalist, and Asa Gray, botanist. Between 1857 and 1862 he served as professor of chemistry, mineralogy, and geology at Davidson College, teaching upper-level courses. One of his students recalled in later years: "We used to call him 'Steam Engine,' instead of Kerr, such was his promptness to time and rapid motion." Another remembered: "He was a man of small physical stature,—with massive forehead whose amplitude was increased by baldness and his way of wearing his hair. His face was thin and intellectual—his eyes blue and piercing . . . his voice . . . clear and penetrating. He . . . could not brook shamming or laziness. His rebukes were often cutting—always deserved." Kerr's contribution to the Confederacy (1862–64) was as chemist and superintendent of the Mecklenburg Salt Company at Mount Pleasant, S.C., near Charleston; he improved the manufacturing process and cut the cost of firewood by half.

Governor Zebulon B. Vance appointed Kerr state geologist in 1864, but conditions in North Carolina during the final year of the Civil War precluded either systematic work or a salary. In 1866 he was reappointed by Governor Jonathan Worth. Kerr evaluated in Raleigh the "geological reconnaissance" performed by Chapel Hill professors Denison Olmsted and Elisha Mitchell in the 1820s (the first state survey in the nation), and the more detailed survey of state geologist Ebenezer Emmons during the 1850s. Neither, however, covered adequately the western quarter of the state, where most of the mineral resources were located. With an eye on economic development, Kerr concluded that the region beyond the Catawba River merited particular attention, and that an accurate geographic and topographical map of North Carolina should be produced.

Although not a trained specialist, Kerr was a keen observer and hard worker. His first official report stated that he had traveled, "mainly in the saddle," 1,700 miles in less than four months; his second, 4,000 miles in eleven months. The legislature appropriated only $5,000 annually for all geologic operations, which meant that Kerr could have no permanent assistants. Nevertheless, by 1870 his own statewide survey was ready for publication. The lawmakers, however, placed so low a priority on the work that it did not appear until 1875—a major frustration. Kerr's 325-page Report of the Geological Survey of North Carolina concentrated on topography, climate, geology, soils, fertilizers, and ores. His large fold-out geologic map was tinted in five colors by Mrs. Cornelia Phillips Spencer of Chapel Hill. The base for this map was that of the federal Coast Survey. After fifteen years of intermittent labor, Kerr in 1882 had calculated his own base, thus providing by far the most accurate map of North Carolina up to that time.

As state geologist he touched every county and, when not in the saddle, employed buggy, spring wagon, boat, handcar, or train. Always he collected specimens for the state museum in Raleigh. His correspondence was voluminous, his conferences frequent, his popular talks and articles many. He was a leading member of the state Board of Agriculture, lectured regularly on geology and related sciences at The University of North Carolina, and prepared displays of the state's resources for expositions both at home and abroad. A respectable number of his professional papers were read before, and published by, several scientific societies.

Kerr made two important theoretical contributions to geologic science. He was first in the United States to explain a phenomenon that many North Carolinians and South Carolinians had often noticed: along rivers flowing from west to east, their south banks presented bluffs and high ground, their north banks low plains and swamps. Citing Ferrel's "law of motion" (1859), Kerr deduced that this condition resulted from the coordinate action of stream flow and rotation of the earth. He was also first to describe the alternate freezing and thawing that produced "deep movement and bedded arrangement of loose materials on slopes," even very slight slopes—a "frost drift" analagous to "glacial drift." But his belief that glaciation occurred as far south as North Carolina was not accepted.

The satisfactions of his work were countered by certain vexations. Chief among them was the periodic meeting of the legislature and the inevitable confrontation between the state geologist, who favored plans for long-range economic development, and legislators, who expected immediate results for funds appropriated. To Kerr it was "real torture." Never robust, his health gradually deteriorated (from catarrah of the digestive organs) after age forty. Yet this period witnessed his greatest productivity. An associate declared that Kerr was "often impatient, often despondent" but "clung to his work, impelled and sustained by nervous energy alone."

In August 1882 he resigned his position to join the U.S. Geological Survey; some of his duties were in Appalachia, some in Washington. While in Washington, he prepared a report on the cotton production and general agriculture of North Carolina and Virginia for the Tenth Census, and wrote the article "North Carolina" for the ninth edition (1884) of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Finally his failing health persuaded him to give up regular work, resign from the Geological Survey, and spend summers in Asheville and winters in Tampa, Fla. The Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society at Chapel Hill elected him president in 1884, and the university honored him with the Ph.D. in 1879 and the LL.D. in 1885. During his lifetime Kerr was almost the only North Carolina-born scientist active in the state. His great service was to open the eyes of the people to their own natural resources, especially minerals. He died, of consumption, at Asheville and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh.

Kerr married Emma Hall of Iredell County in 1853. Their three children were William Hall, automatic-bagging inventor and manufacturer; Alice Spencer, a teacher who died of consumption at twenty-one; and Lizzie, who married Professor George F. Atkinson of Chapel Hill. In a letter to Lizzie from Burnsville dated 17 Nov. 1882, Professor Kerr, as most people called him, unconsciously left a portrait of himself: "I came in here Monday morning from Grandfather [Mountain], Tuesday went to Tom Wilsons, Wednesday to top of [Mount] Mitchell. Ground frozen hard & ice in path to top, & little lines of snow in the furrows of the rocks & whitening the top branches of the balsam trees. Day pleasant . . . I have taken board for party at Ray's, 4 men & 4 horses."