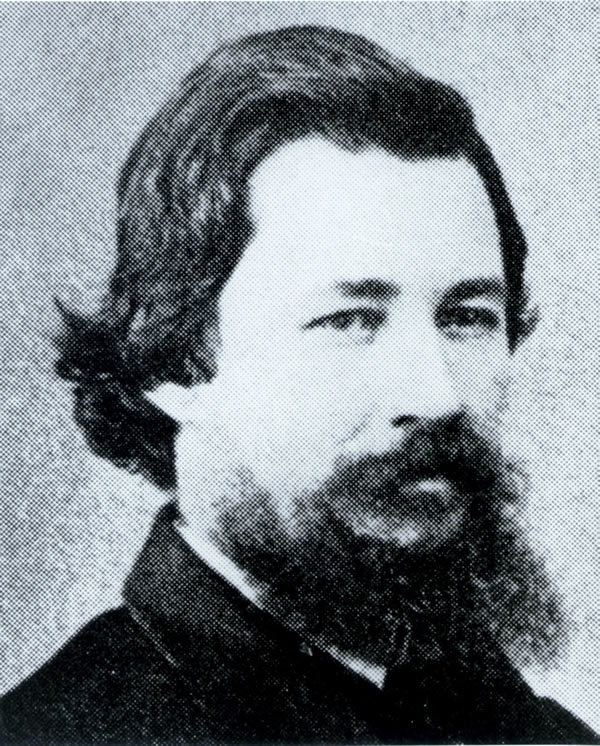

13 Feb. 1827–2 Sept. 1886

Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick, educator, chemist, and antislavery activist, was born in western Davidson County near Salisbury, the son of Elizabeth Sherwood and John Leonard Hedrick, a farmer and bricklayer of comfortable means. The family was descended from German immigrants who settled in the Piedmont section of North Carolina in the 1700s. After attending local schools, Hedrick received college preparation at Rankin's (or Lexington) Classical School, an academy directed by the Reverend Jesse Rankin near Lexington. In 1848 he entered The University of North Carolina as a sophomore; he distinguished himself particularly in mathematics, and upon his graduation in 1851 he was awarded "first honor in the senior class." President David L. Swain recommended Hedrick to former governor William A. Graham, secretary of the navy, for a clerkship in the office of the Nautical Almanac in Cambridge, Mass. Graham made the appointment, and while in Cambridge Hedrick also took advanced instruction at Harvard College under such prominent scientists as Eben N. Horsford, Benjamin Peirce, and Louis Agassiz.

Although offered a position at Davidson College as professor of mathematics in 1852, Hedrick declined it, deciding instead to return to his alma mater when the opportunity arose. In January 1854 the university appointed him to the chair of analytical and agricultural chemistry.

In Chapel Hill Hedrick acquired a certain notoriety because of his antislavery views in the antebellum South, although initially he had made no attempt to disseminate his opinions on the issue. But in August 1856 he was asked at the polls whether he would vote for the Republican presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, in the national election. Hedrick replied that he would do so if a Republican ticket was formed in North Carolina. The next month a short article entitled "Fremont in the South" appeared in the North Carolina Standard of Raleigh, a leading Democratic newspaper in the state. The article recommended that those with "black Republican opinions" at schools and seminaries in the state be driven out, apparently suggesting that Hedrick be dismissed. Against much advice, he published a defense in the Standard, explaining his opposition to slavery and likening his beliefs to those of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Subsequently the university faculty passed resolutions denouncing Hedrick's political views, and on 11 October the executive committee of the board of trustees formally approved the faculty's action, which in reality was a dismissal. Meanwhile, the state newspapers were generally unsympathetic to Hedrick's case. On 21 October, while he was attending an educational convention in Salisbury, an unsuccessful attempt was made to tar and feather him. He soon left for the North, where he remained except for visits south in January 1857 and in 1865.

For a time Hedrick lived in New York, where he was employed as a chemist and then as a clerk in the mayor's office. He also did some lecturing and teaching at such institutions as Cooper Union. His services in the mayor's office were terminated after 1 Jan. 1860. In 1861 he went to Washington, D.C., to seek a job with the newly elected Republican government. There he was successively appointed assistant examiner, examiner, and chief examiner in the Chemical Department of the U.S. Patent Office, remaining with that agency until his death.

In 1865 Hedrick attempted to secure a speedy restoration of North Carolina to the Union. He failed to convince state leaders that they should agree to Black suffrage because it would certainly be demanded by Congress. He also strongly advised a policy of moderation in the development of the Republican party and placing governance of the state in the hands of the ablest men. Evidently, he was well acquainted with both President Andrew Johnson and Governor Jonathan Worth. In April 1865 Hedrick petitioned the president for permission to visit North Carolina. Afterwards H. M. Pierce appointed him an agent of the American Union Commission to ascertain the condition of refugees and the poor in the South, paying particular attention to the schools. In 1867 Hedrick was nominated as a delegate to the North Carolina constitutional convention but was defeated in the election. From 1872 to 1876 he was professor of chemistry and toxicology at the University of Georgetown.

Hedrick married Mary Ellen Thompson, daughter of William Thompson, on 3 June 1852 in Orange County. They had four daughters and four sons, one of whom, Charles, J., became a patent lawyer in Washington, D.C. Hedrick died there.