Anti-Slavery Movement in North Carolina

by Rebecca Graham Lasley

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2008; Revised by NC Government & Heritage Library, May 2022

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Appearances can be deceiving. At first glance, the wagon pictured to the right looks like an ordinary farm vehicle of the early 1800s. It consists of a simple wooden box mounted on wheels that are rimmed with iron tires. A single plank of wood serves as the driver’s seat. But upon closer inspection, this wagon turns out not to be so ordinary, after all. Boards in its front and back slide easily out of their slots to reveal a secret compartment. What could a farmer in early 1800s North Carolina need to hide?

Appearances can be deceiving. At first glance, the wagon pictured to the right looks like an ordinary farm vehicle of the early 1800s. It consists of a simple wooden box mounted on wheels that are rimmed with iron tires. A single plank of wood serves as the driver’s seat. But upon closer inspection, this wagon turns out not to be so ordinary, after all. Boards in its front and back slide easily out of their slots to reveal a secret compartment. What could a farmer in early 1800s North Carolina need to hide?

Some farmers of that time might be concealing precious cargo indeed: enslaved people in search of freedom. On their own or with help, many enslaved people escaped or tried to escape to states that did not allow slavery. Local networks (groups of volunteers) sometimes helped them. The term Underground Railroad described these efforts, because the networks operated in secret and helped move people from place to place. Some networks came up with their own vocabulary, referring to the participating locations as “stations,” the vehicles as “trains,” the drivers as “conductors,” and the freedom seekers as “precious cargo.”

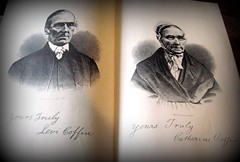

Today few people know the story of the antislavery movement in North Carolina, even though one of the era’s most famous activists came from the state. Levi Coffin (1798–1877)—who became known as “the President of the Underground Railroad” for his determined and vocal campaign against slavery—grew up in the New Garden Quaker community of Guilford County. Although Quakers—members of the Religious Society of Friends, a Christian group—opposed slavery, people disagreed over the best way to express that opposition and help those who were enslaved. Helping freedom seekers was a criminal act with severe penalties. Many Quakers drew the line at breaking the law.

Some Quakers, especially those with more radical views, left the Tar Heel State during the early 1800s, as political conflict over slavery grew more heated. Coffin moved to Indiana in 1826. Among those who stayed behind, Abigail and Joshua Stanley made their home in the Centre Community of southern Guilford County, a station on the Underground Railroad. The Stanleys were the original owners of the false-bottomed wagon. Their young foster sons, Andrew Murrow and Isaac Stanley, served as drivers. We don’t know how many times the wagon made its dangerous, suspenseful journey to Ohio. We don’t know the names or numbers of people who hid inside its cramped secret space. What little we do know of the wagon’s history comes through family stories passed down by Joshua Edgar Murrow. He grew up listening to the tales told by his grandfather, Andrew.

You can see the wagon in Jamestown at Mendenhall Plantation, a Quaker homeplace built in 1811 that is now preserved as a museum. Since the Mendenhall family participated in various antislavery activities, the wagon’s owners decided the house would be a good place for this artifact.

Historical research tells us that, by far, most people who escaped slavery made their way on their own two feet. Although wagons such as this one must have been fairly rare, they have become significant symbols—and reminders—of those difficult but important journeys. At its present location, the wagon prompts many thoughtful conversations among visitors about conscience and courage, as well as thornier topics such as slavery and race relations. In that way, you might say the wagon still serves its purpose, carrying us to freedom.

Educator Resources:

Carolina K12: American Abolitionists, Grade 8. https://k12database.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2012/04/American...

Additional Resources:

DocSouth: Anti-Slavery Movement Presentation. www.lib.unc.edu/dc/ncmaps/abolitionists_k12.ppt

ANCHOR: Quakers and the Anti-Slavery Movement: https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/quakers-and-anti-slavery

ANCHOR: Antislavery Feeling in the Mountains: https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/antislavery-feeling

USHISTORY.ORG. American Anti-Slavery and Civil Rights Movement. http://www.ushistory.org/more/timeline.htm

Archive.org. Bassett, John Spencer. Anti-Slavery Leaders of North Carolina (1998). https://archive.org/details/antislaverylead01bassgoog

The Underground Railroad in Piedmont North Carolina. http://randolphhistory.wordpress.com/2010/02/22/piedmont-nc-quakers-and-...

Wilmington, Abolition and the Underground Railroad: http://www.cfhi.net/TheUndergroundRailroadandWilmington.php

VisitNC: The Freedom Seekers Trail. www.visitnc.com/itineraries/download/the-freedom-seeker-s-trail

Image credit:

Feliz, Elyce. Levi and Catherine Coffin. Photograph. Flickr. November 16, 2011. Accessed Mar. 20, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/elycefeliz/6354200867/

Ditzy Chic. Mendenhall Plantation DSC_0138. Photograph. Flickr. May 7, 2008. Accessed Mar. 20, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/ditzychic/2475121247/.

Mendenhall Homeplace. False-bottom Wagon. Photograph. Mendenhall Plantation, Jamestown, NC. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://mendenhallhomeplace.com/.

1 January 2008 | Lasley, Rebecca Graham