21 Aug. 1863–27 Jan. 1942

[Robert] Heriot Clarkson, civic leader and associate justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, was born in Kingville, Richland County, S.C. His father, William Clarkson, was an officer in the Confederate Army and, after the war, a conductor for many years with the Southern Railway. His mother, Margaret Susan Simons Clarkson of Charleston, S.C., was of Huguenot descent. William and Margaret Clarkson had eleven children, nine of whom survived childhood.

William Clarkson and his family lived in Eastover, S.C., for several years during the Civil War and Reconstruction and moved from there to Charlotte in 1873. Young Heriot attended the Carolina Military Institute in Charlotte from 1873 until 1880, at which time he became a clerk with the legal firm of Jones and Johnston. He studied law at The University of North Carolina for nine months in 1884 and in October of that year was licensed by the state supreme court. He subsequently returned to Charlotte, where between 1888 and 1913 he practiced law in partnership with Charles H. Duls. In 1904, Governor Charles B. Aycock appointed Clarkson solicitor for the twelfth district, a position he retained until 1910. When Duls was selected for a superior court judgeship in 1913, Clarkson formed a partnership with Carol D. Taliaferro. In 1918, Clarkson's son, Francis Osborne, joined the firm.

Active throughout his adult life in political and civic affairs, Clarkson, a Democrat, first held public office in 1887–89 as alderman and vice-mayor of Charlotte, positions he again held in 1891–93. In 1896 he helped to organize a local white supremacy club, one of the many such organizations to appear in the state in the late 1890s. Defeated in 1896 by the Fusion candidate for a seat in the state house of representatives, he ran again in 1898 and was elected. As a member of the house he favored the proposed constitutional amendment disfranchising the blacks of the state; in 1900 he was active on the local level in behalf of the Democratic party's white supremacy campaign.

A dedicated and lifelong prohibitionist, Clarkson was one of the leaders of the movement to ban the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages in North Carolina. He was chairman of the local anti-saloon organization when Charlotte, following a referendum campaign, voted in 1904 to prohibit the sale of liquor. As president of the North Carolina Anti-Saloon League, Clarkson played a vital role in the enactment and subsequent approval in a state-wide referendum of the 1908 act banning the manufacture and sale of liquor. North Carolina, wrote the historian of the prohibition movement in the state, thus became "the first state to adopt prohibition by direct vote of the people." In 1923, Clarkson wrote the Turlington Act revising the state statutes to make them conform to the national prohibition law. Although a spokesman of the dry forces in the state, Clarkson, by this time an associate justice of the state supreme court, supported in 1928 the presidential candidacy of Alfred E. Smith, a critic of prohibition. In 1933 he was among those instrumental in organizing the dry forces in North Carolina to fight repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment.

Although a less significant figure in the good roads movement than in the prohibition crusade, Clarkson nonetheless made important contributions to highway development in the state. He was legal adviser to the Wilmington-Charlotte-Asheville Highway Association, established in 1918, and was active in the Citizens Highway Association, a more or less ad hoc group organized in 1920 to press for immediate enactment of a comprehensive state road law. As chairman of a legislative committee representing the various good roads organizations in North Carolina, he was largely responsible for drafting a proposed bill that, as modified by the General Assembly, became the Highway Act of 1921. This historic measure provided for a $50 million highway expansion program, to be financed through the sale of state bonds.

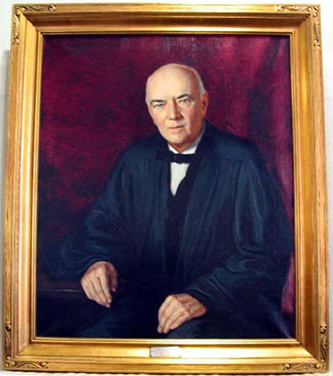

Having served in 1920 as manager of Cameron Morrison's successful campaign for the governorship, Clarkson in 1923 was rewarded by the governor, a close personal friend, with an interim appointment as associate justice of the supreme court. In 1924 he was elected to serve out the remaining two years of his predecessor's original term. He was reelected in 1926 and 1934 for full terms and by the time of his death was the senior associate justice of the court. As a supreme court justice, he rendered decisions upholding the state liquor laws, the "separate but equal" doctrine, and the right of laboring men to join unions. Forty-seven of his opinions appeared in American Law Reports.

An extraordinarily civic-minded person, Clarkson devoted much of his time during his long and useful life to worthy causes. He helped to found both the Crittenton Home in Charlotte and the Mecklenburg County Industrial Home. Over a period of years he sought unsuccessfully to persuade the General Assembly to establish a state-supported reformatory for black boys. Throughout his adulthood, he was active in the Episcopal church and the YMCA, serving from 1935 until his death as president of the Interstate YMCA of the Carolinas. For nearly twenty years (1923–42) he was a member of the North Carolina Historical Commission.

Clarkson was married on 10 Dec. 1889 to Mary Lloyd Osborne, the daughter of the Reverend Edwin A. Osborne. The couple had nine children, five of whom survived childhood: Heriot, Jr., Francis Osborne, Edwin Osborne, Thomas Simons, and Margaret Fullarton (Mrs. John Garland Pollard, Jr.). Clarkson died in Charlotte and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery.