See also: Jugtown; Pottery birthplace, Seagrove area

North Carolina's internationally renowned pottery tradition reaches back centuries-to the time native inhabitants formed local clay into functional pots and ceremonial vessels. Archaeologists have documented nearly complete pots crafted by Cherokee and other native makers that date from the early 1500s. Later, as Europeans settled the region in the eighteenth century, folk potters satisfied the demand of local people who could not afford or had no access to imported ceramics. Adapting techniques from their native England, Germany, and elsewhere, these potters took local clay, glazed their pieces with lead, wood ash, or salt, and fired them in wooden kilns to produce functional vessels for daily use.

Specific characteristics and methods evolved among North Carolina potters in various parts of the state. Through the nineteenth century, although functional use of folk pottery declined, the state's master potters continued to practice and refine their craft, passing it to subsequent generations. In time, folklorists, collectors, and others came to appreciate the distinctive forms of North Carolina pottery as artistic expressions. Potters once again adapted, producing wares to meet this new demand. In the second half of the twentieth century, rising interest in the folk arts helped reinvigorate the potter's craft, prompting contemporary potters to expand traditional techniques and forms in yet other new directions. Today, North Carolina pottery is among the most highly prized in the world. As Chatham County potter Mark Hewitt has written, "As theater is to Broadway, pottery is a treasured manifestation of North Carolina."

Among North Carolina folk potters, three principal regions of pottery production are generally recognized: the eastern Piedmont (Chatham County and the Seagrove area of Randolph, Moore, and Montgomery Counties), the Catawba Valley (Catawba, Lincoln, and Union Counties), and Buncombe County. Potters in these regions produced both earthenware (pieces made of clay with a high content of impurities, fired at a relatively low temperature) and stoneware (pieces made of higher-quality clay, fired at much higher temperatures for greater durability). But in each region, the backgrounds and traditions of potters who settled and worked there influenced the evolution of their wares. The availability of local clays and materials for glazes also helped create regional variations.

The primary earthenware period in North Carolina lasted from the 1750s to the 1840s, slightly longer than in most northern states. A later production period compared to that of the North is due largely to later settlement patterns, a less-developed trade network, and the slower introduction of technological advancements. As a vessel, earthenware exhibits brittle and porous characteristics; it was often coated on the interior or around handles with a dull, lustrous, lead-based glaze ranging from browns and oranges to green-blues. The danger of lead glazing was widely known in the Northeast by the third quarter of the eighteenth century. However, North Carolina potters fired with lead glazes up to the mid-nineteenth century and even use some for nonutilitarian pieces today.

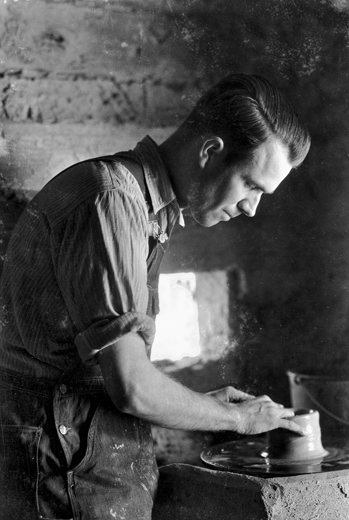

Moravians produced some of the earliest earthenware in North Carolina. Folk potters ordinarily worked part-time with clay, training and employing predominantly male family members and neighbors to make pottery. Traditional gender roles combined with the strength necessary to turn a 5-, 10-, or 20-gallon jar or jug called for male potters. Women occasionally turned smaller pieces, helped with glazing, and performed other chores in pottery production. The familial method of teaching helps explain the over 200-year continuous tradition and multiple generations of folk potter families in the state.

The successor to earthenware was the more durable and vitreous stoneware. The earliest verifiable stoneware producer in North Carolina was Gurdon Robins & Co., established in Fayetteville by 1820. Edward Webster, a member of a prominent family of potters from Hartford, Conn., later operated the pottery under his own name. His brothers, Timothy and Chester, also helped and later moved the pottery to Randolph County, a primary location of stoneware production today. E. A. Poe & Co. in Fayetteville in 1880 typified another North Carolina pottery method. For Poe, a large brickmaking operation, pottery was a side venture, as was common throughout the United States. Unlike Gurdon Robins, who had to import some of his potters in 1820, Poe used North Carolina turners, chiefly William Henry Hancock, who had worked with J. Dorris Craven, and Manley William Owen, from northern Moore County.

Folk potters primarily focused on practical shapes such as jugs, churns, crocks, bowls, pipes, pitchers, and pots of all kinds. Nineteenth-century vessels usually had little decoration, and potters rarely signed their work. Distinctive coggle marks, size inscriptions, handle attachments, general shapes, and other subtle decorative characteristics can identify nineteenth-century pieces. By contrast, early twentieth-century potters embraced the arts and crafts movement in response to customer demand. They discovered a new range of colors and were more explorative with forms. In North Carolina, whimsical pieces such as face jugs or ugly jugs are almost purely twentieth century in popularity. Face jugs show influences from African, German, English, and American Indian precedents.

Well-known potters in western North Carolina in the early twentieth century included Hilton Pottery, Pisgah Forest Pottery, Omar Khayyam Pottery, and Brown's Pottery. The Hiltons produced one of the first pottery catalogs in North Carolina around 1920. Walter Benjamin Stephens at Pisgah Forest became famous for his Wedgwood-style pots depicting frontier scenes in cameo relief. Oscar Louis Bachelder explored unique forms derived from the art pottery movement. The Brown family produced utilitarian ware, which Charles Brown continued to make in the early 2000s. In 1925 Davis and Javan Brown turned one of the largest pots ever made in North Carolina. The six-foot-tall vase remains on display at Brown's Pottery in Arden.

In contrast to selling pottery from a shop or hauling pots by wagon to customers, J. B. Cole, C. C. Cole, A. R. Cole, Rainbow, and North State Potteries made North Carolina's Seagrove area (near Asheboro) known throughout the eastern United States by publishing catalogs of their wares. Pottery catalogs offered customers a chance to select wares without visiting the shop. The Coles received some of their inspiration from the most famous shop in the state, Jugtown Pottery, opened by Jacques and Juliana Busbee in 1921. The Busbees hired local potters Charlie Teague and Ben Owen to turn wares, which were sold locally as well as shipped to Juliana's Village Shop in New York's Greenwich Village. In the early twenty-first century, descendants of the Cole, Teague, and Owen families and Jugtown Pottery continued to produce traditional folk pottery in the Seagrove area and around the state.

The growing interest in traditional arts and crafts that encouraged folk potters of European descent to advertise their wares in catalogs and experiment with new forms and methods also influenced the state's Native American potters, particularly among the Cherokee. While European potters typically turned their pieces on wheels and fired them in closed kilns, Cherokee potters traditionally manufactured coil and pinch pots by hand and, it is believed, fired them in open pits of wood coals. Until the late nineteenth century, native potters concentrated on producing earthenware for their own use, including large jars for hominy and a variety of smaller cooking pots and vessels. These pots were not glazed like European earthenware or stoneware; rather, they were sealed with soot from burned corncobs that allowed the vessels to hold liquids. Some were stamped with paddles, producing a distinctive design.

By the twentieth century, Cherokee and other native potters in the state found an emerging tourist market for their work, prompting many to produce more polished pieces. As anthropologists and other scholars worked with Cherokee potters and recovered older pieces that could serve as models, however, interest in returning to traditional forms and methods grew as part of a larger Native American cultural renaissance in the late twentieth century. Today, such work can be seen and purchased at such locations as the Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual and the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee.

In the early 2000s more than 2,000 potters were active statewide, creating forms of all types-from eighteenth century traditional shapes and modern utilitarian ware to abstract wall-mounted sculptures. Only a handful of turners created pots in the "traditional folk manner." In the Seagrove area, more than 70 pottery shops produced wares on a small commercial scale. A few traditional folk potters were working in Lincoln County near Charlotte and in Buncombe County near Asheville. Many turners adhered to forms produced in North Carolina for over 80 years. Some potters strived to develop unique shapes and glazes. The majority, however, as exemplified by potters such as Burlon B. Craig, Vernon Owens, Ben Owen III, Charles Brown, and Bob Armfield, were combining the turning arts of the past with fresh perspectives, enriching the storied folk pottery tradition in North Carolina.