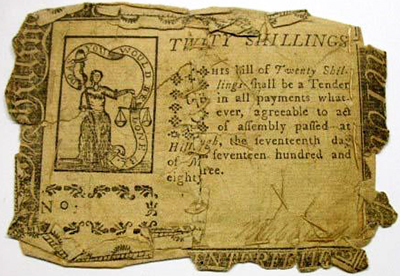

The British encouraged the counterfeiting of Continental money during the Revolutionary War to weaken the American war effort. A 1779 law passed by the General Assembly criminalized the reproduction of currency or lottery tickets issued by the Continental Congress or any other state. It also imposed up to a year's imprisonment and branding of the letter C on the left cheek of the offender, in addition to the required flogging and pillory time for a first offense.

During the Civil War, Confederate money circulated in North Carolina to replace U.S. coinage. Counterfeiters were particularly active during this time, especially in the early years of the war before inflation destroyed the value of Confederate currency. North Carolina's newspapers often warned the public about new counterfeit notes and advised readers how to detect them. Some forgeries were skillfully made, but others were evidently quite amateurish. In 1863 a batch of bogus three-dollar notes quickly aroused suspicion, as the state was not issuing three-dollar bills at that time.

Many counterfeiters altered genuine notes by pasting numbers clipped from worthless older notes onto new bills to raise their value. In 1862 forgers in Raleigh used this method to transform a number of 2-dollar state bills into 10-dollar notes. Other bills were altered with a pencil, such as a batch of 5-cent notes that were changed to 50-cent notes and circulated in Wilmington.

The National Bank Act of 1863 made the federal government the sole source of U.S. currency and prohibited states, banks, and businesses from issuing their own money. Although laws against counterfeiting remained on the books in North Carolina, detecting and punishing such forgers became a federal matter.