12 Sept. 1851–26 Dec. 1922

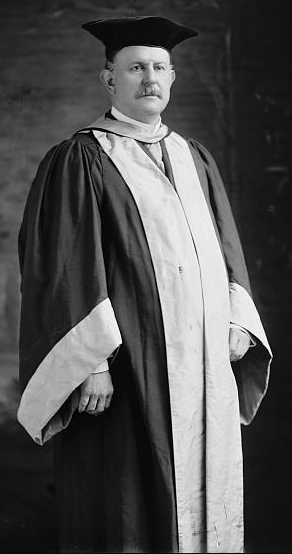

Hannis Taylor, lawyer, scholar, and diplomat, was born in New Bern, the son of Susan Stevenson and Richard Nixon Taylor, a merchant. He was the grandson of Mary Hannis and William Taylor, Scottish immigrants, and of Elizabeth Sears and James C. Stevenson of New Bern.

Young Taylor had just completed a classical elementary education at New Bern Academy when civil war came to the North Carolina sound region. In March 1862 he and his family fled inland to Chapel Hill, where they were safe from Union troops. There Taylor continued his studies during the years 1862–65 with Cornelia Phillips Spencer and in 1865 with Dr. Alexander Wilson. After the family moved to Raleigh in 1866, Hannis completed his preparatory studies at Lovejoy's School (1866–67) and then entered The University of North Carolina in July 1867, but family financial straits forced him to withdraw after nine months of study. He returned with the family to New Bern and there, with his ambition fixed on a legal career, served as a law clerk under John N. Washington. When Washington died in 1869 and tuberculosis began to claim many lives in the New Bern area, Taylor's parents decided to move to Point Clear, Ala., where the father hoped to obtain work in the production of naval stores. Shortly after arriving, Taylor's mother died, and as a result his father seemed unable to function. In December 1870 Hannis moved the family—the father, four brothers, and two sisters—across the bay to Mobile and thus became head of a household at age twenty.

In Mobile, Taylor worked as a law clerk on a modest salary before gaining admittance to the Alabama bar in 1872. With credentials to practice, he first served as solicitor of neighboring Baldwin County but within a year had turned to private practice. As a man of legal and public activities in Alabama, he gained a regional reputation for his avid, if fruitless, attacks on the federal antilottery law (Ex parte Rapier, 143 U.S. 93–103) and for his advocacy of industrialism and other New South programs. He rewrote the Mobile city charter in a way that kept the city from being liable for its Reconstruction debts. Soon he had a name in international scholarship circles as the Alabamian who wrote Origin and Growth of the English Constitution (2 vols., 1889, 1898), for which the University of Edinburgh honored him with the L.L.D. degree. Because of this work and his association with the conservative branch of the Democratic party, Taylor was chosen president of the Alabama state bar (1891) and, during Grover Cleveland's second administration, was appointed minister to Spain (1893–97). During and after his Madrid tenure, Taylor's strong advocacy of American intervention in Cuba offended the administrations of Grover Cleveland and William McKinley. Even so, Taylor received considerable attention for his expansionist views; when the Spanish-American War was concluded, he attempted to use this reputation to win election to the U.S. House of Representatives from Alabama's First District. He lost in the Democratic primary in 1898 and again in 1900, owing chiefly to his having married Leonora LeBaron, who belonged to a prominent Roman Catholic family in Mobile.

Frustrated over chances for personal advancement in the South, Taylor moved to Washington, D.C., in 1902. He taught part-time in the law school of George Washington University and practiced before the U.S. Supreme Court. More important, he became a Republican publicist, supporting Theodore Roosevelt and his progressivist policies and publishing many articles in the North American Review and other prestigious journals. Taylor also served as special adviser to the Spanish Treaty Claims Commission (1903–10) and as American counsel to the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal (1903). He gave similar support to William Howard Taft but levied constant criticism at Woodrow Wilson, especially regarding Wilson's use of the militia in World War I (Cox v. Wood, 247 U.S. 3–7). Soon after failing to win an appointment in Warren G. Harding's administration, Taylor died of Bright's disease. He had become a Roman Catholic nine years earlier. He was buried at Fort Lincoln Cemetery in Maryland but very near Washington. Surviving him were his wife, three sons—Alfred R., Hannis Joseph, and Charles LeBaron—and two daughters, Mary L. T. Hunt and Hannah T. Bayly.

Aside from some one hundred articles and The English Constitution, Taylor's major writings include A Treatise on International Public Law (1901); Jurisdiction and Procedure of the Supreme Court (1905); The Science of Jurisprudence (1908), which Oliver Wendell Holmes castigated for its plagiarism; The Origin and Growth of the American Constitution (1911), advancing the strange thesis that Pelatiah Webster was the architect of the U.S. Constitution; and Due Process of Law (1917).